"In the metabolism of the Western world, the coal miner is second in importance only to the man who ploughs the soil."

George Orwell, Road to Wigan Pier

Introduction

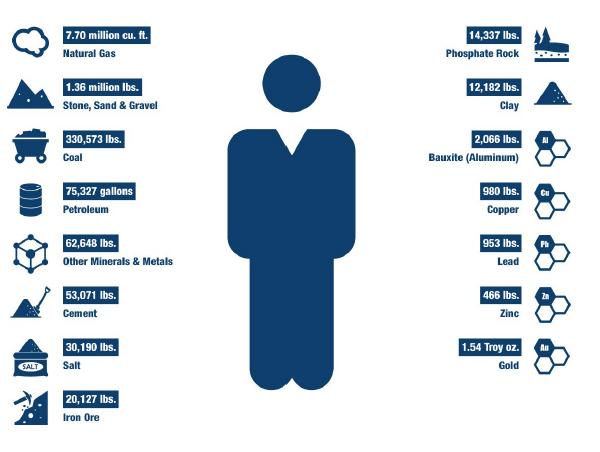

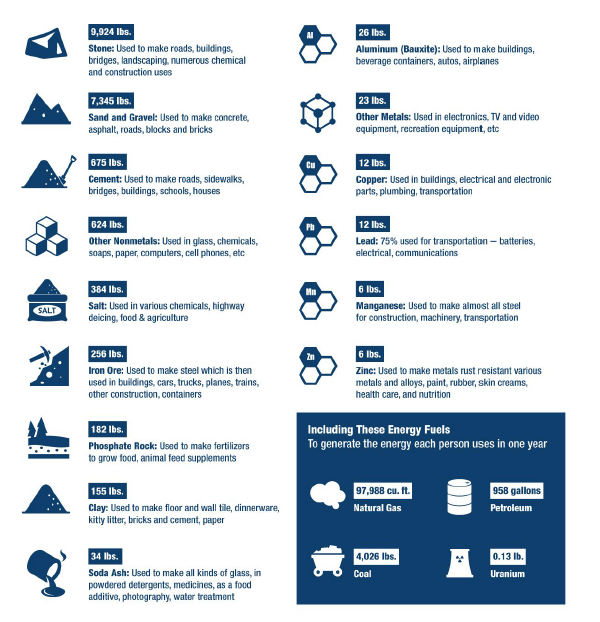

Mining is the material basis for life: mankind now depends on at least 90 metals and mineral commodities to power and charge the global economy.1 According to research by the Minerals Education Coalition, it is assumed that every American born will need 3.19 million pounds of minerals, metals and fuels in their lifetime (Figure 1). Every year, 40,633 pounds of new minerals must be provided for every person in the US to make things that are used daily (Figure 2).

Figure 1. An American’s Needs

Source: Minerals Education Coalition2; as of 2019.

Figure 2. New Minerals Needed Every Year for One Individual in the US

Source: Minerals Education Coalition3; as of 2019.

However, mining is bad for the environment – there is no way around it. Environmental impacts caused by mining could include deforestation, relocation of communities, diverting rivers if a dam is needed for power purposes – the list goes on and on. Indeed, it is hard to identify a part of the world where resource extraction is expanding without conflict.

For responsible investors, then, this poses a dilemma: should mining companies be on an exclusion list? Or should there be engagement with mining companies to make them more ‘responsible’? Where does a responsible investor draw the line as to what constitutes ‘bad’ or ‘good’ mining company that they should not, or should, invest in? Are these the same principles that are followed regardless of whether you are investing for a responsible investment-focused fund or a pure mining-focused fund?

At Man Group, we are asking these exact questions. The transcript below is from a roundtable discussion held with Jason Mitchell, co-head of responsible investment; Mark Ashton, a portfolio manager focused on the mining sector; and Michael Canfield and Louis Rieu, co-portfolio managers focused on responsible investment.

Bluntly, the practicalities of mining are unethical – in terms of ecological destruction, pollution, employee safety, land conflict, etc. Should we just accept that mining is unethical, but necessary?

