Introduction

Bull markets run from recession to recession, as we have previously discussed, and we are clearly emerging with some vigour from the recession of the first half of the year: fiscal support for Covid-afflicted economies is strong and central banks are all in.

So why are we not more bullish on equities and credit?

The first thing to say is that the equity and credit markets have already exhibited a V-shaped recovery. The equity market and economic growth recovery has taken the shine off what our quant process identified as a very attractive market outlook over the last few quarters, without now giving any big sell signal. On its own, this would not be enough to reduce equity risk nor to raise bond risk.

It actually comes down to a combination of three or four other risks which, for now, we think will take the shine off equity market performance, and which restrain an extravagant equity risk weight but which are not enough to make us really bearish. These risks are, in order of perceived importance: the US election; the slowing second derivative of growth; some tightening in financial conditions; and the blasted virus.

The Fed’s Framework Review

We will briefly outline our thinking on these issues in a moment, but first we must take note of the most important development of the quarter just past, which, in our opinion, was the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy framework review. At a virtual Jackson Hole Fed Chair Jerome Powell announced the new policy of “flexible inflation targeting”, where this, in our view, was the key phrase:

“In order to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at this level, the Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2% over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2%, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2% for some time.”

This prompted much debate among the Kremlinologists as to what “moderately” and “for some time” mean, and one day that debate will matter. However, for now we can simply take the Fed at its (new) word and know that interest rates and other policy won’t be tightened until and unless inflation is above 2%. When might that be? Well, the clue to how the Fed itself is thinking is contained in the newly released Statement of Economic Projections, where Fed board members’ own expectations are summarised.1 Inflation is forecast to hit 1.9-2.0% only in 2023! Fed funds is still expected to be zero then. Assuming inflation did accelerate in 2024, the earliest we should then expect Fed tightening is some time late in 2024 or even 2025.

Figure 1. Federal Reserve Median Economic Projections

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Longer run | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in real GDP | -3.7 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.9 |

| Unemployment rate | 7.6 | 5.5 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| PCE inflation | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Core PCE inflation | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.0 | |

| Federal funds rate | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.5 |

Source: FOMC; as of 16 September 2020.

In short, this is an exceptionally dovish Fed, even in the context of the last two decades (and more) of very dovish Feds. It speaks of an organisation that is determined to change the deflation-prone narrative that has dominated and threatened the system over the last two decades. And we are very clear that determined policymakers willing to deploy both monetary and fiscal tools simultaneously can and will change inflation expectations, as we set out in great detail in our Inflation Regime Roadmap report earlier this year.

But before we can get to the bigger, longer-term picture of a determined and reflationary Fed, which would be exceptionally supportive of equity risk in the first instance, we need to get through the nearer-term risks listed above.

Risk One: The US Election

Certain sell-side analysts divide past US Presidential elections into tight and non-tight. In tight elections such as this one, where betting markets have it 52-48 to Biden but within the margin of error, the typical profile for the S&P 500 Index is for a sideways market between July and November as investors struggle with the uncertainty of the outcome, then a relief rally in the three months following the election. This time around, things might be different after Election Day (3 November) because if it’s as close as betting markets predict, the result could be contested. The last time this happened was in the 2000 election, when Al Gore conceded on 13 December, more than a month after the 7 November election. In the interim, the market fell 6% having been down 8% – although one should not draw too many conclusions given it’s a single instance and the market was in the middle of the epic TMT bubble bursting at the time. But if there were no immediate result, we believe the market would fall.

Thinking about market impacts after a result, our hunch is that a clear win for either candidate would be market friendly – the uncertainty would be cleared up. In a clear Biden win, the market may worry about tax hikes for the corporate sector, but would highly appreciate a large fiscal response from a new Democrat administration. In a clear Trump victory, the relief of no tax hikes would be appreciated and there may still be CARES2 or similar. The risk of a renewed trade war with China, which we think is real, might not be the market’s first concern although it would certainly be a risk in the phase that followed a relief rally.

