Introduction

Utopia, famously, means nowhere. When Thomas More sought to write a satirical book about an imaginary land, he made up a word in ancient Greek: ‘ou’ – not, ‘topos’ – place. Utopia: ‘Not Place’, ‘Nowhere’.

The road to Utopia ultimately leads to nowhere. Instead, investors need to support a pragmatic transition.

As investors, we must deal with the world in its current state. In Europe, the leader of environmental-focused policymaking, we find ourselves requiring ever-larger stocks of coal and other fossil fuels to stave off an impending winter energy crisis. The utopian ideal – a rush towards 100% renewable-powered energy mix – meets the pragmatic reality that we simply do not yet have neither the technology nor infrastructure. Here we have seen the acutest example of the energy dilemma; how can investors, and we as individuals, access energy that is (1) available, (2) affordable, (3) secure, and (4) sustainable. To over-prioritise one would be to jettison the other three, unthinkable for any modern fund manager or policymaker. We need to consistently choose the lesser of two evils, rather than pretending a perfect solution exists; choosing cleaner natural gas or even nuclear over dirtier oil and coal; funding polluting miners that underpin the electrification of the economy; investing in the oil majors who are working to become renewables majors.

The road to Utopia ultimately leads to nowhere. Instead, investors need to support a pragmatic transition.

Four Criteria for an Orderly Transition

The first point to stress is that the need for an energy transition remains as acute as ever. To achieve the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, it is estimated that we need to cut emissions by 45% by 2030 and achieve net zero by 2050. However, the direction of travel has not been quick enough, with most countries behind on their targets.1

The second is that for the target to be achieved, it requires individual consumers to be persuaded to support it. It is no good governments making commitments to curb emissions if their policy decisions actively erode the base of support for pro-environmental policies. For the energy transition to be orderly and effective has to abide to four criteria, ensuring the availability, affordability, security, and sustainability of energy supplies. As we have seen this year, if these criteria are violated, support for pro-environmental policies dries up.

The unpleasant reality is that this scenario requires trade-offs. Until we see major technological breakthroughs, the world’s energy mix remains reliant on fossil fuel exploitation (Figure 1). Furthermore, the section attributable to renewables contains a great deal of embodied carbon in its manufacturing. The choice is therefore not between good and bad: it is between better or worse.

Figure 1. Global Primary Energy Consumption by Source

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Our World In Data; as of 31 December 2021.

Moving the Needle

What then, will make the most difference?

We should focus our efforts where they will make the most impactful difference.

In our view, a great deal of supposed ESG activity is misplaced on those stocks which score highly on more superficial ESG data monitoring tools. These are typically capital-light, knowledge intensive businesses which have little-to-no carbon footprint. However, these stocks are not isolated: while their Scope 1 and 2 emissions may be low, they are still enmeshed in the global economy. Nevertheless, by offering more capital to companies whose environmental improvement will only be incremental, we are wasting the leverage that comes from being a shareholder. With finite resources to deploy, we should focus our efforts where they will make the most impactful difference.

For investors to be effective, they need to improve the environmental position of those industries with the worst emissions. This overwhelmingly means power generation, transport and industrials, a grouping which also includes miners (Figure 2). Collectively, these areas account for around 85% of global emissions. Meaningful reductions in the emissions of these sectors will do far more to meet Paris Agreement goals than amassing a portfolio of stocks which already have high ESG ratings.

Figure 2. Share of World CO2 Emissions by Sector

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Climate Watch, the World Resources Institute (2020).

Engaging with the energy sector is fraught with risk.