Mark Ashton (MA): It ultimately comes down to demand. Mining is going to have to exist: to have a green economy, we will need certain metals such as copper, nickel, cobalt, aluminium, lithium, etc. So, while there are nuances within the debate, we believe it is the responsibility of the mining companies to operate in the most ethical manner possible, and to be held accountable. From a company’s standpoint, the ‘licence to operate’ is the most important factor: ensuring the sustainability and safety of operations means that a company can continue to operate; without this, it doesn’t have a business. I think this is a fundamental point often overlooked by the investment community.

Jason Mitchell (JM): I wouldn’t start from the point of ethics. There is just no global consensus on this issue. You might make an argument that mining thermal coal is bad, but there is just no consensus that says that diamond mining is bad, for instance. The Paris Agreement carries specific implications for coal, namely a quick phase-out of thermal coal to stay in line with a 1.5C temperature limit. It’s worth recognising explicitly that the nature of mining, whether it is across supply chains or the fact that it often occurs in developing countries, make mining inherently prone to more environmental, social and governance (‘ESG’) issues than other areas.

Michael Canfield (MC): If you are still producing smartphones, cars, train tracks or planes, mining is unavoidable. I’d take issue with the notion of describing a mining company as ‘bad’ per se. For us, the question is how you define it. When we analyse the sector, materiality is the most important ESG consideration. It is the ‘E’ pillar – the environmental impact — of ESG that we see as the most critical starting point for discussion. Be it treatment of hazardous substances, tailings management, water usage, greenhouse gas emissions or recycling targets, these considerations are key to our analysis of a company’s ESG credentials. Socially speaking, it is the company’s social license to operate, its employee health and safety performance/programmes and its human rights policies that we are most concerned with. Finally, from a governance perspective, the considerations are similar to other sectors, ranging from bribery or corruption policies and business ethics to management incentivisation, etc.

Louis Rieu (LR): To directly answer your question: No, I don’t think we should. Whilst most would agree that mining is necessary, and has many positive attributes, the idea that anything should be given ethical free reign is wrong. Ultimately, everything we do carries a cost, and we have to ensure the cost is worth it. With respect to mining, I believe that the costs associated with the ‘E’ and the ‘S’ of ESG, specifically, are underappreciated.

So mining is necessary, but it has negative impacts. As such, what framework can one use for evaluating the trade-offs between the two?

MC: From an ESG perspective, everything has to come back to ‘net’, as in the ‘net benefit’ of any action should be positive. For instance, look at electric cars. The car’s carbon emissions may be minimal once it is on the road, but what about on a full lifecycle basis? If the environmental cost of manufacturing the vehicle (e.g. extracting the rare-earth elements needed for current battery technology) were to be more destructive than building and running a standard car, is it worth it? The Union of Concerned Scientists suggests emissions from longer-range electric vehicles (more than 250 miles per charge) could have as much as 68% higher manufacturing emissions vs a gasoline vehicle.4 Once the car is on the road, the Department of Energy estimates that a Tesla Model S consumes as much energy in 20 miles of driving as it takes to produce a gallon of gasoline.5 We are not arguing that electric cars are net ‘bad’, but simply highlighting that the environmental debate is not so clear-cut.

LR: It comes down to information. The more accurate information we have on the whole process, the better the decisions we will make as to whether something is worthwhile. I think of this process in two layers. Firstly, there has to be some form of regulatory oversight. Regulators have a duty to remain one step ahead to ensure that companies’ activities do not cost society as a whole more than they contribute. Fortunately, we don’t have to rely on this. Within the second layer, the key decision makers are corporates, capital and consumers. Companies are fundamentally capitalist and should be free to operate within regulations, but as the awareness of, say, environmental concerns becomes more widespread, the company-consumer feedback loop means that profits will be driven to companies who operate ethically. This will clearly draw in capital, and we can see this already happening in the markets.

JM: There are two challenges to building a universal framework: exposure to developing countries and regions in conflict. For instance, Man Group doesn’t invest in conflict zones, but many corporates do operate in areas which are considered ‘dicey’. This can create a situation, which also would have an analogy in thermal coal: if a listed company sells these assets, transparency plummets and it becomes really hard to know if people are operating responsibly. Think about it in a listed context – in Australia, investors have rallied to sell or divest thermal coal. But if you sell it to a company that does not have the same transparency requirements, engagement opportunities and accountability as a listed company, that’s arguably worse than holding the asset on your own books, where there is no scrutiny.

