This article was initially published in Forbes

Introduction

“What’s past is prologue,” Shakespeare said in The Tempest. By this, I think he was saying that the past prefigures the future: what comes first determines what comes later.

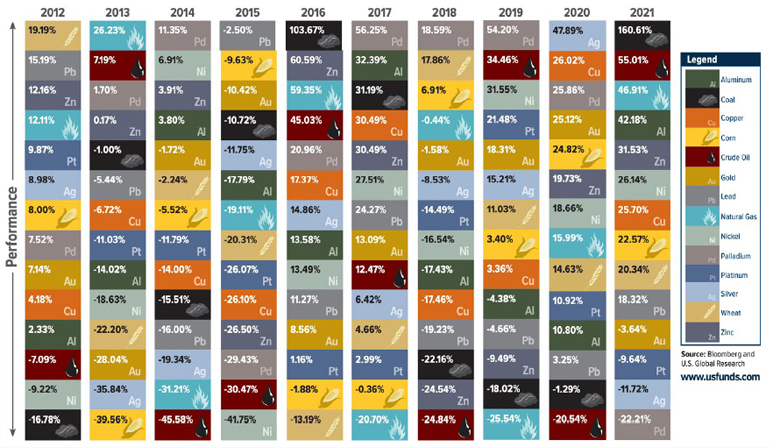

If we apply this maxim to commodity investment, it’s hard to figure out what exactly the past is trying to tell us, at least as far as recent performance goes. Just take a look at ‘The Periodic Table of Commodities Returns’ (Figure 1), put together by US Global Investors.

Figure 1. The Periodic Table of Commodities Returns 2021

Source: Visual Capitalist/US Global Investors.

Pick a commodity and follow its trajectory over the past 10 years. Prices, it is fair to say, have been volatile.

For a dizzying ride, pick a commodity and follow its trajectory over the past 10 years. Prices, it is fair to say, have been volatile. In fact, the best guess for any commodity’s performance has been to look at the previous year and simply expect the opposite. Past returns here are definitively not an indicator of future returns; or, in Shakespeare’s words, the past is anything but prologue. Looking at this chart, the words of the British writer LP Hartley replaced those of Shakespeare in my mind: “the past is a foreign country – they do things differently there.”

So, if not prefigured in their past, what exactly is driving the recent and relentless volatility of commodity prices? It’s something I’ve been discussing with my friend and colleague Ed Cole.

The Price Is Right

When faced with limited supply, prices naturally become more volatile. A sharp increase in demand leads to an outsized jump in price. Consider, for instance, palladium. In 2015, palladium prices fell by 29%, reaching a six-and-a-half year low. Immediately afterwards the Volkswagen emissions scandal hit, and palladium soared. The reputational collapse of the diesel engine had forced drivers back to gasoline and lifted demand for palladium-constructed catalytic converters.

With limited supply to respond, the price rapidly increased, only falling again this year as a global chip shortage reduced demand for cars in general, and new technology made it possible to swap palladium for platinum.

One might wonder how commodities are ever considered a safe harbour for investors. And yet, when inflation strikes, they have traditionally been viewed as precisely that.

So, exposed to the vicissitudes of world events, one might wonder how commodities are ever considered a safe harbour for investors. And yet, when inflation strikes, they have traditionally been viewed as precisely that.

During periods of inflation, commodities have one great advantage. The price of a commodity is a pure representation of the meeting of supply and demand at that moment. The price of copper today represents the value of copper on that day and no other. Equities, on the other hand, are different. Their price contains a prediction about the future. The price of a share in Alphabet today includes a projection of its performance, one that looks increasingly unclear when set against the murky horizon of an inflation-ravaged future. Bonds suffer to an even greater extent during periods of rising prices, with the promise of a long-term fixed income set against the corrosive effect of inflation.

Using past performance to try to predict future prices is likely a loser’s game. The key contributor to the relationship between commodities and US inflation has historically been oil, and one might well ask whether the price of oil is more often a cause of inflation, as it was in the 1970s, than a result of it.

And will the price of oil remain such a dominant component of a global economy that, judged by the rhetoric of its leaders at least, appears to want to use less of the stuff?

Commodities and Climate Change: A Match Made by Necessity

Ed Cole’s argument, which I largely subscribe to, is that the global response to climate change makes the case for commodities stronger, not weaker. Oil supply, after all, is low and will likely remain so. Despite huge cash reserves, energy companies are not investing in what their shareholders consider ‘stranded assets’. Investment in oil and gas supply has decreased gradually since 2014, falling markedly in 2020 to around 40% of 2014’s figure.