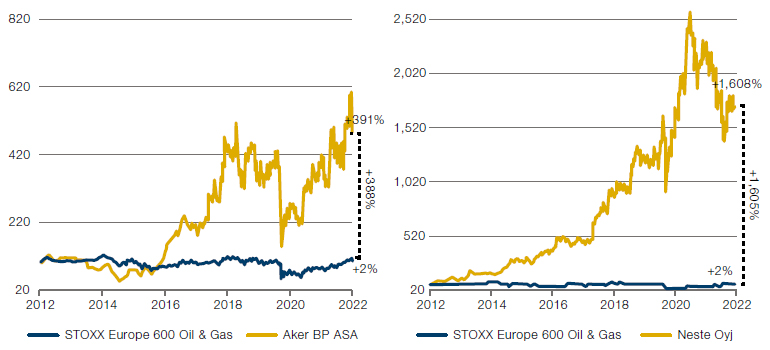

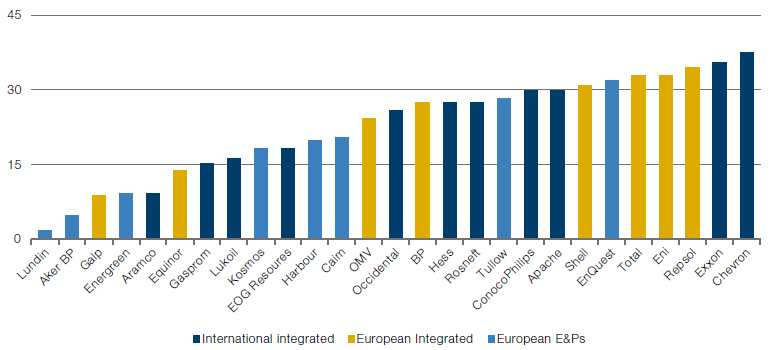

However, engaging with the energy sector is fraught with risk, both financial and reputational. Burning fossil fuels pollutes – there is no escaping this fact. The picture is complicated because some of the biggest renewable energy producers are also the biggest producers of fossil fuels. As such, reputational risk abounds. Prior to 2022, the implementation of ESG exclusion lists has caused both a lack of capital to the sector and a degree of price stagnation amongst oil majors (Figure 3). However, energy companies are not all alike, with great variation in the carbon intensity of production for different firms (Figure 4).

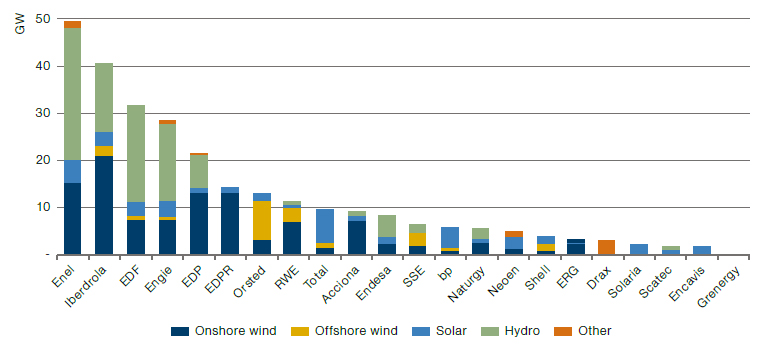

To mitigate the risk, as well drive the energy transition, investors must be selective. While in the short term, the ongoing supply squeeze will likely benefit most energy companies, over the long term the need for a transition makes it important to avoid those firms who are not changing their business models to adapt. Managers should avoid those firms with high emissions per barrel of oil equivalent and a high risk of stranded assets. Likewise those firms with a consistent track record of investing in lower carbon opportunities and renewables should be encouraged with further capital allocations: after all, these are the firms that are helping the world achieve its Paris targets (Figure 5). This means a degree of compromise, replacing coal and oil with a mix of natural gas and nuclear alongside renewables.

Firms pursuing a price over volume strategy, and those with non-diversified business models tied to commodity prices should be avoided.

Consider, for example, energy firms with high levels of buybacks. While we do not object to buybacks in principle, their primary purpose is to return excess cash to shareholders. Firms have excess cash if they have no good opportunities to invest it. As such, energy firms with significant buybacks are effectively signalling they do not wish to invest further. We would look askance at such an attitude, given the magnitude of the climate problem. Given that capex spend in the sector has been declining, quite clearly there is scope for energy firms to invest in increasing the size of their renewables operations (Figure 6). Likewise, those firms pursuing a price over volume strategy, and those with non-diversified business models tied to commodity prices should be avoided.

Figure 3. Price Return – Selected Energy Companies Versus the Index

Source: Bloomberg as of 3 October 2022.