MA: We have seen a trend in listed mining companies divesting thermal coal assets (for example, Rio Tinto, South32). Thermal coal generally occupies a small part of the asset base, and with little incentive to invest new capital, the decision to divest versus invest is generally considered to be an easy one by the investment community. However, to Jason’s point, the decision to divest is not simply about realising a net present value outcome. There are also considerations around the ESG track record of the potential acquirers and whether the assets will continue to be operated to a high standard and with transparency. It’s worth pointing out that listed coal companies tend to trade on cheaper multiples than other industrial mining companies. It’s interesting to see this development being reflected in prices, and it could be cited as an example of the market being efficient with respect to ESG considerations. In terms of the decision to not invest in coal assets, there are other factors to consider – many communities rely on coal mining; and in the event of a mine closure, ensuring sustainable transition, decommissioning and rehabilitation of the mine site. There are multiple dimensions to the issue and therefore the decision to divest versus invest may not always be straightforward.

MC: From a cost of capital standpoint, a number of European banks (including Credit Agricole, Natixis, Commerzbank, ING, RBS, Lloyds), have policies precluding financing of new thermal coal projects. As this trend proliferates, it will become harder and harder for the sector to operate profitably. Returning to the framework, regulation is undeniably getting stricter. The most extreme version we could have, eventually, would be a requirement for companies to track and disclose exactly where they source their raw materials from down to specific mines. One example of a company making strides forward in more sustainable raw material sourcing is Apple. Enclosures for the new MacBook Air and Mac mini computers use a new alloy engineered by the company so they can contain 100% recycled aluminium. The company has also eliminated beryllium, mercury and several other harmful chemicals from its product range.

There are a lot of codes, covenants, and standards when it comes to mining: the International Cyanide Management Code, the Equator Principles, the International Finance Corporation’s Performance Standards, the Global Reporting Initiative, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, the Natural Resource Charter and the United Nations’ “Ruggie Principles,” to name just a few. However, these are all voluntary and self-enforced. Would an internationally enforced standard help?

MC: This goes back to the point about developed versus developing countries. There are countries that rely on dirtier commodities for power generation, amongst other things. World Bank data suggests that in 2015, four countries (Kosovo, Botswana, Mongolia and South Africa) all depended on coal sources for more than 90% of their electricity generation needs.6 This compares to 2.2% for France in the same year. Such discrepancies make a globally-enforced standard on commodity use very complicated and arguably unfair. I’m not saying that it shouldn’t exist, but the reality is that the practicalities of enforcing such a policy would be immensely challenging. The picture would be further complicated by nations in conflict. In principle, however, a globally agreed set of standards for mining makes sense. They exist for other industries (such as the UN PRI for finance), so why not for mining?

MA: The London Metal Exchange, for example, has launched a responsible sourcing requirement.7 For some commodities, such as cobalt, there are ESG issues with activities such as artisanal mining in places like the Democratic Republic of Congo, which the framework is designed to address. Norsk Hydro, for example, is looking at producing and marketing low-carbon aluminium. Will these ‘greener’ products lead to premium pricing outcomes and hence further incentivise companies to invest and innovate?

LR: Responsible investors have certain expectations of listed companies. It could be possible to get to a point where we have a TCFD-style set of standards and behaviours required of listed mining companies. Can we get to a point where we have a strict, global set of rules across all companies, public and private? Probably not. Ultimately, who will police it and how?

JM: One area of progress has been the renewed demand for a global standard for tailings management, which has directly stemmed from the Brumadinho disaster in Brazil. We now have had an independent Global Tailings Review led by former Swiss environment minister, Professor Bruno Oberle, and jointly convened by industry and investors through the International Council on Mining and Metals, United Nations Environment Programme and Principles for Responsible Investment. The result has been the launch of launch a new public global database of around 1,800 tailings dams. There is still some way to go, since there are as many as 33,000 in existence globally, which all need to be tracked. Nevertheless, this does represent progress for the industry, even if it has come after such a tragedy.

Mining is an industry with a historically poor safety record, but one which is inherently more dangerous than other industries. Many companies are aware of this, laying out their non-financial key performance indicators (‘KPIs’) in their annual report, of which safety is one. But safety issues are often identified in retrospect, and have a short-term costs which isn’t necessarily recouped in profit margins. How do we encourage companies to spend on safety, if the capital expenditure will not necessarily lead to profitability?

