How Much Can the US Government Borrow?

Like a lot of governments during the coronavirus pandemic, the size of the US government debt has increased, and rapidly. Indeed, the US has almost USD8 trillion of debt to refinance in 2021 (Figure 1).

In a world of rock-bottom interest rates, this isn’t necessarily a problem, as the US is able to refinance its debt relatively cheaply. Indeed, at her confirmation hearing for the office of Secretary of State for the Treasury, Janet Yellen made a clear case for using the environment of low rates to spend more. However, at some point, continued expansion of debt will test the limits of public sector borrowing, limits that we will not be able to identify until we hit them.

There are two main buyers for US Treasuries – overseas creditors and the Federal Reserve. In theory, at some point foreign official creditors will demand a higher interest rate to absorb expanding bond issuance. Left unchecked, higher rates would be uncomfortable for economic expansion. Another option is for the Fed to continue to buy the debt, expanding its balance sheet, and raising the threat, for some, of a rise in inflation. How big this risk is the great unknown – we have had more than a decade where stubborn inflation refused to budge at all.

As Figure 2 shows, there has been an identifiable uptick in the amount of US debt owned by the Fed, whereas foreign ownership has stayed relatively flat. So far, this suggests that the inflationists have more to worry about than those who worry that a rising stock of debt will push interest rates higher. Ultimately, the constraints on public sector borrowing will be a lively debate we expect to hear much more of over coming years, particularly if the Biden administration shifts towards more sustained fiscal spending.

The best thing we have read on it to date comes from a St Louis Fed blog earlier this month: “There is presumably a limit….[but] we can only know once we get there.”

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 27 January 2021.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 1 February 2021.

They’re Trolling Us

We’ve previously written of how prospects for stocks valued at EV/sales >20x don’t look good: using the Russell 1000 and MSCI World, stocks above 20x EV/sales average a cumulative relative underperformance of 42% and 22%, respectively, with a median cumulative underperformance of 73% and 50% (Figure 3).

In what feels like a direct rebuke to our considered analysis in the fourth quarter of 2020, data from the middle of January show that these stocks now account for around a quarter of trading volumes in the US (Figure 4), a figure which is in the 96th percentile since 1985. This surge has come alongside other concentrations of unusual factor attributes in the share of trading volume: the volume participation of stocks with share prices below USD1 is in its 99th percentile, and those with negative trailing EBITDA are in the 100th percentile.

Strange times indeed.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Man Numeric; as of 31 August 2020.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Compustat, Goldman Sachs; as of 21 January 2021.

The Roaring Twenties? UK Savings and the Wealth Effect

We have some sympathy for those who think that we will emerge from the coronavirus pandemic into the ‘Roaring Twenties’, a decade characterised by high demand as consumers spent their savings. After all, the savings rate in the UK has steepled in the wake of the pandemic (Figure 5).

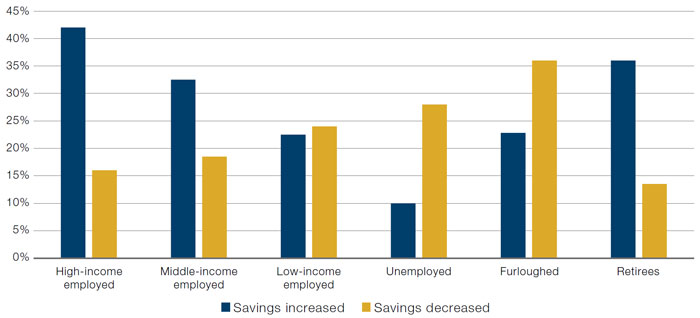

However, we would urge a note of caution to this idea. The majority of excess savings in 2020 was distributed to higher income households and retirees, which have a lower marginal propensity to consume than those on lower incomes (Figure 6). This challenges the notion that there is a tidal wave of pent-up savings ready to hit the economy: 2021 may see a meow instead of a roar.

Nevertheless, there are reasons for optimism. In contrast to the Great Financial Crisis, the wealth effect observed in 2020 was positive, with a rise in asset prices such as equities and housing (Figure 7). In addition, consumer credit balances have been significantly paid down during 2020. If these are rebuilt as lockdowns are lifted, and the excess savings are actually deployed, then we could see buoyant consumer spending to boost the UK recovery.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 25 January 2020.

Figure 6. Higher Income Households and Retirees More Likely to Have Increased Savings During Covid-19

Source: Bank Of England; as of 25 November 2020.

Note: High-income employed households are households where the main earner is either employed or self-employed and the household income is in the top quintile; middle-income employed households are households where the main earner is either employed or self-employed and the household income is in the third or fourth quintile, and low-income employed households are households where the main earner is either employed or self-employed and the household income is in one of the bottom two quintiles. Retirees are households where the main earner is retired.

Figure 7. UK Wealth Effect 2020 Versus 2008

| Index | December 2008 | December 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| UK Nationwide House Price YoY | -15.9% | 7.3% |

| FHFA US House Price Index YoY | -10.1% | 7.8% |

| MSCI World Local YoY | -40.1% | 11.7% |

Source: Bloomberg; as of 31 December 2020.

With contribution from: Ed Cole (Man GLG, Managing Director – Equities) and Dan Taylor (Man Numeric, CIO).

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.