Risk Two: The Slowing Second Derivative

To be clear, if growth holds up reasonably well, then a moderation in the growth rate will not be a market problem, in our view. But it is easily imaginable that the market could start to worry that a deceleration presages something worse. For one thing, fiscal thrust is almost certain to fade, possibly quite significantly. On current forecasts, economists estimate the cyclically-adjusted fiscal deficit will contract from 13% of GDP this year to 9% next, so a net tightening of 4% of GDP next year after a net loosening of 9% of GDP this year in response to the virus2. As we write, UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak has announced that the job support furlough programme will be scaled back by over 90%, from costing the government GBP4 billion per month to just GBP300 million per month (per million people supported). It feels inevitable that there will be a hit to consumption when very large numbers of people move from furlough to unemployed.

This must impact leading indicators and in turn market earnings estimates. On this front, estimates have been rising with the full year 2020 EPS consensus for the S&P 500 having risen from its USD125 trough to now USD131. This has undoubtedly been supportive of the market. But with next year’s consensus at USD166 (up 27% on this year), a lot of recovery is already baked in given an ‘as good as it gets’ multiple of 21x.

Risk Three: Tightening Financial Conditions

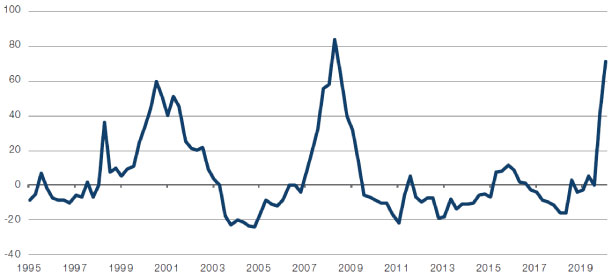

If the policy challenge now is to wean economies off emergency support programmes without crashing them, the job is being made harder by an undeniable tightening in monetary conditions. The Fed’s Senior Loan Officers Surveys are key to watch here. Lending standards are being tightened at a very rapid pace: a net 70% of banks have tightened conditions for commercial and industrial loans, and a similar 71% have tightened credit card lending standards. As large numbers move into ranks of the permanently unemployed, one should expect that personal bankruptcies and mortgage defaults will accelerate. This bears watching because creditors might be less willing to exercise the forbearance in a recovery that they exercised in the eye of the storm, partly for political reasons.

Figure 2. Fed’s Senior Loan Officers Survey, Net % Respondents Tightening Credit Standards

Source: Bloomberg; as of 30 September 2020.

Risk Four: The Blasted Virus

This leaves us with the virus. We are less concerned about the risk of another six months to a year of rolling lockdowns than one might assume – after all, so far USD10 trillion of lost global GDP has been met with USD21 trillion of fiscal support3, which assuming a fiscal multiplier of 0.5 or better will fill the hole over time. It’s more that the market is now expecting a vaccine to be available in fairly short order – and that has to be a risk factor in our view. President Donald Trump expects a vaccine by November. Bill Gates said in May between nine months to two years – so really, from towards the end of the first quarter of 2021 at the earliest. Take your pick, but the risk is that it’s not as effective as the market may now expect or that it’s simply not available for longer. It’s a risk but not the end of the world as far as markets are concerned.

Conclusion

It’s worth remembering that: (1) we have just had the recession, and although bankruptcies and defaults show up with a lag, equity bull markets run from recession to recession, which should incline us to an optimistic view; (2) monetary policy is set to remain exceptionally benign for years not months; and (3) while we have to get through the second derivative of fiscal policy turning down in coming quarters, starting now, ultimately we think we are in a new era of more supportive and extensive use of fiscal tools to support the economic recovery and to share the fruits of that recovery more widely than prior expansions have allowed. These are three very market friendly developments. It’s just getting there that restrains our optimism for now.

1. Source: FOMC; as of 16 September 2020.

2. Source: Morgan Stanley.

3. Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.