Key takeaways:

- The last five years have been tough for emerging market (EM) companies. With the Federal Reserve having just cut interest rates for the first time since 2020 – a significant tailwind for EM – now is an opportune time to revisit the asset class

- In the EM corporate bond space, misconceptions about risk, liquidity and the relationship between sovereign and corporate bonds persist. While this has led some to overlook the asset class, it has also created idiosyncratic opportunities

- In EM equities, getting top-down country calls correct is no longer enough. The surge in the availability of locally-sourced alternative data has enhanced quants’ ability to identify attractive companies from the bottom up

Introduction

The last five years have been challenging, to say the least, for emerging markets. An unstable geopolitical landscape, Chinese economic weakness, a global rate-hiking cycle and a strong US dollar, among other factors, have meant many investors have given both EM equities and bonds the cold shoulder.

However, with the Federal Reserve (Fed) having begun to cut rates and further cuts anticipated before the end of the year, it is an opportune time to revisit this asset class and to ask whether now is the time to reconsider allocating to these areas.

Focusing specifically on EM hard currency corporate bonds and EM equities, we will take each market in turn, consider how they have evolved and outline why we believe both markets lend themselves to a bottom-up approach. In the case of EM corporate bonds, misconceptions abound, leading many investors to erroneously tar all bonds with the same, particularly by aligning sovereign and issuer-specific credit risk. In EM equities, a data revolution has created fertile ground for quants to leverage local insights to uncover leading companies.

Part I: EM corporate bonds: overlooked and misunderstood

EM hard currency corporate bonds have come a long way in a relatively short space of time. Prior to the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), they were predominantly traded by macro hedge funds in the form of single-name credit default swaps (CDS). After the GFC, disintermediation and EM’s increased market share from a GDP perspective allowed the asset class to grow rapidly – expanding at approximately 10% year-on-year between 2008-2019.

More recently, the path has not been quite so smooth. Defaults in the Chinese property sector, a very large component of the index, dominated news headlines, compounded by some of the challenges we identified in the introduction, caused growth to stumble. More recently, many EM companies have opted to borrow locally given cheapness relative to hard currency markets. For reference, the EM corporate bond hard currency universe is now estimated at US$2.5 trillion versus US$0.6 trillion in 2008. Simultaneously, the EM corporate bond local currency universe has grown from US$1.6 trillion in 2008 to around US$11 trillion currently.1

The hard currency corporate bond market includes quasi-sovereigns (bonds issued by non-government entities but which are usually backed by the government) and while it has significantly lagged local currency growth post Covid, we believe it has strong potential to return to its former trajectory, as obstacles faced in recent years begin to diminish.

Rate cuts may provide a tailwind

The first of these obstacles is higher interest rates. We have just seen the Fed cut rates by 50 bps – the first cut since 2020 – and further cuts are expected by the end of the year.

Why is this so significant for EM corporate bonds? Firstly, interest rates in most EM countries are currently above where they should be (based on traditional metrics such as employment statistics and inflation). Yet they could not risk devaluing domestic currencies versus the US dollar by cutting rates before the Fed. Now that the Fed has started to cut rates, those countries will likely follow suit, which will be supportive for fixed income, with hard currency issuance becoming far more attractive. As always with EM, there are a few outliers, such as Brazil, which is once again raising interest rates, but on the whole, we can expect the sector to follow in the Fed’s footsteps.

Too risky: perception, or reality?

It is no secret that the geopolitical landscape in EM has been turbulent in recent years. This, alongside some high-profile defaults, has led some investors to label it too risky. But is this just perception, or reality?

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Contrary to popular belief, the EM corporate bond universe is predominantly investment grade (IG) with an average rating of BBB. This is largely owing to the number of quasi-sovereign issuers, as well as issuance from several big banks. Further, EM companies are traditionally less levered than their developed market (DM) counterparts, with a higher portion of secured liabilities, as the average rating would suggest. On top of this, investors are currently being compensated for investing in EM bonds with higher credit spreads.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

On the fundamental side, default rates over the last 10 years are relatively low, aside from the Chinese property sector which heavily skewed the index after 2022. In Figure 3 below, we compare default rates in the US high yield market with those in the EM high yield market since 2014.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Sovereign bonds ≠ corporate bonds

A further point to note, which is not always widely appreciated, is that defaulting or coming close to defaulting on sovereign bonds will not always result in corporate defaults in the same country. We saw examples of this in 2023 when Argentinian sovereign debt narrowly avoided another default, yet many Argentinian companies, predominantly in the energy sector, demonstrated solid fundamentals and competent risk management, as well as a willingness and an ability to pay their debtors. This has led to a stark difference in the performance of corporates versus the sovereign, as well as significantly negative correlation.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

A further example of this is Turkey which, at a macro level, was in serious trouble at the beginning of this year due to persistent hyperinflation. However, several companies remained solid in fundamental terms, proving their creditworthiness was not linked to that of the country, despite what prices may have suggested.

