Key takeaways:

- AI is among the most important technologies of the last century. But the AI industry has been built for a demand curve that may not arrive and whose economics may deteriorate if it does

- AI-related exposure is increasingly metastasising through the economy. This quiet migration of risk is the bubble’s distinctive feature

- We believe the winners will be those who solve the fundamental economic problems AI faces. The losers will be those who monetised the temporary imbalances of the buildout phase

Introduction: a boom built on leverage, not adoption

The AI boom is real, but the financial structure built around it appears to be expanding more quickly than we believe any credible adoption curve can justify. This is not a new phenomenon. Across every major technological revolution – railroads, electrification, radio, fibre optics, and the dot‑com era – the technology itself has endured, but the financing cycle has broken, with expectations outpacing the industry’s ability to meet them. It increasingly appears to us a question of when, not if, the AI bubble bursts.

This paper seeks to clarify the mechanics of the AI cycle at year-end 2025: the recursive demand loops, off‑balance‑sheet leverage, distorted demand signals, and the most likely paths of unwinding. While we believe wholeheartedly in the transformative power of this technology, we also know markets and their propensity for overreach.

The historical pattern: technology manias always lead with capital

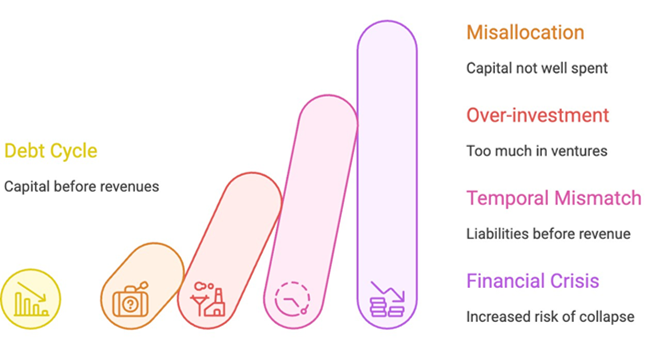

Figure 1. Debt-fuelled capex cycle impacts

Source: Paul Kedrosky. Schematic Illustration.

Every general‑purpose technology arrives wrapped in financial excess. Markets price the world that might exist – not the one that does – pulling forward decades of investment ahead of real usage. High capital expenditure (capex) waves require significant debt and thus higher amounts of leverage. We believe the current debt-fuelled AI capex cycle, powered by data centre spending, is among the most intensive in modern business history.

Rising valuations justify heavier capex; rising capex signals explosive future demand; the signal itself reinforces valuations. When the revenue curve fails to steepen in time, the loop breaks.

This cycle’s distinguishing feature is its financing structure accompanied by naïve extrapolation of the current surge in demand into the future.

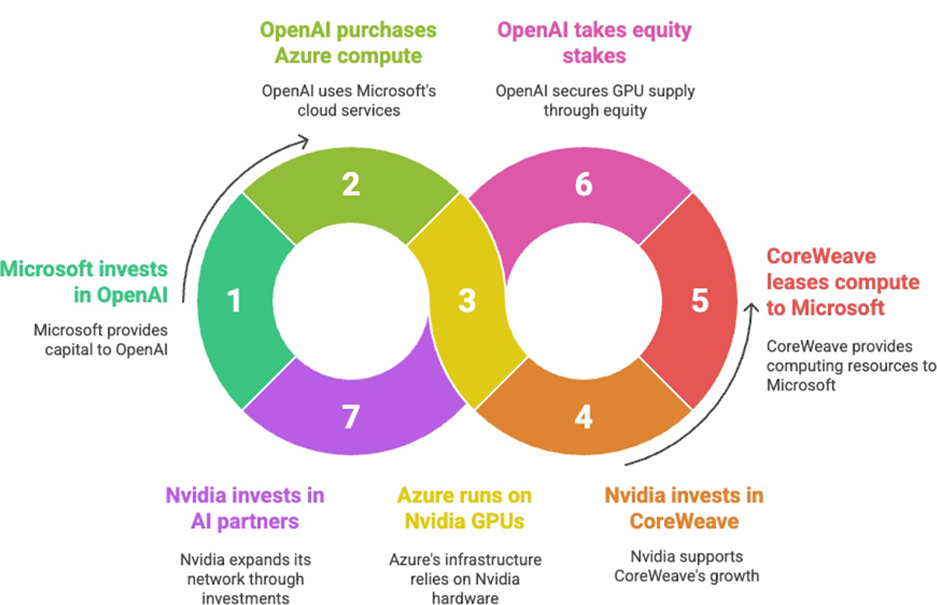

Closed-loop financing: the hyperscaler recursion problem

The modern AI cycle is a closed, recursive financing loop across hyperscalers and their strategic partners. A handful of mega‑caps – Microsoft, NVIDIA, Amazon, Meta, Google, OpenAI, and Anthropic – act simultaneously as suppliers, customers, investors, and validators. (Figure 2)

