Introduction

Recep Tayyip Erdogan may well be the most important leader Turkey has had since Kemal Ataturk; the man regarded as the father of modern Turkey. Indeed, superficially, there are many similarities between the two men, each seeking to re-make Turkey in their own image. But unlike Ataturk’s vision for a secular Turkey that survived the best part of a century, Erdogan’s Turkey faces serious challenges. Turkey is involved in multiple disputes with its neighbors, including a dispute with Greece over access to the Mediterranean and ongoing entanglement in the Syrian civil war.

However, President Erdogan’s biggest challenge remains at home. Turkey’s economy is quickly deteriorating, with very unorthodox economic and monetary policies pushing the country towards the point of no return.

Unless President Erdogan puts a brake on economic growth at home, we believe the country will face a balance of payment crisis in the near future. This will force the government to confiscate local dollar deposits and implement capital controls.

Recorded on 2 October 2020

How Did We Get Here?

After accepting an IMF programme in 2001 after a financial crisis, Turkey enjoyed rapid economic growth, with an average increase in GDP of 7.14% between 2002 and 2007. In addition to the post-bailout reforms, and similar to other emerging market (‘EM’) countries, Turkey was also a beneficiary of global growth, driven by Chinese economy. In fact, Turkey came out of the Global Financial Crisis (‘GFC’) much better than many of its peers, as its financial sector had relatively limited bad assets and cleaner balance sheets. As a country with a structural current account deficit requiring foreign investments, Turkey then was the beneficiary of low global interest rates and subsequently quantitative easing, which flooded EM countries with cheap money as investors were in chase of higher yielding investments.

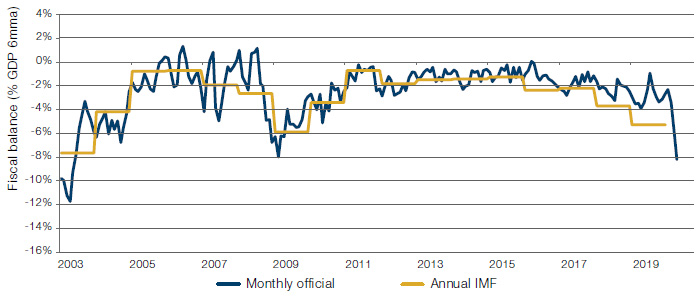

The selloff in oil prices in 2014 and 2015 was another bonus for the Turkish economy. As a large energy importer (with an average energy import deficit of 4.5% of GDP over the last decade), the oil price crash reduced the size of Turkey’s current account deficit. On the back of these economic developments, President Erdogan consolidated political power, removing opponents and reducing checks and balances on the executive power. Instead of applying economic reforms and addressing structural issues, the Turkish economy was allowed to run hot, fueled with cheap credit and an expansion of the construction and real estate sectors. And in order to maintain popular support for his administration, President Erdogan ran an expansionary fiscal policy, combining increased public wages and subsidies with tax cuts.

Figure 1. Six-Month Moving Average of Turkish Fiscal Balance

Source: Emerging Advisors Group; as of 19 August 2020.

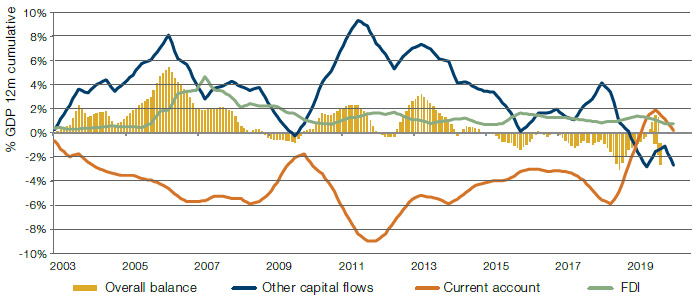

Turkey has been running a current account deficit of more than 4% of GDP per annum since 2009. Prior to that, foreign direct investments (‘FDI’) had provided much of the funding to maintain a positive balance of payments (illustrated by the green line in Figure 2). After 2009 however, the balance of payments deficit has been financed by foreign portfolio investments and Turkish companies borrowing abroad (as illustrated by the blue line in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Turkey’s Balance of Payments

Source: Emerging Advisors Group; as of 19 August 2020.

