Introduction

It’s a typical Friday. You start off with a day in the office at a WeWork building, Google the nearest pub to meet for a pint after work, order an Uber home and maybe a takeaway delivered by Deliveroo for dinner before you start packing for your weekend away at an Airbnb apartment that you will drive to using your Zipcar rental.

These 2-sided networks – which connect a service provider (such as an Uber driver) to a customer (an Uber user) via a network (the Uber app) – are fast becoming ubiquitous in daily life. Their popularity has been driven by their ability to disrupt traditional marketplace structures and business practices, while replacing them with generally cheaper, better and more accessible services.

These new networks have been able to undercut incumbents because investors such as venture capitalists and private equity funds poured billions into start-ups, choosing to judge success by market share and scale as opposed to profits. However, WeWork’s failed initial public offering in 2019 and a focus on profits once again has forced venture capitalists to rein in their funding which has, in our view, created opportunities for long-short equity investors focused on these two-sided networks.

How then, should we pick future winners? We believe those firms whose networks rely on the sale of a directly comparable, easily costed service exist in a much tougher environment, often competing for users and contractors directly on price. In contrast, networks where users sell their data in exchange for a ‘free’ unique service and targeted adverts are able to impose much higher switching costs on users, compete on service rather than price, and in the long-run, best protect margins.

Types of Two-Sided Networks

It’s important to distinguish between the two different types of two-sided networks: the first is networks where buyers and sellers directly face each other in an obviously transactional relationship; and the second where buyers and sellers have no direct relationship at all, with each side instead only indirectly interacting/transacting through the platform itself.

For the former, we could re-use our Uber example, where drivers and customers are in direct contact, with a single, well-defined, easily replicable transaction occurring: buying a ride. Google would be an example of the latter, an asymmetric two-sided network. In this case, information seekers are the seller – they trade their data for a free, efficient search engine, with Google re-selling their data to advertisers, who pay for consumer access.

Networks in which buyers and sellers are not in direct contact often rely heavily on the quality of their network to attract custom, especially if they are free. Google competes for users based on the quality of its search engine. Facebook aims to create a critical mass of users, to the point where not having a Facebook profile creates social penalties. Match.com is an interesting hybrid – users have direct contact with each other with Match.com charging a fee, but the network competes heavily on the quality of user experience and, like Facebook, aims to generate a critical mass of high-quality users – in this case, dating partners – and unique experience.

The Dark Side of Two-Sided Networks

One fascinating fact about most of these two-sided networks is that they hold almost no fixed assets: Airbnb doesn’t own real estate, Uber owns almost no cars and Amazon has almost no stores. While this can create very businesses with high return on capital employed (‘ROCE’), it also provides a challenge to long-short investors who are trying to value these companies as it means that there are very low barriers to both entry and exit of participants.

A combination of these low barriers to entry and investor willingness to look past losses over market share have resulted in intense competition and low switching costs. A prime example is the ride-hailing market: there are almost no penalties to switching between platforms, which has significantly dented the profitability of major providers. A consumer can compare prices between Uber, Lyft and other ride hailing start-ups, and simply pick the cheapest one. The situation is exactly the same for drivers, who can choose the app that offers them the biggest percentage of commission, which also shifts liquidity around. Uber’s early work in developing the market in London can be picked off by Kapten, Bolt and Ola, which tap into the same drivers and consumers. The long-term winner will be the one who can deliver a high-quality service at the right price elasticity point, while still generating positive contribution margins.

Another new important consideration is the risk of a two-sided network to antitrust action. Some networks have achieved such a dominant position that they are in danger of antitrust action to reduce their activities. US Democratic Presidential candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren has been vocal in calling for the break-up of big tech – indeed her campaign team have gone so far as to publish a blueprint for how it can be done.1

Regulatory challenges are also a worry. The EU’s Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager fined Google EUR4.3 billion in July 2018 for using Android to “illegally cement its dominant position” and forced it to make changes to its AdSense search.2 Vestager has admitted that this has not changed market dynamics, more stringent European data regulation could prove a stumbling block for otherwise dominant networks3, and could be a potential cause of antitrust action. Elsewhere, Uber’s licence to operate in London has been revoked after Transport for London found instances of driver’s faking their identity.4 One should note, however, that increased online regulation does not always result in detrimental impacts to incumbents – as seen with the General Data Protection Regulation (‘GDPR’) in Europe. Indeed, many industry participants would say that incumbents were better placed to deal with the changes, which ultimately resulted in a further widening of their competitive moats.