Non-financial forms of investment add further complexity. For example, a cloud compute provider, like Microsoft, might “invest” in OpenAI through cloud compute credits, a currency that can be used nowhere else. Similarly with Amazon and Anthropic.

Figure 2. Modern AI financing cycle

Source: Paul Kedrosky. Schematic Illustration.

What are the real costs? Who are the real buyers? Revenue growth can appear spectacular because each node in the loop pays another. Capex looks justified because demand from inside the loop appears endless. But the demand signal becomes circular and divorced from the market.

Circular relationships also increase the overall risk in the market as these recursive loops generate two systemic risks:

- Reflexive demand - one firm slowing investment causes revenues to fall across the entire cluster

- Mispriced capacity - capex decisions rely on internal signals rather than independent market validation

What makes this cycle particularly dangerous is that industry participants are behaving somewhat rationally when viewed individually. Given the existential nature of this technology, hyperscalers face genuine competitive threats if they fall behind in AI. Each firm's decision to invest heavily thus appears defensible in isolation.

Yet collectively, the behaviour is deeply irrational. The major models are converging to remarkably similar solutions and capabilities. There’s massive duplication: multiple companies training similar models, building overlapping infrastructure and bidding up the same constrained resources – high-bandwidth memory (HBM), power capacity, and data centre space.1

Furthermore, unlike past technology bubbles, where public market discipline could eventually reassert itself, the AI megacaps are largely insulated from such pressures given their unusual governance structure.2 There is no effective check on capex acceleration.

Off-balance-sheet infrastructure: where the real leverage lives

During the early part of the current cycle, hyperscalers funded most of the capex from their own cash flow. This created a natural rate limit on growth and on the resulting system risk. That changed in 2025, as data centre spending soared, absorbing an ever-larger share of earnings (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The quarterly capex spending of AI giants

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Respective company financials, as of 31 October 2025. Shows calendar year quarters. Microsoft’s full year ends in June and that of Amazon, Google and Meta ends in December.

This increased spending had two effects. First, technology companies began looking for new sources of non-dilutive capital. This coincided with the rise of private credit, a trillion-dollar asset class eager to lend to good credits (major tech firms) on long-term ventures with high yields.

Secondly, a financing template was found. Bespoke debt financings are difficult to do at scale. Instead, capital providers want a model that they can take to would-be borrowers so they can quickly pull together financing – again and again. Given the supposed US$2+ trillion gap3 between current funding sources and data centre buildout plans over the next few years, this is all that was needed to light a financing fire.

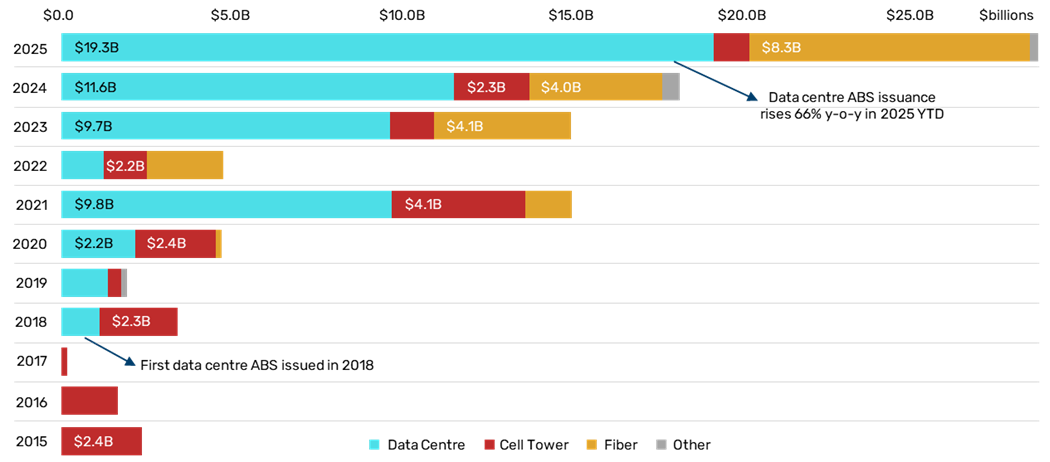

One financing template is to use the project assets as collateral in a legal structure where the income generated pays for the financing. Called ‘asset-based financing’, this is common in commercial real estate and increasingly being applied to data centres4 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Data centre asset-backed securities (ABS) growth reflects AI buildout’s shift to debt – issuance of ABS tied to data centres has surged since 2018 and is expected to grow

Source: BofA Global Research. Data for 2025, as of 15 October 2025. Chart created by Lucy Raitano on 3 November 2025.