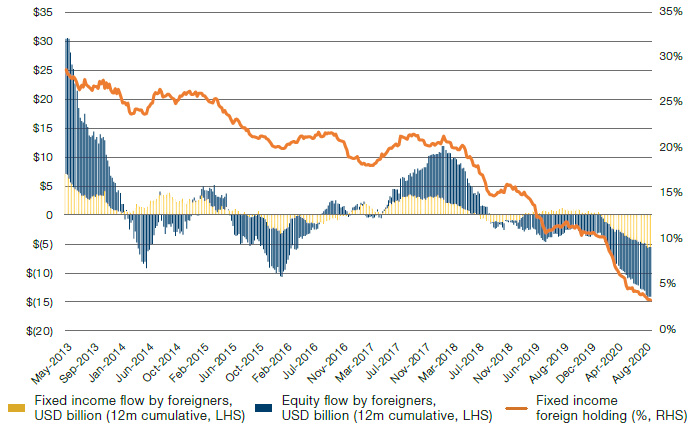

As Figure 2 illustrates, since 2015, the sum of capital flows and FDI on a 12-month cumulative basis has not been enough to finance Turkey’s current account deficit. This coincided with quantitative easing (‘QE’) tapering in the US and Turkey’s further involvement in Syrian civil war, which eroded investors’ confidence in the country. In addition, President Erdogan consolidated his grip on power by changing the constitution and moving to a presidential system in 2014, which was followed by an attempted coup in summer of 2016. All three factors combined to push foreign investors out of Turkish assets. As of 28 August, 2020, foreign holding of local bonds has dropped to less than 4% of total holdings, compared with the high of almost 30% back in 2013 (Figure 3). Indeed, just in the first eight months of 2020, foreign investors have taken out USD5.5 billion from the Turkish equity market and USD7.7 billion from local fixed income, according to the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (‘CBRT’).

Figure 3. Foreign Holdings of Turkish Assets and Capital Flows

Source: CBRT; as of 28 August 2020.

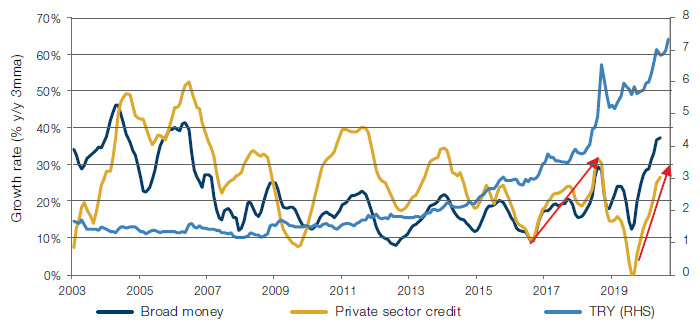

Between the coup in summer 2016 and the general elections in mid-2018, Turkey went on a credit-fueled economic expansion, which put pressure on both the current account as well as the Turkish lira. This eventually led to a sharp selloff in the summer of 2018 (Figure 4). Eventually, the CBRT had to tighten monetary policy by increasing the interest rate to 24%. Much to President Erdogan’s dissatisfaction, the tightening of the monetary policy slowed down the economic activity, but it was enough to turn around the current account deficit. However, this led to the replacement of central bank governor.

Entering 2020, Turkey had already started another credit expansion by lowering interest rates and putting pressure on local banks to extend loans to consumers, with some authorities going so far as to fine banks whose balance sheet did not carry enough consumer loans (illustrated by the yellow line in Figure 4).

Figure 4. Money and Credit

Source: Emerging Advisors Group, Bloomberg; as of 19 August 2020.

Central Bank Interference: The Mother and Father of All Evil?

President Erdogan is a fierce opponent of high interest rates, which he has often characterised as “the mother and father of all evil”. His views and actions have curbed CBRT independence and its ability to apply tight monetary policies to control high inflation and the weakening lira when needed. When Murat Cetinkaya, the previous governor of the CBRT, successfully tightened monetary policy to control high inflation, President Erdogan berated him for the economic slowdown, and ultimately replaced him. Since then, partially aided by the deflationary forces generated by former Governor Cetinkaya, the new central bank authorities have bowed to the President’s pressure by cutting the interest rates (even below running inflation) to once again let the economy run hot.

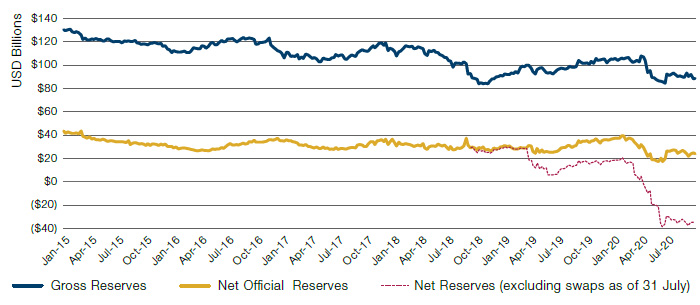

This combination of low real interest rates, credit expansion and a worsening balance of payments has put further pressure on the lira. In early 2019, the CBRT began to sell US dollars on the open market to prevent lira weakness. However, due to limited dollar reserves, open market selling became an off-balance sheet operation with local banks: the CBRT would take dollar deposits from banks, and in return, providing a swap agreement to sell it back to them in the future.

