Introduction

How does a lightbulb illuminate the environmental challenges faced by consumer companies?

On the surface, it seems a silly comparison. ‘Consumer staples’ is a catch-all term, covering firms with products ranging from toothpaste to laundry detergent to Marmite. ‘Consumer discretionary’ encompasses everything from t-shirts to cars to dishwashers. How can one extrapolate an idea from a single product and then apply it to a diversity of business models?

Electricity was a necessity and demand for it was not going to go away any time soon. So, product innovation and supply-chain efficiency were also necessary to reduce its direct impact on the environment. The same goes for consumer companies.

The answer: resource efficiency, and innovation. First detailed by William D. Nordhaus in 19981, the cost of lighting using modern LEDs has fallen by a factor of 500,000 since Thomas Edison’s carbon filament bulbs of 1900. The labour that could once purchase 54 minutes of light can now purchase 52 years’ worth. It’s a staggering revolution, driven through the falling price of energy and the stunning increase in the efficiency of lighting technology. As technology shifted, so did the environmental impact of lighting. The discovery of petroleum “gave life to the remaining whales” as consumption shifted from whale oil to the new, cheaper alternative. While burning oil creates its own environmental problems, Moby Dick’s descendants can breathe a sigh of relief that they were not hunted to extinction to light our homes. As innovation progressed, LED lighting reduced the need to mine tungsten for filaments.

The lighting revolution illuminates a wider truth: electricity was a necessity and demand for it was not going to go away any time soon. So, product innovation and supply-chain efficiency were also necessary to reduce its direct impact on the environment.

The same goes for consumer companies. Consumers are not going to stop buying ‘staples’ upon which they rely on, or clothing or household appliances. Meanwhile, the global population is rising inexorably, compounding pressures on natural resources and supply chains, with clear environmental consequences.

If we wish to minimise these impacts, responsible investors (and consumers) need to have their own ‘lightbulb moment’. Product sourcing and production processes need to adapt (and fast), if we are to protect the finite global ecosystem on which we all rely.

Consumer Companies in Context

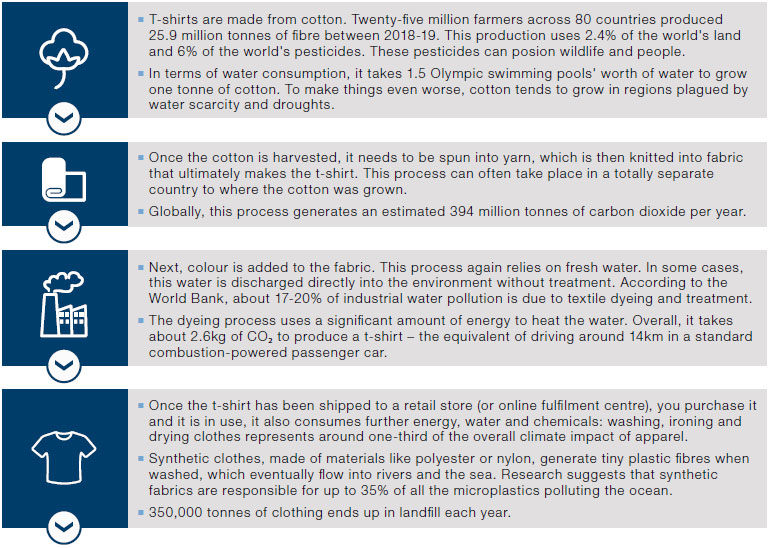

To really understand the impact of consumer companies on the environment, let’s track the lifecycle of a t-shirt from a cotton field to a landfill.

Overall, it can take up to 2,700 litres of water to produce the cotton needed for a single t-shirt. To put that in context – that’s enough water for one person drinking three litres a day for 2.5 years!

Overall, it can take up to 2,700 litres of water to produce the cotton needed for a single t-shirt. To put that in context – that’s enough water for one person drinking three litres a day for 2.5 years!2

Cotton production has already had a tangible environmental impact: once the world’s fourth-largest lake, the Aral Sea has now almost completely dried up. The reason? In 1918, the Soviet Union decided to divert water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers that fed the Aral Sea for agricultural irrigation, specifically cotton production. By the 1980s, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya dried up before reaching the lake, causing it to shrink rapidly (Figure 1).

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: NASA Earth Observatory.

Left image shows the lake as of 25 August 2000. At the start of the series in 2000, the lake was already a fraction of its 1960 extent (yellow line). Right image shows the lake as of 21 August 2018.

Cotton is just one example. Palm oil – used in lipstick, soaps, detergents and even ice cream – has had a devastating impact on the environment. Today, 3 billion people in 150 countries use products containing palm oil. Globally, we each consume an average of 8kg of palm oil per annum.3 However, palm oil production has been, and continues to be a major driver of deforestation of some of the world’s most biodiverse forests, destroying the habitat of already endangered species like the orangutan, pygmy elephant and Sumatran rhino – driving them towards extinction. Eighty-five percent of palm oil production comes from Malaysia and Indonesia. Fires deliberately set to clear forests for palm plantations are the top single source of greenhouse gas emissions in Indonesia.

