Introduction

“[UK] living costs rising at their fastest rate for 30 years.”1 “UK is only major economy to put up taxes during cost-of-living crisis, research finds.”2 “UK wages fall at fastest rate since 2014 as cost-of-living squeeze bites.”3

The UK is set to experience a cost of-living crisis. But is everything lost for UK consumer spending?

As illustrated by these headlines, the UK is set to experience a cost-of-living crisis: many families were already expecting their monthly spend to go up in April, driven by an increase in National Insurance (‘NI’) contributions and an increase in the energy price cap. To put this in perspective, a UK consumer on 2021 median earnings of GBP31,000 was due to see NI contributions increase by more than GBP250 a year and energy prices rise by almost GBP700 a year (Figure 1).

And the Ukraine conflict is likely to push up living costs even further as the prices of fuel and other goods surge – think tank Resolution Foundation, for example, expects inflation (as measured by CPI) to hit 8.3% in the UK in April4, much higher than the Bank of England’s forecast of 7.25%.5

But is everything lost for UK consumer spending?

Figure 1. Energy Price Cap Rises by Almost GBP700 in UK

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Ofgem; as of 3 February 2022.

Household Budgets and Energy Costs

To answer that question, it’s first worth looking at the changes in income available for discretionary spend in UK households.

If we think of the typical UK consumer as a business, they operate roughly on a 40% margin – i.e., about 60% of household income is deducted in tax and fixed costs such as housing, food and bills; leaving 40% for discretionary spending.

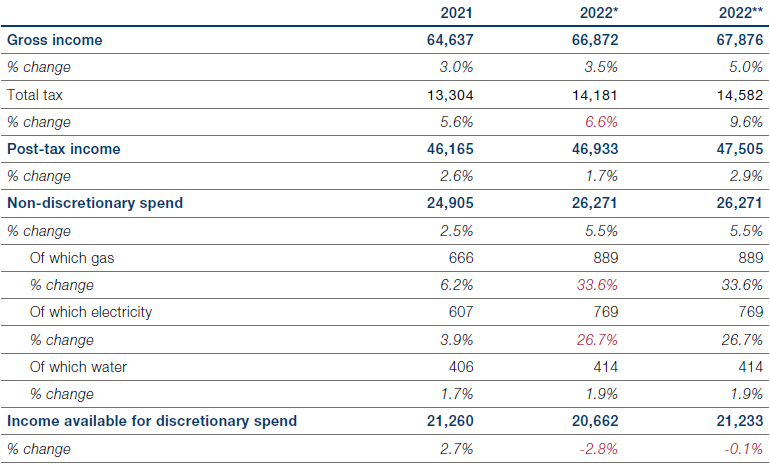

Figure 2 shows the effect of rising gas and electricity prices on the discretionary income available to the average UK household with a mortgage – a representation of some 27 million households. The first column is cash flow in 2021, while the middle column is the scenario at the start of 2022. At the start of 2022, we assumed that:

- Wages would increase slightly by 3.5%;

- Tax bills would increase by 6.6% (driven by an increase in NI contributions);

- There would be hefty increases in gas and electricity prices, soaring by 34% and 27%, respectively.

These changes resulted in the hypothetical UK household about 2.8% worse off in terms of discretionary spending in 2022 versus 2021.

Figure 2. Gross and Discretionary Income Based on Energy Price Rises

Source: Lazarus Partners, Man GLG; as of 15 March 2022. For illustrative purposes only.

Note: Hypothetical scenario of a UK household made up of 2.5 people and owning a mortgage.