The CBRT’s net reserve (i.e. excluding bilateral swaps from official net reserves) stands at around -USD35 billion (Figure 5). As of the end of July, bilateral swaps stood at USD53 billion. Of that, USD1 billion are swaps from China and USD15 billion from Qatar. The remaining USD37 billion are dollars borrowed from local banks, which historically had been lent out abroad.

Figure 5. CBRT Reserves

Source: CBRT, Bloomberg; as of 28 August 2020.

Covid-19 and Tourism in Turkey

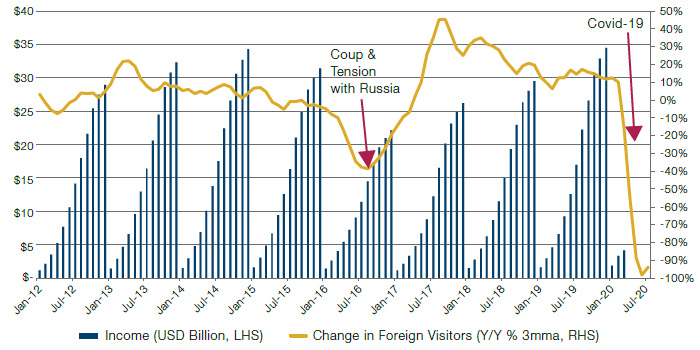

Prior to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, Turkey was a top tourist destination for its European, Russian and Middle Eastern neighbours. In 2019 alone, more than 45 million foreign nationals visited Turkey. The high season begins in May and ends in October, when foreign arrivals can reach up to 6-7 million per month. With the exception of 2016 (when the coup was staged and tensions with Russia caused a sharp decline in arrivals), Turkey has had more than 30million visitors per year over the last decade, which has represented a large source of hard currency income. In 2019, income from tourism totaled more than USD34 billion, with an average USD30 billion per annum over the last three years (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Tourist Income Versus Foreign Visitors

Source: Turkish Statistical Institute, Haver; as of July 2020.

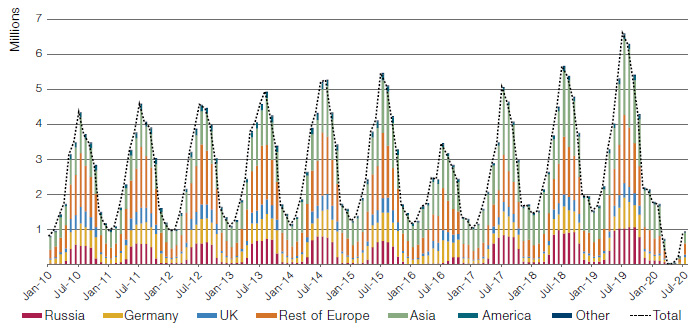

The first documented case of Covid-19 in Turkey was reported in March. As a result, the central government implemented broad lockdowns from mid-March to mid-May to control the spread of the virus. This lockdown, coupled with the increases of cases in Europe and Russia, has impacted the flow of tourists to the country, which is down more than 90% compared with last year (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Monthly Foreign Visitors by Country of Origin

Source: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Haver; as of July 2020.

This slowdown can be verified by number of passengers arriving at Antalya International Airport (‘AYT’), which is an important hub for tourists who want to visit the coastline resorts.

The collapse in tourist revenues will exacerbate Turkey’s existing economic problems and further deplete foreign currency reserves – ultimately compounding the hole in which the Erdogan regime finds itself.

Turkish Foreign Policy in the 2010s

Turkey’s foreign policy further complicates the economic picture. It is currently involved in a dispute with Greece over access to mineral rights in the Aegean Sea, and a war against various factions in Syria with deteriorating relations with both NATO and Russia. To better understand Turkey’s foreign policy, it is worth looking back at the history of the Middle East. The US was actively involved in the Middle East in the 1960s and 1970s to stop the speared of communism during the Cold War and secure its oil resources in the region. Turkey was on the front line of this conflict, as the easternmost member of NATO.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early ’90s and US oil shale industry boom of 2000s, there was no reason for the US to stay in the Middle East, as it needed to reallocate its resources to combat an emerging China. The pull-out of the US from the Middle East, which the Arab spring was a consequence of, changed the power equilibrium in the region. Every country – from Iran and Saudi Arabia to Turkey – rushed to spread their influence in neighbouring countries. It is this period, after the end of the Cold War, which has dictated the current mode of Turkish foreign relations. Without the need for NATO to defend Turkey against potential Soviet encroachment, the main aim of Turkey’s foreign policy became the extraction concessions from the West, (either Europe or US), using various crises as leverage (i.e. the refugee crisis, the imprisonment of US pastor, its decision to purchase S-400 missiles from Russia, etc).