MA: I believe safety does get rewarded and is usually the sign of a well-run company. In addition to ensuring employee wellbeing – which is the most important consideration – a company with a good safety record usually has good operating practices, well-capitalised assets and a highly skilled workforce. Employee wellbeing allows companies to not only attract and retain the best people, but can lead to less operational variability and hence more stable earnings. In an inherently volatile sector like mining, this should lead to a premium multiple. Of course, there will always be uncertainties such as geology and weather, but it’s about controlling the controllables and having processes in place for the uncontrollable. A lot of that starts with the culture of a company. Safety is a critical component of a company’s licence to operate: if a company has a bad safety record, they will find it hard to win a tenders, develop new projects and, in some instances, could lead to existing operations being halted.

MC: This is much like the broad ‘quality’ factor argument across all sectors, not just miners. On both ‘S’ and ‘G’ credentials, if you are a ‘better’ company, you ought to trade at a premium valuation multiple versus your peer-group.

JM: There can be warning signs to bad practices; greenwashing can’t be escaped.

So how do we solve greenwashing when investing in mining companies?

MA: The effort to take on greenwashing has to be industry-wide. Targets need to be set and stakeholders need to hold companies accountable; there needs to be increased transparency with information presented in an independent and objective manner. There also has to be sufficient technical capability and resourcing, which requires industry-wide investment.

LR: This is where engagement comes in. Being close to our companies and their peers, it becomes clear who is taking this seriously and who is not. It allows us to have a better view of, and better quantify, the risks involved with an investment.

MC: One solution could be an industry-wide, independent auditor. Specifically on greenwashing, the warning signs for us are, for instance, companies who own some wind farm assets and subsequently claim that are ‘green’ because they derive a small percentage of their energy needs or profitability from renewables. Instead, we need to delve much deeper. Does a company have a team with dedicated knowledge of and accountability for ESG performance? Is one company’s operational practice a standard that should be introduced across the industry? Good behaviour has to be intrinsic within an entire organisation, rather than just a single geography or a single asset. It also has to be led by example from senior management down through the organisation. This is true of the entire listed equity world, not just miners.

Mining communities are usually entirely reliant on the industry: mineral deposits are often the only factor which has encouraged habitation in the area. As we’ve seen from mine closures in the north of England, after mines close, ‘stranded communities’ often face deprivation, poverty and other social problems. What can be done to tackle the issue of ‘stranded communities’? And how can we resolve the conflict between indigenous/ First Nations land use and rights, and the economic imperative for mining?

JM: Under Just Transition, you can link climate with social outcomes. In other words, you can’t advance climate legislation without bringing people onside. When you place climate versus jobs, it forces a political choice. In the most recent Australian election and in the 2016 US Presidential election, people voted for candidates who roughly promoted a ‘jobs’ policy over a ‘climate’ policy. In Germany and Spain, parties who have pitched on a ‘climate’ platform have done better, usually allied to promises of retraining and retirement benefits. The answer to both is effectively government cash transfers – Spain created a EUR250 million fund to support the closure of its coal-mining industry.

MC: To us, this comes down to an argument of ‘one-off’ versus continuous support. The worry with a one-off cash payment is always: does it get wasted, or does it genuinely go back into the community? In contrast, an annuity or profit-share agreement could be regarded as much more stable. The addition of community infrastructure – like schools and hospitals – is a really important indicator that a company is not just throwing money at a community and then ‘washing its hands’. There is a risk that companies could initially underestimate a mine’s worth so as to reduce the payment made to the community. A better approach arguably could be for the company to commit, during a set period, to build an agreed-upon number of schools, hospitals and infrastructure, and to maintain a continuous dialogue with the community even after the end of the life of the mine site. That could be a truly inclusive, sustainable approach.

MA: Exactly! It’s about investing in communities – not just in services, but importantly in education and training, and the development of local businesses that can support the operation and the community for the life of the mine and beyond. There have been debates about ‘fly-in fly-out’ operations. This is where workers would be flown in for their shift and then return to a major capital because it was more economical to do this than develop infrastructure and workforce locally. Of course, at remote sites, this may be necessary. However, this is an example of shorter-term financial decisions versus taking a longer-term sustainable approach.