A recent example of the ABS template is Meta’s US$30 billion Hyperion project. In that case, only 20% of the cost sits on Meta’s balance sheet while the rest is in a separate vehicle.

Hyperscalers can now push liabilities outward onto special purpose vehicles, infrastructure funds, private credit, insurance company balance sheets and even, indirectly, into data centre real estate income trust ETFs.

The off-balance-sheet financing structures being deployed contain a fundamental and dangerous expectation mismatch. Private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) investors are placing their bets with a familiar model: hoping for one in 10 investments to deliver 100x returns. This power-law approach has served them well in software and internet investing, where marginal costs are near-zero and winner-take-all dynamics prevail.

Meanwhile, creditors funding these projects – banks, insurers, pension funds, private credit vehicles – believe they are financing long-lived infrastructure assets comparable to commercial real estate or utility-grade equipment. Their underwriting models assume seven-to-15-year useful lives, with stable cash flows and recoverable collateral values.

However, the effective economic life of GPU and ASIC chips is approximately one year. A data centre filled with NVIDIA H100s in 2024 faces severe competitive disadvantages against one with Blackwell chips in 2025 and potential obsolescence with the next architecture.

This means that depreciation schedules are too long, collateral values in default are illusory, and cash flow assumptions are fragile. The VC and PE investors understand this: their short time horizons and equity-like returns compensate for high risk. But lenders do not appreciate the precipitous drop in asset values and token pricing they are exposed to. This duration and usage-risk mismatch is being masked by the financing templates and the apparent credit quality of the hyperscaler tenants. We believe it represents a ticking time bomb in credit markets.

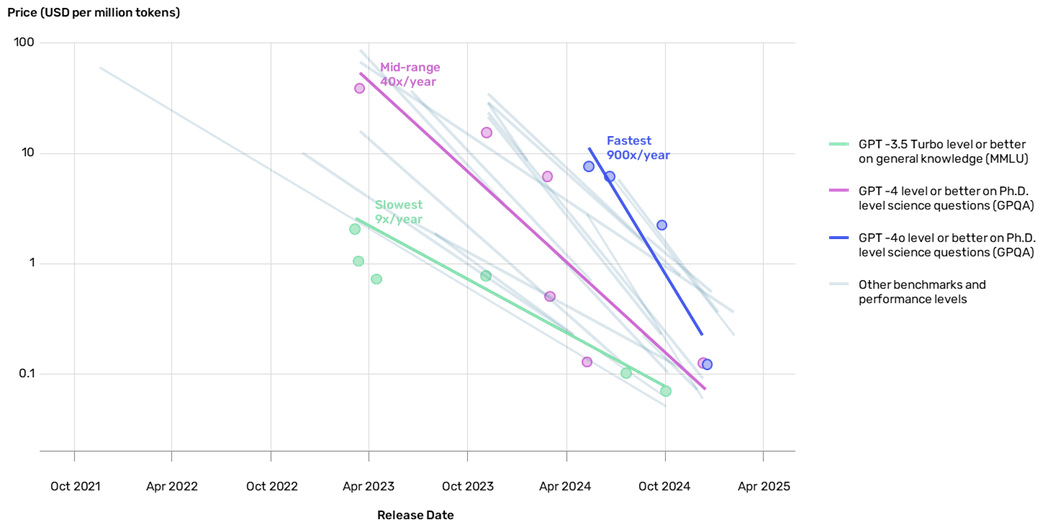

While demand for tokens is soaring, that demand isn’t rising nearly quickly enough to make up for collapsing unit economics, as efficiency gains drive down token costs more than 70% per year (Figure 5). Merely standing still would require an increase of more than 225% in tokens demanded per year.

Figure 5. Token cost falling exponentially

Source: Epoch AI, Artificial Analysis (logarithmic scale).

