Background

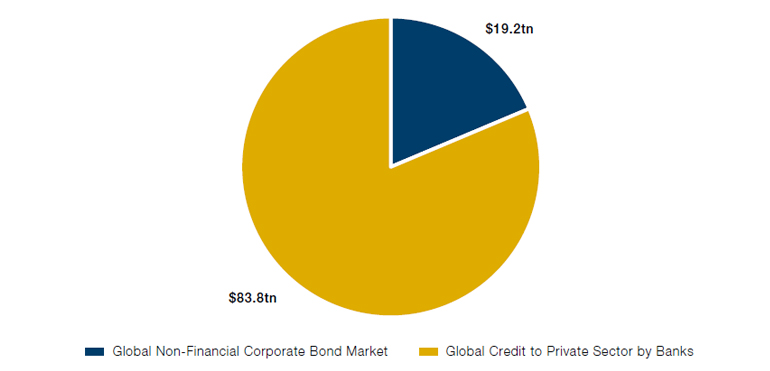

The allocation and provision of credit to the private sector is in fact dominated by the global banking system – not corporate bonds.

When describing credit markets, investors and investment managers often define the available universe as synonymous with the public bond markets (and, perhaps, middle market and other leveraged loans).

Seemingly unnoticed by investors, however, is that the allocation and provision of credit to the private sector is in fact dominated by the global banking system – not corporate bonds. The approximately $20 trillion1 in the corporate bond market is lilliputian compared with the roughly $84 trillion2 of loans (and yet more in undrawn credit facilities) to the private sector sitting on the balance sheets of banks around the world.

Figure 1. Outstanding Corporate Credit

Source: ICMA and World Bank; data as of August 2020 (ICMA) and December 2020 (World Bank).

Of course, banks have been under increasing pressure to optimise their balance sheets in the years since the Global Financial Crisis. Techniques such as securitisation (the process of converting portfolios of loans into tradable securities) have helped in this regard: in the US, for instance, mortgage loans now account for only 10% ($2 trillion) of bank assets3, while six times as much ($12 trillion) is outstanding in mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

Securitisations, however, are traditionally applied to large pools of relatively homogeneous and highly transactional loans such as mortgages, or relatively high-yield corporate loans, where the spread is sufficient to generate returns to investors at a given rating (such as in collateralised loan obligations, or CLOs). These markets are able to absorb trillions of dollars of banks’ exposure each year, but even that still leaves large amounts of capital-intensive yet high-quality credit exposure on the balance sheet of the global banking system.

CRS Unlocks a Market

Banks and investment managers alighted on a simple yet robust structure to transfer the economics of core “on balance sheet” exposures to the capital markets, known as Credit Risk Sharing (‘CRS’). This approach has appealing characteristics for both banks – who can use CRS for capital optimisation – and investors, who can gain access to portfolios of high-quality credit instruments.

Unlike traditional securitisations that seek to minimise the cost of funding assets, CRS securitisations are explicitly structured to capitalise exposures. Some investors were therefore quick to realise, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, that CRS could be leveraged to improve bank capital ratios. Later, as regulatory capital ratios began to normalise at much higher levels, bank managers used CRS to optimise the amount of internal capital they held against various exposures.

Throughout this period, CRS transactions performed well above most investors’ expectations, leading to a greater appreciation of the attributes inherent in bank exposure and the CRS security structure. These include:

- Core Relationships: While true-sale securitisations transfer title and therefore lender-of-record status, CRS transactions leave title with the lender, making them ideal for distributing core relationship lending exposure.

- Structure: Since senior tranches are retained by the sponsoring bank, cash flows need not be structured to entice AAA investors. Instead, cash-flow protection rests in the distributed junior tranche, improving the performance characteristics of the security.

- Obligors: Various reference obligor (debtor) exposures are not otherwise available in the capital markets.

- Credit Quality: Banks are heavily exposed to commercial obligors with implied or actual ratings of Single-A to Double-B, making bank portfolios substantially lower risk than weighted average credit risk in the tradable bond and loan markets.

- Seniority: Reference obligations are typically senior (i.e. with higher priority of recovery in bankruptcy) to bonds and loans available in the capital markets.

- Workouts: Banks are able to work with troubled obligors to prevent poor credit event outcomes.

Why CRS Exists

In theory, banks can sell or distribute any loans or securities on their balance sheets. And in practice, they do this many thousands of times each day as they trade bonds, syndicate loans, or – following a process of building sufficient diversification – issue mortgage- or asset-backed securities.

This business of banks acting as agents to intermediate flows from buyers of credit to sellers of credit has been going on nearly as long as banking itself. In the last two decades of the 20th century, however, banking began to transition as regulation increased the importance of asset liquidity and credit risk assessment and pricing.