The Lightbulb Moment

So, what’s the lightbulb moment for consumer firms?

As we said above, consumers are not going to stop buying items upon which they depend.

The onus is therefore on firms that manufacture these goods to use responsible judgement in their supply chain, as well as innovating in their production methodologies.

Fortunately, firms are not having to innovate from scratch. Progress has already been made in a variety of production methods which create core products for consumer firms. For instance, studies of cotton production methods have shown that there are significant environment benefits if companies adjust their processes.4 Firms using organic cotton cultivation and renewable energy sources manage to deliver a 70% decrease in the global warming potential of production when compared with traditional methods. Likewise, acidification potential and eutrophication potential (excessive plant and algae growth in water sources) can be reduced by half. If recovered5cotton fibres (instead of new cotton) were used as the raw material, these figures fall by 47%, 90% and 96%, respectively. As an additional benefit, because these fibres have already been through the dyeing process, the need for colour treatment is also greatly reduced.

Beyond the product itself, these companies also face a challenge in addressing packaging. Through the Covid-19 pandemic, global retail eCommerce sales grew by more than 25%6, driving demand for boxes and plastic packaging up dramatically. Superfluous packaging represents a major environmental burden. A number of consumer companies are already taking steps to address this issue. Action can take one of two forms – the elimination of unnecessary packaging wherever possible or replacement of existing packaging with a recyclable, bio-based or biodegradable version. Procter & Gamble, for instance, have launched a reusable aluminium bottle for haircare products. When used in combination with recyclable refill pouches (which use 60% less plastic), this has the potential to significantly reduce bathroom waste (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Packaging Substitution Case, Sweden

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: McKinsey & Co; as of January 2020.

In addition to the obvious environmental benefits, transforming production processes can also offer a way for firms to become more competitive.

As commodity prices rise, if businesses want to defend margins, they must be more efficient in their use of resources. They need to use less, even as they strive to sell more.

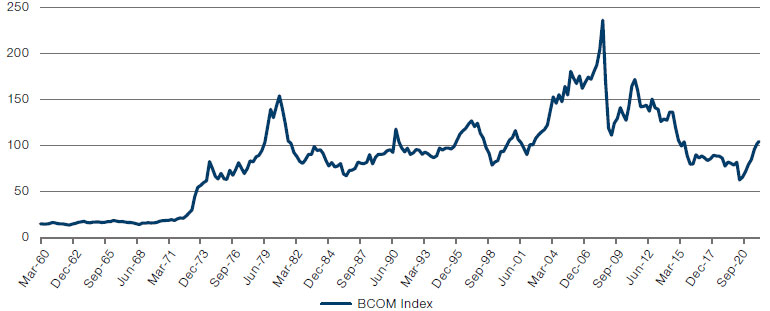

The steep decline in commodity prices in real terms was a major engine of corporate earnings in the 20th century. This state of increasing abundance fashioned relatively wasteful business models, even as general prosperity increased. If commodities are cheap, there is no need to be concerned about the resource intensity of a manufacturing process, nor to consider new techniques or recycling. After all, businesses usually do not pay an upfront cost when the environment is damaged. It is only the absence of commodity abundance which tends to drive innovation. Commodity abundance therefore contributes to business models which are hard on the environment.

However, commodity prices fluctuate wildly (Figure 3). This has profound implications for consumer staples businesses, which are often the biggest listed purchasers of commodities. Put simply, they have to change too: as commodity prices rise, if businesses want to defend margins, they must be more efficient in their use of resources. They need to use less, even as they strive to sell more.

Figure 3. Commodity Prices Tend to Fluctuate

Source: Bloomberg; as of 17 November 2011.

Is it enough for 10% of the content of a product to be ‘sustainable’? Should everything from manufacturing process to ingredients to packaging to logistics be ‘sustainable’ for a product to qualify?

As technology innovation continues apace, companies have a wide range of options available to reduce their environmental footprints, and increasingly limited excuses not to act. We welcome mid-term targets and net zero goals by 2040 or 2050, but what really is required is immediate, decisive and definitive action. We would like to see companies committing to sustainable and responsible sourcing across as much of their supply chain as possible and therefore sustainable products and services representing the majority of company offerings, rather than a minute fraction of the total. Key to this is how we define a ‘sustainable product’. Is it enough for 10% of the content of a product to be ‘sustainable’? Should everything from manufacturing process to ingredients to packaging to logistics be ‘sustainable’ for a product to qualify? Here, we would argue for pragmatism and realism over idealism. In a perfect world, fossil fuels would be immediately and entirely disintermediated from supply chains, companies would use 100% renewable energy in their production processes, all ingredients would be natural and organic and packaging would be 100% recycled. Unfortunately, we recognise that as with the energy transition, this must be a process, not a light switch on or off.