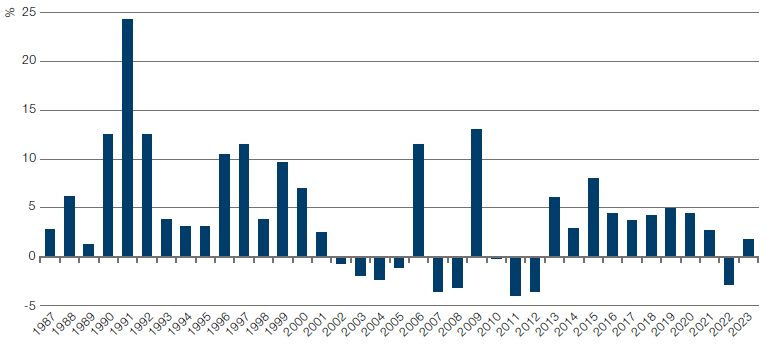

In historical terms, a 2.8% fall in discretionary incomes is not unprecedented (Figure 3). Larger annual falls occurred in the direct aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-8, and again in 2011-2, as rising commodity prices combined with stagnant or falling wages to produce sharp falls.

Figure 3. Annual Change in UK Discretionary Income

Source: Lazarus Partners; as of 31 December 2021.

However, all is not entirely lost.

Household Budgets and Wages

The third column in Figure 2 varies the assumptions made slightly at the beginning of the year, the most important being that we assume wage rises of 5% in 2022. In this scenario, the hypothetical UK household is not worse off in terms of discretionary spending in 2022 versus 2021.

It is not beyond the realms of possibility that this outcome occurs.

Supply and demand applies to the job market just as much as to commodities. Job vacancies stood at a record 1.3 million as of February 20226, which provides real impetus to wage growth. While over the long term, very few economists believe that wage growth can exceed 4%, in the short term, we believe it certainly can in short term. Indeed, average weekly earnings rose by almost 5% in January (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Average Weekly Earnings

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Office for National Statistics; as of January 2022.

The Stock of Money Supply

The level of money in the system is now so high that recession has become unlikely.

It is also worth mentioning here the stock of UK money supply. In 2020, monetary economists who pointed to the rapid growth of M4 were also correct in predicting the rapid recovery of the UK from its pandemic induced recession. M4 is a broad measure of the money supply, defined as a measure of notes and coins in circulation (‘M0’) as well as the money in bank accounts. Their argument was very simple: the rate of increase in the stock of UK’s money supply was such that it offset the deflationary effects of the lockdowns, and led to a rapid recovery from the economic damage. While the second derivative of M4 growth is now slowing, the overall stock of money in UK economy has never been higher (Figure 5). As such, our view is that the level of money in the system is now so high that recession has become unlikely.

Figure 5. UK M4

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Statista; as of December 2021.

Help From the Government

It is very likely that the government will step in to cap energy bills, picking up the excess themselves, rather than the alternative: a collapse in consumer spending and a deep recession.

Additionally, we are confident that the Covid-19 pandemic has changed the lens through which government sees its responsibilities. In 2020, expectations were that lockdowns would bring about a wave of joblessness. Instead, the British government introduced a furlough scheme, avoiding mass unemployment at the cost of billions of pounds.

In the same way, we doubt that the government will allow energy prices to completely dominate consumer spending. The pandemic has set the expectation that the government will intervene to manage the unmanageable consequences of economic crises. In our view, it is likely that the government will step in to cap energy bills, picking up the excess themselves, rather than the alternative: a collapse in consumer spending and a deep recession.

About 75% of UK gas is consumed between the colder months October and March, which gives policymakers around six months from now to organise a coping strategy. There are a number of different policy options: for example, we note that supermarkets are currently enjoying a 8.6% profit margin on unleaded petrol.7 It is not entirely impossible that the government could lean on major supermarkets to cut margins, or cut VAT themselves to ease the burden on consumers.

Conclusion

Headlines in the UK portray nothing but doom and gloom for the UK consumer (and thus the economy). However, scratch beneath the surface, and all is not lost. There are strong reasons for optimism: a reasonable chance of high wage growth to offset rising costs for consumers, a large stock of money supply and a government which is unlikely to stand idly if energy bills threaten to destroy consumer spending.

1. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-60390527

2. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/national-insurance-sunak-mcfadden-ifs-b2037508.html

3. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/mar/15/uk-unemployment-covid-inflation-wages-prices-energy-bills

4. https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/the-livingstandards-outlook-2022/

5. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-60197463

6. Source: ONS

7. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/supermarkets-accused-of-petrol-profiteering-as-oil-climbs-towards-100-a-barrel-rkxw328hh

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.