Whilst these judgments have been contested, they do pose the possibility that greater regulatory oversight will affect revenues in the future. However, what is not being discussed is how this will force the industry to change in terms of M&A activity. Acquisitions have been these networks’ sincerest form of flattery, with incumbents often buying serious rivals in order to consolidate their position: think Facebook buying Instagram or Google buying Youtube. In our view, the current political environment may make it harder for companies to buy growth in a similar manner.

Finally, as investors become wary about ploughing money into loss-making operations and the spigot is turned off in both public and private markets, consumers are likely to see price rises – from ride-sharing to food delivery – that pinch their spending power. It will be telling to see where the true demand-elasticity volume is when subsidies are eliminated. Private companies may be able to stave off the price rises a little longer than the public companies, but this provides another significant opportunity for long-short equity investors, in our view.

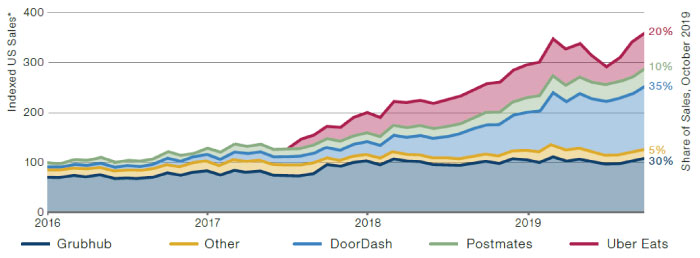

Figure 1. Incumbents Overwhelmed: US Meal Delivery Monthly Sales

Source: Second Measure; as of 23 January 2020. *Indexed to meal delivery January 2016 sales (=100). Note: Uber Eats’ sales indistinguishable from Uber rides before August 2017. Some sales indistinguishable from May to August 2019; Other - Eat24 (prior to October 2017 acquisition), Caviar, Waitr, Amazon Restaurants (prior to June 2019 closure).

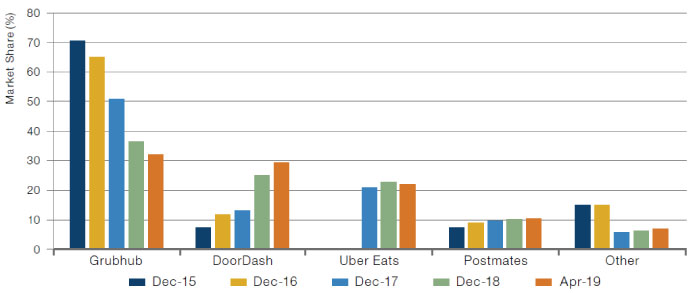

Figure 2. US Market Share, Online Meal Platforms

Source: Exane, as of January 2020.

Upfront Costs Versus Free Services

In our view, the key metric for the success of a tech firm is whether consumers are aware of the transaction that is taking place. If the transaction is obvious and has an upfront cost, challengers can compete on price to attract consumers and contractors. However, if the service is ‘free’, customers are less inclined to shop around, and instead stick to the provider with the smoothest service, to the massive advantage of incumbents. When thinking about two-sided networks, we believe investors should look for firms whose customers don’t even realise they are paying.

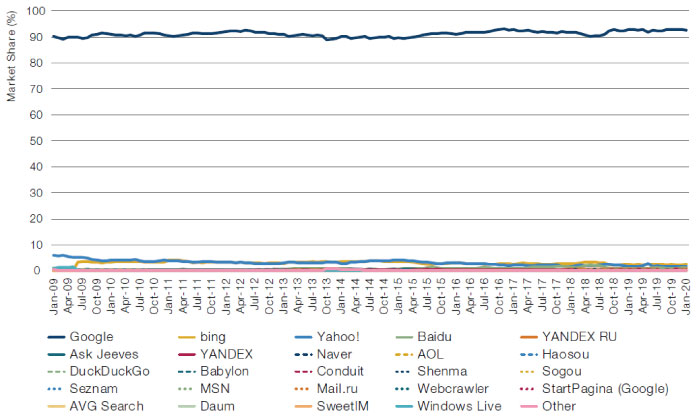

Figure 3. Search Engine Market Share - Worldwide

Source: Statcounter; as of 31 January 2020.