At the same time, oil demand is set to rise. Goldman Sachs recently reported that it expects demand to reach record levels, and even floated the possibility of oil prices rising to over USD100 per barrel next year.

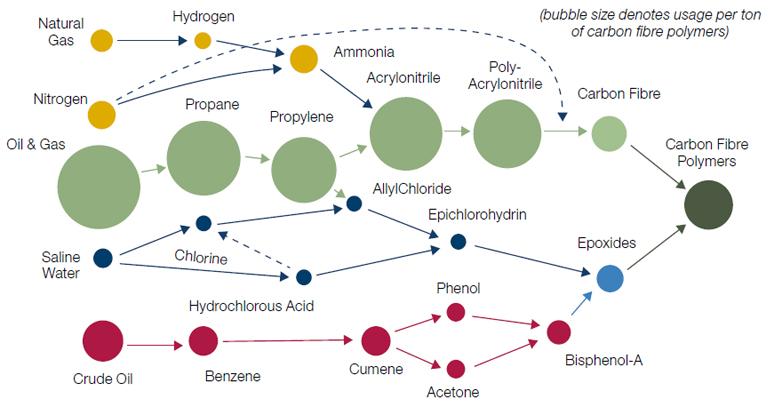

What seems clear is that demand for oil is going nowhere in a hurry. In an excellent Twitter thread, Ed Conway of Sky explained why addressing climate change demands that we do more “dirty things” in the process. The carbon fibre required to build wind turbines was one such example. “The clue is in the name,” Conway points out, alongside an excellent illustration of the complex supply chain that gives the fibre its carbon (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Long and Intensive Supply Chain Behind the ‘Carbon’ in Carbon Fibre

Source: Thunder Said Energy, Via Ed Conway.

An equally complex supply chain leads us to solar panels. Although panels aren’t made from fossil fuels themselves, carbon is vital to their production. Turning quartzite, or silicon dioxide, into metallic silicon requires firing an arc furnace to around 2,000 degrees Celsius. Only one substance can burn at a heat so ferocious: coal – the commodity, you might have noticed, that delivered the highest returns in 2021.

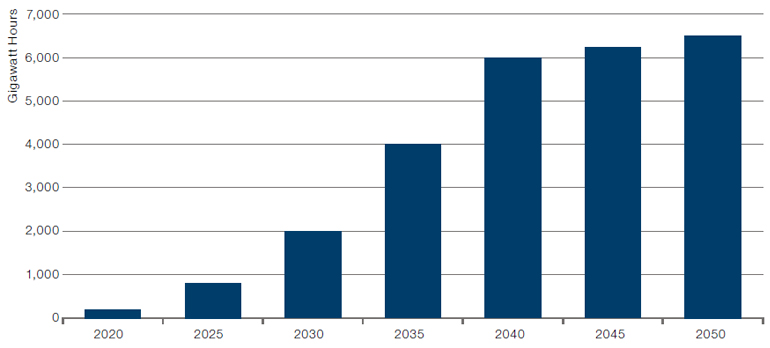

Beyond fossil fuels, investment in climate infrastructure will stimulate demand for a wide number of other commodities, most notably industrial metals. Investment in electric vehicles, battery technology, and in renewable power plants will all stimulate significant demand. Renewable energy systems, for instance, consume five times more copper than traditional approaches, while an electric vehicle consumes 60kg more copper than a car powered by internal combustion.

Supply is already strained by the significant increase in electric vehicles. Writing in the Sunday Times in December, Jon Yeomans quoted one mining investor’s prediction that “the coming boom will dwarf the supercycle in commodities unleashed by China’s rapid growth 20 years ago.”

Figure 3. Forecasted Demand for Electric Vehicle Batteries Worldwide, 2020-2050

Source: The Faraday Institution.

Once again, in pursuit of understanding the future, we are sent back to the past. The key thing to recognise is that we have been living through an exceptional period, one in which many of the tenets underpinning commodity pricing were supervened by the juggernaut of central bank stimulus and liquidity and the rising power of the ESG movement.

Conclusion

Commodities have been a hedge against inflation before, and they could well be again.

If we are now moving into a new inflationary regime, these tenets are likely to reassert themselves. Commodities, which are priced demand against supply with no need to project into the future, lose less of their value to inflation. Fossil fuels meanwhile, both under-supplied and in significant demand, could surge. Meanwhile, green investment will create new demand for industrial metals. Viewed over the past 10 years, commodities hardly appear a safe harbour for investors. But if the last decade was an exception, the longer view might be more instructive. Commodities have been a hedge against inflation before, and they could well be again.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.