However, this approach has become less effective over time. Turkey’s policies in Egypt and Syria have backfired. For example, by supporting Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Turkey has clashed with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. By supporting the opposition in Syria, it has confronted the neighbouring Assad regime and, indirectly, Russia and Iran. Tensions with Greece, a long-time adversary, yet fellow NATO member, increase the perception that when the economic crisis comes for Turkey, it will have very few friends willing to assist it.

Conclusion: Winter Is Coming

As markets rattled in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Turkey reached out to other central banks, including the Federal Reserve, to request a dollar swap line to counterbalance its draining dollar reserves. Since there were real questions about the independence of the CBRT and Turkey’s alliance with the west, only Qatar was willing to extend an additional USD10 billion swap line.

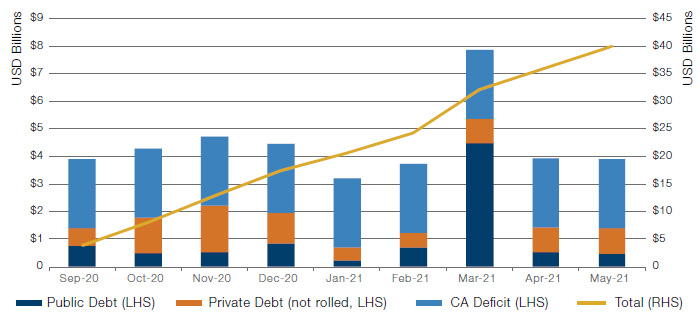

This, in combination with the tourism high season coming to an end, implies that hard currency inflows will be markedly lower than in 2019. All the while, Turkey’s account deficit has been widening.

Assuming a monthly current account deficit of USD2.5 billion for the remainder of 2020 (it averaged a USD7.5 billion deficit per month from April to the end of June), upcoming external debt servicing (principal and interest payments of public debt) and the portion of private debts that cannot be rolled (assuming a conservative 70% rollover ratio of private debt), Turkey needs more than USD30 billion of funding until the end of March 2021 (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Turkey’s External Financing Needs

Source: CBRT, as of May 2020; Haver, as of July 2020.

As a consequence, President Erdogan will need to make tough decisions in the coming months. He has previously publicly opposed asking for an IMF loan. Indeed, he has good reasons not to go to the IMF for any help: any IMF package would come with strict covenants. Not only would Turkey have to implement reforms, but it would also need to provide evidence and transparency into the state’s finances that these reforms were being enacted, conditions that are non-starters for President Erdogan’s administration.

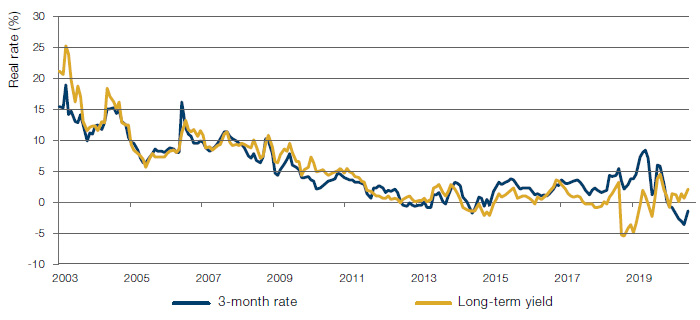

Nevertheless, the CBRT must either substantially increase interest rates to defend the lira by providing higher real rates (Figure 9) and slowing credit expansion, or impose restrictive capital controls. The former is likely to drive the economy to a recession and reverse the current account deficit. The latter would probably create a bank run as depositors would try to withdraw their dollar savings from the banking system.

Figure 9. Turkish Real Interest Rates

Source: Emerging Advisors Group; as of 19 August 2020.

Note: Real rate calculated using core CPI and Emerging Advisors Group estimates.

Neither option is easy for President Erdogan. He seems to have delayed the inevitable thus far, but time is running out. Before long, the country is likely to fall into a full balance-of-payment crisis.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.