Suddenly, “distribution” was no longer a valve that banks could use to reduce leverage or manage loan exposure; it became the primary mechanism by which banks built borrower and institutional asset-manager relationships, gained market share and ultimately increased service fee income. The ability to lend, unconstrained by deposits or capital, catalysed the growth of banking, private-sector credit and the capital markets. By the turn of the millennium, leading banks saw themselves not as in the “warehouse” business but in the “transportation” business.

Even with the explosion of asset distribution, however, plenty of credit exposures didn’t fit well on the balance sheets of other entities and so remained dominated by bank lending channels. Each of these loan categories has features that inhibit or prevent distribution. CRS synthetic securitisations offer the easiest and most robust solution for banks to reduce the amount of capital they hold against these exposures. Several examples help to illuminate this:

- Unfunded revolving credit facilities: Unfunded facilities obviously fit poorly into the structurally “funded” capital markets. CRS, however, allows banks to retain the funding component to which they are uniquely well suited, while investors gain access to fully collateralised corporate credit-risk mitigation – essentially a highly capital-efficient bond portfolio with enhanced protection in bankruptcy.

- Funded term loans to small- and medium-sized companies: Small and Medium Enterprise (‘SME’) loans are often priced to very tight spreads given the low leverage and substantial security associated with these loans. Since CRS securitisations, unlike traditional cash securitisations, are not built around funding, banks can continue to implicitly fund these loans at very tight spreads while investors gain access to extremely granular commercial loan portfolios with relatively high yields.

- Loans with substantial data sensitivity: Finally, many loan agreements either contain language a) preventing their distribution or b) providing competitive insights into a bank’s lending programmes. In both instances, banks are essentially unable or unwilling to provide flow markets with the information they need to efficiently securitise and distribute these loans.

Benefits of CRS

In our view, the unique characteristics of CRS securitisations create a mutually beneficial market for both investors and banks.

Figure 2. Potential Benefits of CRS for Investors

For illustrative purposes only.

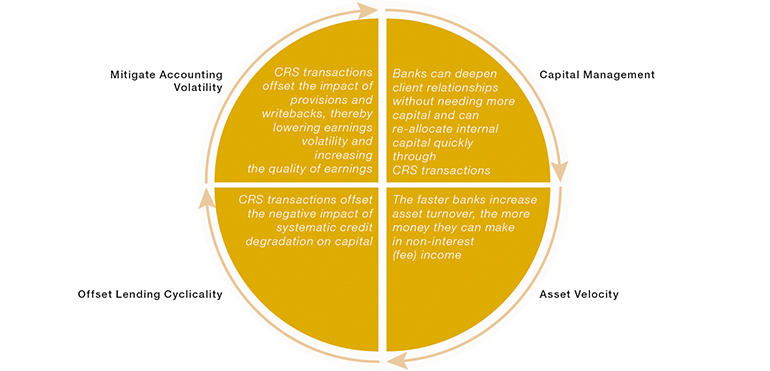

Figure 3. Potential Benefits of CRS for Banks

For illustrative purposes only.

CRS as an Asset Class

A universe of high quality and heterogeneous credit exists just beyond the reach of traditional credit markets.

In short, a universe of high quality and heterogeneous credit exists just beyond the reach of traditional credit markets. Specialised investment managers, with skills in corporate credit, structured credit and bank analysis, are able to access these markets to seek to generate high risk-adjusted returns.

We believe the resulting securities are a compelling proposition in the capital markets. Sellers (banks) can substantially improve allocated capital efficiency and increase asset velocity while retaining important client relationships and their attendant fee income streams. Buyers (investors), meanwhile, can receive low-beta, high-quality, and predictable cash flows tied to contractual obligations not otherwise available or replicable in the capital markets.

There was €126 billion of outstanding synthetic securitisations as of Q1 2019.4 According to the European Banking Authority, “The predominant asset classes continue to be large corporates and SMEs followed by trade finance…There has been a trend in the diversification of the asset classes, which now also include specialised lending (including infrastructure loans), commercial real estate, residential real estate, trade receivables, auto loans, micro loans and farming loans.”

Given the defensive attributes of the asset class and the efficient allocation of capital against exposures, we expect the market growth experienced over the past decade to continue. With new assets and new issuers coming to market, however, we believe experienced managers will become ever more key to navigating the market’s risks and rewards.

In subsequent articles, we will explore the characteristics of the CRS market in greater detail.

1. www.icmagroup.org/market-practice-and-regulatory-policy/secondary-markets/bond-market-size/

2. data.worldbank.org/indicator/FD.AST.PRVT.GD.ZS

3. www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/

4. Source: European Banking Authority, Report on STS Framework for Synthetic Securitisation under Article 45 of Regulation (EU) 2017/2402, 6 May 2020.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.