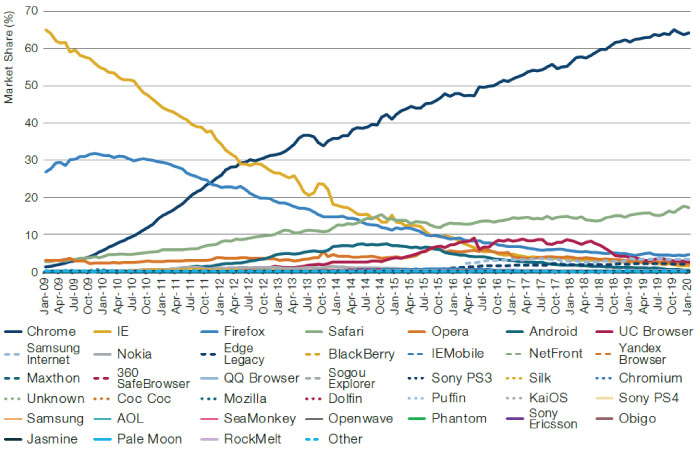

Figure 4. Browser Market Share – Worldwide

Source: Statcounter; as of 31 January 2020.

Take the issue of switching costs, for example: if the benefits of the network are not easily replicable, switching costs become prohibitive. Whilst product sellers could move away from dominant online marketplaces, companies such as Amazon and Alibaba retain the status of ‘premier’ online brands in the minds of consumers, enabling them to obtain a larger share of online eyeballs. This incentivises sellers to continue using the platforms based on the high amount of buyers coming to the platform, and creates a virtuous cycle: more sellers means a better choice of products at better prices, which attracts more customers, and so on.

The same is true for social networks. Whilst one can start a new network site any time, it is very difficult to encourage hundreds of friends and family to adopt it all at once. This means that anyone seeking to move faces some form of penalty. Successful new social networks thus tend to compete by offering something new: in the case of Instagram, it offers a better site to host visual content, Twitter offers users the chance to proclaim their thoughts to the world with no filter, TikTok offers entertaining free short-form video. Neither was in direct competition with Facebook in terms of the user experience (unlike MySpace). In addition, such social networks as Facebook have been very adept at creating artificial barriers to switching – by encouraging you to employ your log-in to subscribe to other sites, for instance.

When switching costs apply, competitors face a commensurately larger challenge in such scenarios, making their moats that much larger. This should, in turn, affect investors’ valuations of the company in question. In our view, the question should be less about how quickly a site can gain users, and – after a while – more about how well it can hold onto them and the overall replicability of the product offering.

An analysis of two-sided networks as a revenue driver is also key to understanding the potential impact of antitrust drives. Current US legislation is focused on protecting consumers from harmful price increases, rather than being necessarily focused on industry share. It is therefore difficult to see how this could apply to networks where the product is essentially free. For example, if an online retailer drives down prices for consumers, it is hard to see how a case of consumer harm could be established in court. Likewise, search engines which are free could similarly avoid such legislation.

Conclusion

The environment that these two-sided network companies find themselves in is dictated by three factors. The first is that most of these companies are asset-light, resulting in low barriers to entry and leaving them reliant on the quality of their two-sided network for survival. Secondly, competition is fierce: not only is there no loyalty (from either the consumer or contractors), but also, with huge amounts of cheap capital available to private firms, listed companies are challenged by private firms whose only concern is market share at the expense of profit. Without assets and in a cutthroat environment, firms are also subject to increased regulatory scrutiny, making growth via M&A less feasible than it was during the 2010s.

While it may feel like the magic and sparkle is wearing off in these networks, we believe these developments are actually helping separate the wheat from the chaff and will thus provide ample investment opportunities for long-short equity investors. The rising-tide-lifting-all-boats scenario that we have seen in the last couple of years may now be ebbing, making stock-picking ever more important.

1. Medium, Here’s How We Can Break Up Big Tech, 8 March 2019.

2. Sky News, EU Competition Chief Struggles to Tame 'Dark Side' of Big Tech Despite Record Fines, 23 December 2019.

3. Financial Times, EU Puts Big Tech Under the Spotlight, 2 December 2019.

4. The Guardian, Uber loses London Licence After TfL Finds Drivers Faked Identity, 25 November 2019.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.