That isn’t a reason not to make any effort, though. We would like to see progress in sustainable content of supply chains and products delineated in the same way that emissions reductions targets are, with milestones (e.g., 50% of supply chain sustainable by 2030; 20% of products classified sustainable by industry standards by 2025) both in the near and long term. To achieve this, we would like to see formal commitments to auditing and switching out of suppliers not meeting sustainability standards as rapidly as feasible. We need more collaboration across industries to establish relevant sustainability standards in suppliers and products, pledges to reduce packaging use and/or switch to recyclable or bio-based alternatives, investment earmarked to deliver sustainable innovations, and undertakings to offer consumers as many sustainable products as possible. Significant and sweeping change must happen now, but to deliver on 100% sustainable or responsible products may take some time. To accelerate this shift, it is likely policymakers will have to intervene, given one of the most effective drivers of corporate transformation is regulation or legislation (as seen with micro-plastics or plastic straws, for instance). True change in the corporate world ultimately depends on buy-in and pressure from everyone from end consumers to regulators.

Changing Consumer Tastes

Those companies who embrace a more sustainable approach will find themselves tapping into a growing consumer trend. According to IBM, by 2020, some 57% of consumers were willing to change their purchasing habits to reduce negative impacts on the environment, and 71% were prepared to pay a premium for products which could provide this security.7

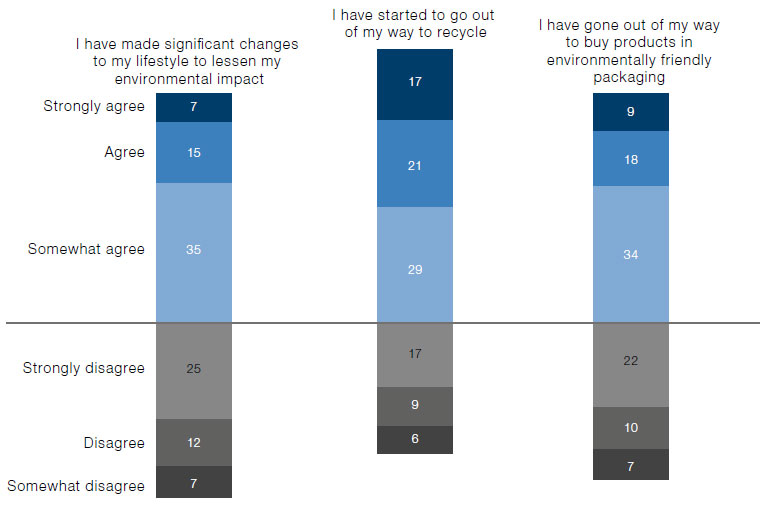

This trend has only been reinforced by the coronavirus pandemic. About 60% of respondents to a McKinsey survey said that the pandemic prompted them to change their lifestyle to reduce environmental impacts, recycle more and buy environmentally friendly packaging (Figure 4). As such, there seems to be a growing addressable market for those firms who are able to pivot and provide consumers with what they want: products with a smaller environmental impact.

Figure 4. Change in Consumer Behaviour During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Source: McKinsey & Co; as of July 2020.

Note: Numbers shown are % of respondents; n = 2,004.

It is certainly easier to consider the environment when the choice between good and bad behaviour is clear and environmentally friendly choices are enabled. We can all remember a time when we failed to recycle simply because there was no obvious bin.

However, we would go further than simply identifying a trend for the sector to take advantage of. Firms must also take the opportunity to shape consumer views through education. They need to be proactive in explaining exactly how their products have changed for the better, and offer consumers a wide range of environmentally friendly choices at a reasonable price point. Consumers may not always behave virtuously, but it is certainly easier to consider the environment when the choice between good and bad behaviour is clear and environmentally friendly choices are enabled. We can all remember a time when we failed to recycle simply because there was no obvious bin. If firms can signpost the environmental benefits of their new products, consumers will find it much easier to behave well, creating a virtuous cycle where responsible production becomes the norm and is then rewarded by increased sales.

Conclusion

We need a lightbulb moment for consumer companies. On the precipice of a global climate crisis, it’s very clear things cannot go on as before.

We need to remember that innovation is not only possible, but essential, to improving the quality of products, at the same time as reducing resource consumption. In our view, those firms who can transform their production processes, becoming less resource intensive and more environmentally friendly, are best placed to thrive in the consumer sector. If they do so, they will be well placed to take advantage of a growing desire on behalf on consumers to shop in a more responsible fashion.

1. William D. Nordhaus, ‘Do Real-Output and Real-Wage Measures Capture Reality? The History of Lighting Suggests Not’.

2. https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/the-impact-of-a-cotton-t-shirt.

3. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/feb/19/palm-oil-ingredient-biscuits-shampoo-environmental.

4. Source: Clean Technologies & Environmental Policy, “Life cycle assessment of cotton woven shirts and alternative manufacturing techniques”; Kazan, Akgul, Kerc; May 2020.

5. Recycled materials require reprocessing into a new form before being reused. By contrast, recovered materials are ready to be used in their current form, and can immediately replace new material without further reprocessing.

6. Source: Statista.

7. IBM, Haller, Lee & Cheung “Meet the 2020 consumers driving change: Why brands must deliver on omnipresence, agility, and sustainability”.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.