LR: I think we have to come at this from the point of view of the local community as well. It is easy to agree that they should be informed and empowered to make a decision as to whether they want it or not. Doing so helps ensure that all the associated costs of a project are accurately reflected in the decision to press ahead, and it has to include leaving local communities in a fit state to carry on, something which often gets under-estimated. While this does increase the cost of business for a mining company, and in turn the consumer, this also means, in theory, that the world would only consume what it should.

MC: This does almost bring us back to the regulation discussion. Should there be a global standard around this? Should the community get a pre-determined percentage stake in all mining projects globally? At least in terms of listed companies, it should be feasible to create industry-wide regulations guiding best practice when it comes to community engagement.

LR: True, and there is a risk that this process would favour larger companies, who have the resources, but again the regulatory framework would have to account for this. In reality smaller, less regulated, companies end up taking shortcuts just to be able to compete. This is clearly dangerous, and tells you explicitly that something is wrong with the current set-up.

As ESG responsibilities apply to more and more investors, does this inevitability mean miners will trade at a discount, given the industry has a heavier ESG load than most?

JM: In the tobacco sector, for example, we have seen large investors such as the Australian Supers, divest from the sector completely. This may not be where we’re going with mining, apart from thermal coal, but it is illustrative of what can happen if assets do leave forever.

MA: Obviously mining is going to have a relatively low ESG score when compared to many sectors in the market. But assuming the world will continue to demand certain mined commodities – particularly in the transition to a green economy – the real questions for an investor with a sensible approach to allocating capital should be: which mining company has a sound and proactive ESG strategy? Which company is going up the ESG curve, which one is going down and are the companies investing in technology and process to help them improve? All this is important, rather than just looking at net carbon emissions, for example. As we’ve discussed, mining touches all aspects of ESG; and the challenges and opportunities are multi-dimensional.

MC: We want to invest in ‘leaders’ in the sector and the companies that are driving to be better. This approach works best at inflection points. Of course, one can invest in companies that are already great. However, I believe the real opportunity comes where ‘bad’ companies are trying to get to ‘good’. Fundamentally, it’s not sensible to exclude the entire sector. We don’t live in a perfect world; and we certainly are not at a stage of being in an infinite loop of recycling, with no need for further extraction of resources.

JM: Share prices are also going to reflect the transition risk inherent in mining. As we look to transition to a low-carbon economy, there is a risk of stranded assets for miners, especially those owning thermal coal. It is very possible that the transition risk is a factor why mining companies could trade at a discount to the wider indices.

Does the engage versus divest debate even work with mining companies? Should it?

MC: Engagement is critical, in our opinion. We strongly believe this is how ESG investors can have a positive impact and hold companies accountable over time. Through engagement, you can encourage more companies to reach higher standards. We, as a firm and as fund managers, are critical stakeholders in discussions across all sectors. Companies ultimately have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders, putting us in a privileged position to drive positive change in the world. As a firm and as an industry, we recognise we have a huge responsibility to use our power for good. As a firm with real scale, we have a particularly loud voice to deliver a net positive impact on the world. Divestment sends a signal to companies, but unfortunately, you arguably lose some of the impact if you subsequently try to push the industry towards better behaviours and policies.

LR: Yes, I believe it does. In my mind, it comes back to the wish to be net positive. As investors, we should be allocating capital to companies which we consider to be best in class, as well as those who are trying to improve. If an investor divests its share in a company, it will guarantee that the company will no longer listen to your input. To keep improving the way in which we operate, we need to have a voice at the table when mining companies are making decisions.

1. See “Minerals Yearbook: Volume I—Metals and Minerals,” U.S. Geological Survey; https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/minerals-yearbook-metals-and-minerals.

2. https://mineralseducationcoalition.org/mining-mineral-statistics

3. https://mineralseducationcoalition.org/mining-mineral-statistics

4. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/cleaner-cars-cradle-grave#.Vv0_OhIrKRt

5. https://www.wired.com/2016/03/teslas-electric-cars-might-not-green-think

6. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.COAL.ZS?most_recent_value_desc=true

7. https://www.lme.com/News/Press-room/Press-releases/Press-releases/2018/10/LME-proposes-requirements-for-the-responsible-sourcing-of-metal-in-listed-brands

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.