The demand gap: US$200 billion capex versus US$12 billion in revenue

AI infrastructure investment is expanding at a rate that bears little resemblance to actual economic uptake. Worse, AI’s unit economics don’t benefit from traditional software leverage: when usage scales, compute must scale (at least) linearly. Unlike search or office software - where incremental users have near-zero marginal cost - AI remains compute-intensive at every step.

Data-centre activity today is dominated by two categories: training – intensive, bursty, capital-heavy and model-centric; and inference – the recurring work needed to serve users.

Training dynamics are misunderstood…

The foundational leap in current large language models (LLMs) was the exploitation of the public internet. That, by definition, is not repeatable.

The effect is that current training cycles are fundamentally different – exponentially more expensive, with training times stretching into months and even years. Most capability improvement now comes from reinforcement learning, preference tuning and agentic looping (none of which compensate for pre-training inadequacies). Reinforcement learning generates more tokens, worsening unit economics, with more tokens per query and higher inference costs. Cycle times for new model versions increase with no evidence that new releases will unlock meaningful, economically justified new capability.

Training is no longer a growth driver. Rather, it is a cost centre with diminishing returns.

… as are inference dynamics

Inference is the other piece of data centre workloads and must be at the core of AI’s future economics.

Today’s inference workloads are dominated by two categories5: role-playing and conversational entertainment, which is very difficult to monetise; and coding assistance, which is highly price sensitive.

Inference loads through role-play sessions and extended coding feedback loops are high-token, low-monetisation tasks. As competition increases and efficiency improves, token prices are falling faster than inference demand can rise, placing the entire cost structure under pressure.

Historically, bubbles narrowed the capex–revenue gap as adoption caught up. In AI, the opposite is happening: hyperscalers are doubling GPU orders despite sluggish AI revenue growth, meaning that capex is accelerating while revenue growth is stalling, a divergence that compounds with each hardware cycle.

A common defence argues that the US$200 billion+ capex was necessary for pre-training and incremental inference revenue won't require proportional spending. While true, this misses critical points: first, falling token prices means inference revenue projections must account for volume growth not translating to revenue growth. Second, training-optimised infrastructure is poorly suited for inference economics – the US$200 billion created the models but also overcapacity and a cost structure incompatible with inference unit economics at scale.

Furthermore, enterprise AI adoption is narrow (concentrated mainly in software), and demand data shows hypersensitivity to price-per-token, with minimal stickiness. Chinese/open-weight models now approach 25% share,6 eroding moats and pressuring pricing and margins.

Second-order systemic effects

The ramifications will be felt far beyond the tech firms themselves as AI-related exposure metastasises through the economy:

- Utilities are expanding generation and transmission for hyperscale demand that may not last

- Data centre operators are increasingly dependent on single-tenant hyperscaler leases, creating renewal cliffs and concentration risk

- Insurers are taking duration risk by financing long-lived power and real-estate projects tied to a short, volatile tech cycle

- Retail investors, via interval funds, REITs,7 and yield products, are indirectly exposed to AI-leasing SPVs and infrastructure credit (compounded as “alternative” investments enter retirement funds)

Market signals from the supply side

Some of the most important signals about the sustainability of the AI capex boom come from its suppliers.

Memory and semiconductor manufacturers are limiting capacity expansion despite the apparent insatiable demand for their products. HBM prices have reached astronomical levels – in some cases representing half the bill-of-materials cost of an NVIDIA Blackwell chip – yet manufacturers like Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron are cautious about bringing new fab capacity online.

These companies have been through multiple semiconductor cycles and don't believe in the AI capex projections themselves, understanding that:

- Overcapacity in memory leads to catastrophic price collapses

- GPU architectural generations turn over rapidly, creating demand volatility

- Today's training-focused workload mix may not persist

- The gap between capex and revenue in AI cannot be sustained indefinitely

The unwinding: how the bubble bursts

A modern bubble only needs a break between expectations and leverage. The most probable unwind begins with a plateau – not a collapse – in hyperscaler capex. Next, we consider some hypothetical scenarios:

Scenario One: capex compression from a major hyperscaler

If even one hyperscaler cuts GPU orders by 20–30%, the effects cascade mechanically (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Hyperscaler GPU order cuts trigger widespread economic cascade

Source: Paul Kedrosky. Schematic Illustration.