We have seen the same occur in parts of Africa. Typically, corporates which issue hard currency debt in Africa are few, and concentrated in the energy, metals and mining sectors. Here, sovereign debt default can even be a tailwind for the company if the product they are selling is priced in dollars. In this sense, hard currency issuance can act as a hedge for domestic volatility.

The Argentinian, Turkish and African case studies above are examples of how negative sentiment about a country, which frequently manifests as market volatility and/or selloffs, can create opportunities for active managers willing and able to dig below the surface to uncover idiosyncratic value. In general, EM corporate bonds are priced in line with sovereign debt plus some pick-up (and in fact some EM corporates have credit ratings effectively capped by their corresponding sovereign), but fundamentally-oriented investors have the flexibility to discern between companies which are genuinely impacted and those which are being unjustifiably affected by negative sentiment.

Assessing the risks

As referenced earlier, the geopolitical landscape has been tumultuous in recent years and continues to be the biggest risk EM faces today. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was an important lesson for EM bond and equity investors alike and showed how quickly and dramatically the market can change, with Russia removed from the index and many Ukrainian companies classified as special situations.

Crucially, in geopolitical crises less extreme than that of Russia/Ukraine in 2022 which saw bonds lose almost all of their value, bottom-up, active managers can not only react faster but also discern the level of risk and adjust a portfolio accordingly. In such cases, an active approach allows managers to identify fundamentally solid companies unfairly caught up in the noise, which present potential relative value opportunities.

While geopolitical risk persists, election risk has diminished. In 2024, dubbed the year of the election globally, we have seen some unexpected results in EM, including in South Africa where votes for the African National Congress fell considerably; India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party fell short of a majority in the lower house of Parliament; and Mexico where a wider-than-expected victory for the ruling party served to heighten local political risk. While we will continue to closely monitor local political risk, the crucial point is that most elections in EM are now out of the way, offering some additional stability to the asset class and reducing election risk for the coming years.

Rising local demand boosts liquidity

We have now addressed misconceptions about EM corporate bonds in relation to quality and default risk, both of which can open up idiosyncratic, bottom-up opportunities. Another common myth is that liquidity in EM markets is predominantly provided by developed markets. The reality is that local demand has become increasingly meaningful.

The infeasibility of raising debt capital through hard currency bonds due to higher interest rates in DM countries in recent years meant issuers relied on local lenders, who replied in earnest. By way of example, following the Turkish sell-off in the first quarter of 2024 referenced above, local investors bought the dollar-denominated bonds of many Turkish companies as a means of protecting not only their capital but buoying the domestic market.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

In short, several misconceptions about risk, liquidity and the relationship between sovereign and corporate bonds persist. While this has led some to overlook EM corporate bonds, particularly over the last five years, it has also created idiosyncratic opportunities for savvy, selective investors able to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Part II: EM equities: harnessing data to unearth opportunities

The EM equity market has also undergone significant changes in recent decades. Before 2000, investors could generally outperform by getting a handful of top-down country calls correct but this has since shifted. This is, in part, due to secular trends such as globalisation, market integration, as well as the convergence of economies across EM as many governments and central banks have adopted similar economic policies.

As a consequence, today’s EM equity investors cannot rely on the traditional model of investing in a subset of countries. Instead, the focus has shifted to the idiosyncratic component given factors such as how each company is run and managed, its profitability and its earnings outlook are having a greater impact on its stock performance. This has long been the case in DM but not EM historically.

Figure 6 clearly illustrates that aside from a brief period dominated by the collapse of the Russian equity market, country dispersion in EM has markedly narrowed while idiosyncratic dispersion has increased.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

A data revolution in EM

Against this backdrop, it has become vital to have an informed view of each of the approximately 5,000 stocks which comprise the EM universe. Historically EM was opaque and thus having fundamental managers on the ground locally was necessary to gain insight into companies. However, the data revolution we have witnessed in EM in recent years has shifted this dynamic, putting quantitative investors who can leverage alternative data sources effectively while maintaining robust risk management on a strong footing.

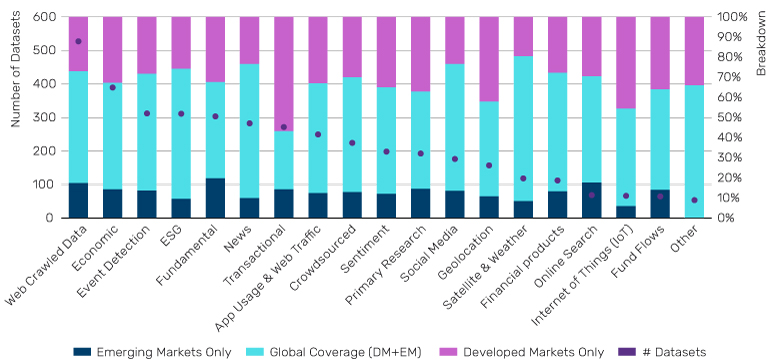

Figure 7 compares alternative data sets by category and shows that most categories now have EM coverage. Moreover, in select areas, such as consumer-related data, some Asian markets are now ahead of many developed markets. Take China, for example, which has in recent years emerged as the second largest market after the US for alternative data.