Figure 4. Carbon Intensity of Operational Emissions per Barrel Produced (kg/barrel of oil equivalent)

Source: BofA Global Research as of 2021.

Figure 5. The largest renewables companies are within vertically integrated names. The pure players and oil majors are significantly smaller

Source: Barclays; as of 3 October 2022.

Figure 6. Capex Spending Decline in the Oil & Gas Sector

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Morgan Stanley as of 2021.

Firms which are committed to implementing principles of circularity in their business models will reduce their effect on the environment and should be supported.

Another major source of emissions is industry. Again, an ESG strategy which avoids owning industrial stocks is one without the purchase to encourage meaningful change. While industrial processes will remain resource intensive – in particular with regards to the demand for metals – there are a number of steps that can be taken by firms to ensure that emissions decline. Electrification and general shift away from conventional energy sources has the potential to create significant gains. Likewise, improvements in machine monitoring and maintenance and scenario simulation allow for a more sophisticated use of resources. Manufacturing techniques can be pioneered and refined without a trial-and error approach, with more timely maintenance extending machine lifespans, both of which lead to lower energy and resource consumption. Likewise, firms which are committed to implementing principles of circularity in their business models will reduce their effect on the environment and should be supported.

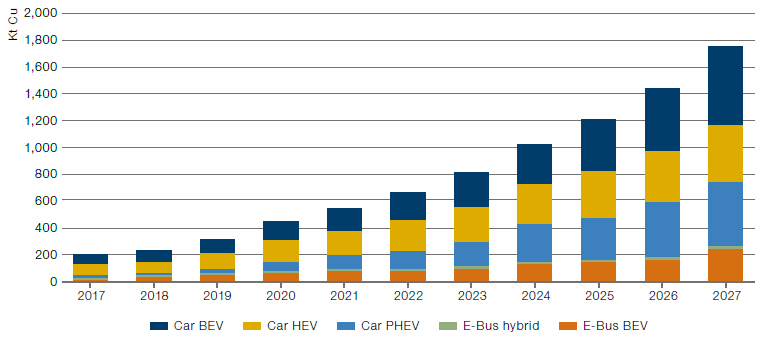

The point of electrification brings us neatly to the vexed question of mining. Any transition towards renewable energy brings a coincident requirement for ever greater supplies of battery metals, given the intermittent nature of most renewable methods of energy production. Likewise, there is an increasing demand for circuits. If projected targets for solar power in the US are met, the 262 gigawatts of new installation will require some 1.9 billion pounds of copper by 20272, which is around half of annual global production levels. This excludes projections for products like electric vehicles, which would place further burdens on supply chains (Figure 7). If we are to see an energy transition, there is a clear need for increased capacity in the mining sector.

Miners should be held to high standards of accountability, with dry separation techniques preferred to reduce water waste.

Again, trade-offs have to be made. Miners should be held to high standards of accountability, with dry separation techniques preferred to reduce water waste, and the implementation of rigorous safety standards when construction tailings dams. Those miners who can demonstrate that they take steps to mitigate their environmental impact should be supported; with demand for metals so high, the alternative is that it will be satisfied by those in the industry with no regard for the environment or dangerous artisanal mining, both of which are detrimental from the perspective of ESG.

Figure 7. Electric vehicle Cu demand

Source: International Copper Association; as of 2017.

Conclusion

Unhappily for us, we live in an imperfect world. To arrest climate change, we need a rapid energy transition. In the short term however, this involves unpleasant trade-offs if popular support for pro-environmental policies is to be maintained. As such, we need to take a pragmatic rather than utopian approach in putting our capital to work where it can make the most impact: in energy firms, in industry and in mining. Instead of being caught up in utopianism, we need to make hard choices to ensure that we see a smooth energy transition, where emissions come down – and the lights stay on long enough to enable it.

1. https://unfccc.int/news/climate-commitments-not-on-track-to-meet-paris-agreement-goals-as-ndc-synthesis-report-is-published

2. Visualizing Copper’s Role in the Transition to Clean Energy (visualcapitalist.com)

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.