Scenario Two: data-centre overbuild

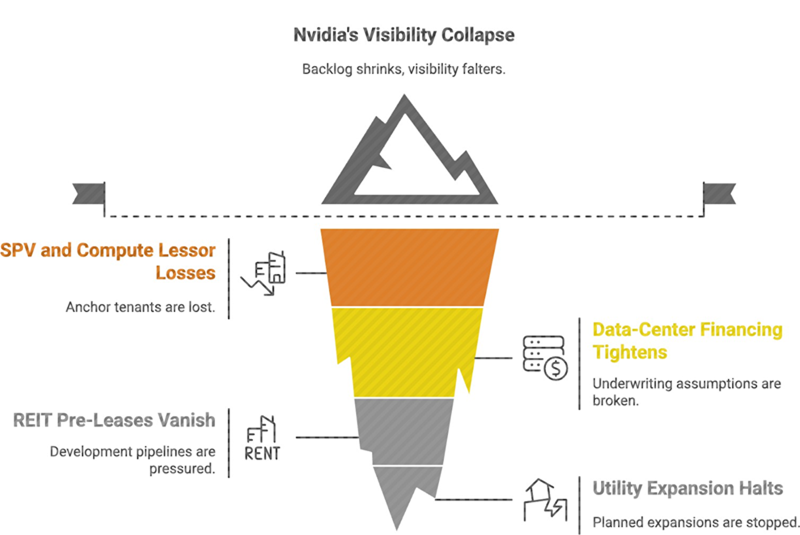

If utilisation remains low as new data centres come online, the overbuild becomes visible:

- Compute SPVs struggle to refinance at higher rates

- Data centre operators face rent compression and concessions

- Private-credit vehicles take persistent net asset value (NAV) write-downs, even if that is initially masked by make-whole clauses in lease contracts

This mirrors the telecom fibre bust, where physical capacity far outstripped monetisable demand.

Scenario Three: breakdown of the recursive loop

The sector is a synchronised machine: OpenAI drives Microsoft’s spend, Microsoft drives NVIDIA’s orders, NVIDIA drives SPV buildouts, SPVs drive utility expansions. If any node slows, all nodes slow.

We are already seeing an example of this dynamic beginning to fracture: Microsoft has pulled back from its right-of-first-refusal commitment to provide all OpenAI's compute needs. Instead, Microsoft is allowing Oracle and neo-cloud providers to fill the gap. As an original AI flag-bearer, Microsoft has become more methodical and discerning on its AI investments, even at the cost of opening up investment opportunities to its key competitors, a development which we regard as highly significant.

Paradoxically, the industry collectively continued to pursue massive infrastructure investments even as Microsoft was signalling caution. This is the recursive loop problem in action: no single actor can afford to be the first to slow down, even as rational analysis suggests collective restraint is optimal.

Scenario Four: private credit stress

Private credit lenders are modelling AI infrastructure investments as 10-to-20-year assets, comparable to commercial real estate or telecom towers. Their loan-to-value ratios, covenant structures and return expectations all assume stable, long-duration cash flows from assets that retain significant residual value throughout the loan term.

The reality is that every 12-18 months, GPU technology changes fundamentally – and each new generation requires an entirely different data centre architecture. This means the data centre lifetime assumption is deeply incorrect. Even if the building persists, the revenue-generating capacity of the infrastructure degrades precipitously as technology evolves.

Worse, these are predominantly single-tenant assets. Unlike multi-tenant commercial data centres, there is no deep secondary market of alternative tenants.

We believe the reckoning will come in year three. By then, the first generation of data centres will be two technology generations behind, hyperscaler tenants will be evaluating renewals versus newer facilities with better economics, token prices will have fallen 90%+ from initial underwriting assumptions and utilisation rates will be visible. What the collateral creditors believed was worth 70-80 cents on the dollar may be worth 20-30 cents – or less if there's no viable tenant for previous-generation infrastructure.

This scenario is not a liquidity crisis; it is a solvency crisis. The assets are impaired, not temporarily distressed. And because private credit operates outside the traditional banking system – with no access to central bank facilities, no deposit insurance, and limited regulatory oversight – the workout process will be opaque, protracted, and potentially disorderly.

The reality is that private credit lenders are holding subordinated exposure to technology-cycle risk, with collateral that depreciates like smartphones, not buildings. The first wave of defaults will likely emerge in 2027-2028, as initial lease terms come up for renewal and the gap between underwriting assumptions and reality becomes undeniable.