Figure 7. Abundant data sources in EM

Source: Neudata, Man Numeric, as of December 2022.

The widespread deployment of technology has been the primary driver of this data explosion, reflecting the acceleration of internet-based activities, including social media, digitisation of local news, financial services and ecommerce in general, all of which generate data. Regulatory requirements in EM differ from those in DM. In the case of geolocation and consumer activity tracking, they are not always as stringent as those in DM. In other areas, regulation compels EM companies to disclose more information than in DM. In both cases, this leads to a greater number of information sources. Finally, EM economies tend to be more heterogeneous than DM in terms of the economic structure, creating greater opportunities for the development of new data sets.

Making the most of it

Yet it’s not enough simply to acquire the data. It requires modelling expertise and market knowledge to overcome holes and gaps, to clean and restructure, to adjust methodologies as needed, and to conduct robust backtests that take into account any integrity issues. Historically, translation and nuances of local culture have made textual data more difficult to process but advancements in AI, such as improved natural language processing (NLP) and greater experience in handling non-English data is yielding better results. This can require significant resources, but the corollary is the potential advantage that comes with being one of the first to commoditise the data.

Applying machine learning to decode EM market dynamics

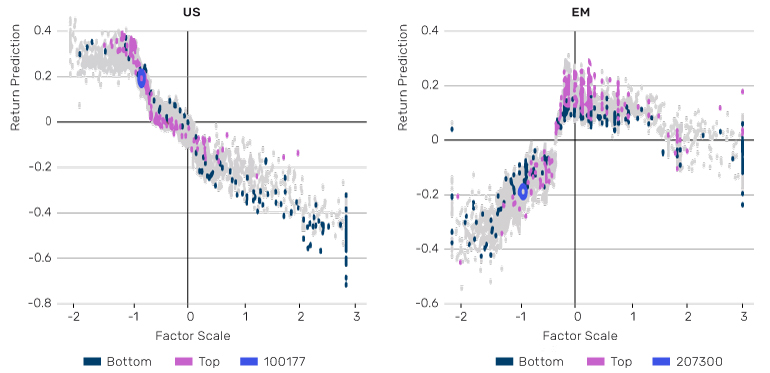

Machine learning is also becoming increasingly useful in capturing EM specific phenomena. To take one example, short interest (the number of shares that have been sold short relative to total amount of shares available for short sale) is a well-known factor in most markets. As a rule, if a company in DM has a very high short interest, it tends to have lower future performance, as illustrated in the left-hand chart in Figure 8. This is unsurprising and has been traded in the US for decades.

Figure 8. Applying machine learning to capture EM-specific phenomena

Source: Man Numeric, as of Q1 2024.

This cannot simply be ported into EM, which has a very different payoff pattern. If a company has very high short interest, it tends to underperform, as in DM. However, where there is very little short interest, it also underperforms, which is very different to DM. This is broadly owing to the restrictions on shorting in some parts of EM. For example, in the China A-share market, there is very limited shorting activity while India does not allow it at all and South Korea recently banned it. Clearly, the market structure is very different in EM, driving a very specific payoff pattern. Machine learning can serve as a valuable tool for understanding phenomena like this, at scale (for hundreds of factors and in over two dozen markets), complementing company-specific information gleaned from alternative data sources and ultimately assisting quantitative managers in uncovering opportunities.

Conclusion: tailwinds from rate cuts and enhanced data sets

We have highlighted how both the EM corporate bond and EM equity markets have evolved and the opportunities they present to investors today. In the high yield corporate bond universe, defaults on China property have played out and, as we have shown, default rates are otherwise relatively low. Company fundamentals look solid, supported by consistent and diversified liquidity, while the Fed has started to cut interest rates, offering tailwinds aplenty for EM companies.

In equities, we believe the days of it being enough to get a few country calls correct are decidedly over as EM company performance is increasingly being driven by idiosyncratic factors. In this context, it has never been more important to have an informed view of each stock in the EM universe. As the breadth – and depth – of available data in the region continues to increase, quantitative investors are well-positioned to assess the whole universe, as well as to apply machine learning techniques to identify EM specific market dynamics and to uncover the most attractive opportunities from the bottom up.

1. Source: JP Morgan

Important Information

ICE BofA Emerging Markets Corporate Plus Index, ICE BofA US Corporate Index, ICE Argentina Government Index and ICE BofA High Yield Emerging Markets Corporate Plus Argentina Issuers Index, ICE BofA Global High Yield Index and ICE BofA High Yield Emerging Markets Corporate Plus Index are products of ICE Data Indices, LLC and is used with permission. ICE® is a registered trademark of ICE Data Indices, LLC or its affiliates and BofA® is a registered trademark of Bank of America Corporation licensed by Bank of America Corporation and its affiliates (“BofA”), and may not be used without BofA’s prior written approval. The index data referenced herein is the property of ICE Data Indices, LLC, its affiliates (“ICE Data”) and/or its third party suppliers and, along with the ICE BofA trademarks, has been licensed for use by Man Group. ICE Data and its Third Party Suppliers accept no liability in connection with the use of such index data or marks.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.