Indicators to watch

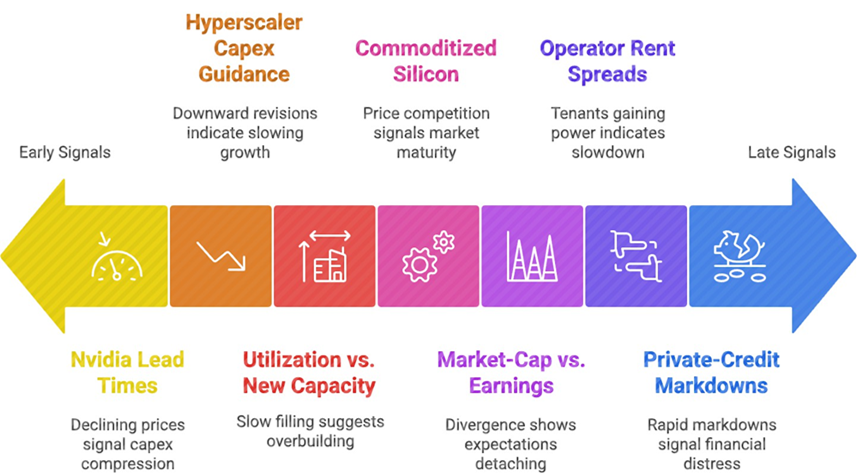

Figure 7 illustrates some of the most important indicators to watch:

Figure 7. Data centre capex risk indicators range from early to late signals

Source: Paul Kedrosky. Schematic illustration.

Investment implications – who survives and who doesn't?

Three categories of winners:

- Companies that reduce AI token costs – companies (such as chip designers, software optimisation firms) that can deliver inference and training at lower cost per operation

- Companies that distribute AI efficiently – deployment infrastructure and distribution networks will become valuable (enterprise software platforms, edge inference companies)

- Companies that keep training economical - those that can source or generate the next data frontiers

The losers: moment-in-time plays:

- Data centre operators and financiers – the tech industry is working aggressively to improve performance-per-watt. Assuming that current power and space demands will persist – or grow linearly – is a fallacy

- Power production supply chain – technological breakthroughs are likely to require much less power for each AI query going forward. Power infrastructure built for 2024-2025 demand levels risks becoming stranded assets by 2027-2028

Conclusion: the technology will survive, the financial footprint may not

We believe the financial architecture surrounding AI has become oversized, overleveraged, and too dependent on a small set of interconnected actors.

At the same time, risk is increasingly migrating away from tech company balance sheets and into institutions – utilities, insurers, data centre operators, private credit funds, pensions, and retail vehicles – that do not see themselves as betting on GPU cycles.

When the unwind arrives, however, many leading firms will survive and prosper. The technology is real. Applications will emerge. The companies solving fundamental cost and distribution problems will thrive. But we believe that the financial architecture built on overleveraged bets, short-duration assets financed with long-duration debt, and circular demand signals is unsustainable.

1. Chinese AI development has followed a different path: cheaper, more coordinated, and increasingly focused on efficient diffusion models rather than ever-larger monolithic large language models. Companies like DeepSeek, Zhipu AI, and Baidu have achieved capabilities with a fraction of the capital expenditure, partly due to export controls forcing innovation in efficiency, and partly due to greater coordination – sometimes voluntary, sometimes state-directed – that reduces duplicative spending. Open-weight models from Chinese labs now command roughly 25% market share in some segments, applying continued global price pressure.

2. Founder control with super-voting shares (e.g., Meta (Mark Zuckerberg)); or God-like leadership status (e.g., Microsoft (Satya Nadella), NVIDIA (Jensen Huang) and Tesla (Elon Musk)).

3. Swezey, V. (2025, November 10): AI’s $5 trillion data-center boom will dip into every debt market, JPMorgan says.

4. This template uses the asset projects as collateral in a legal structure where the income generated pays for the financing, This sort of project financing is common in commercial real estate and increasingly applied to data centres (CSC Global. (2025): Project Finance at an Inflection Point: Adapting to New Realities). It, in turn, permits the creation of asset-backed securities.

5. Aubakirova, M., Atallah, A., Clark, C., Summerville, J., & Midha, A. (2025, December). State of AI: An empirical 100 trillion token study with OpenRouter. Andreessen Horowitz; OpenRouter Inc.

6. ibid, OpenRouter.

7. Up to 25% of many popular REITs total assets are in data centres.

The organisations and/or financial instruments mentioned are for reference purposes only. The content of this material should not be construed as a recommendation for their purchase or sale.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.