Introduction

When congratulated on Napoleon’s success on the day he was crowned emperor, his mother, Letitzia Bonaparte, famously replied: “Pourvu que ça dure.”

Let’s hope it lasts.

The same could be said for today’s market. For the past year, the only game in town has been a surging reflation trade, as equity markets have rallied from their post-pandemic lows. Combined with unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus, nearly all asset classes have moved away from simple reflation and are now pricing in a more normal level of inflation than we have experienced for the last decade or so. The one asset class that isn’t pricing in inflation is government bonds. Indeed, in some ways this is worse, as it means bonds are just as, if not more, expensive than the other asset classes.

But rising prices mask a deep fragility. We may be approaching ‘peak policy’, as governments and central banks, faced with prospect of rising inflation, slow the pace of monetary and fiscal stimulus. Once the money presses stop printing, markets may have to face reality: a global economy propped up on an unprecedented mountain of debt, with asset prices at eye-wateringly expensive levels and in danger of a selloff.

Timing market peaks can often be a futile exercise. In this instance, the likeliest catalyst for a selloff is a change in the narrative around inflation. The consensus of both the market and central banks is that inflation is transitory rather than persistent. If this proves to be wrong, and real rates do indeed need to rise, the current situation presents a highly unusual risk to the downside. Rather than trying to pinpoint a moment in time when the storm will break, prudent risk committees need to envisage how portfolios are positioned in advance. Absent a sentiment change, we could experience a volatile summer of hesitation. But investors need to keep one eye firmly on the weather gauge: if the consensus on inflation starts to move, they will need to move equally quickly.

Let’s hope that the reflation lasts and rates stay low, then. After all, Napoleon ruled as Emperor of France for almost a decade after Madame Mère’s words. But all bull markets eventually meet their Waterloo, and the discrepancy between asset prices and the real economy is now so large that if this one breaks, we won’t be quoting any of the Bonapartes. Instead we’ll all be quoting the word of Pierre Cambronne.

Ignore Bonds: Reflation, Administered Prices and Peak Policy

The story of the past year can be captured in one word: reflation.

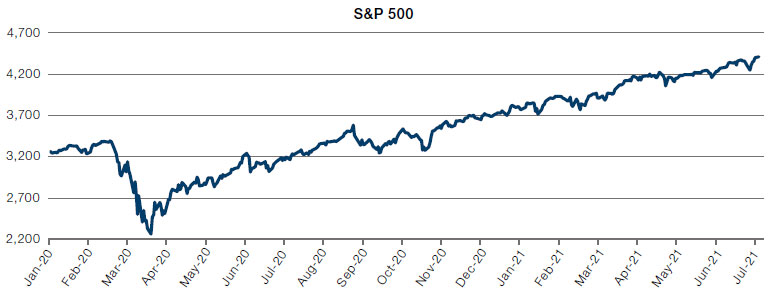

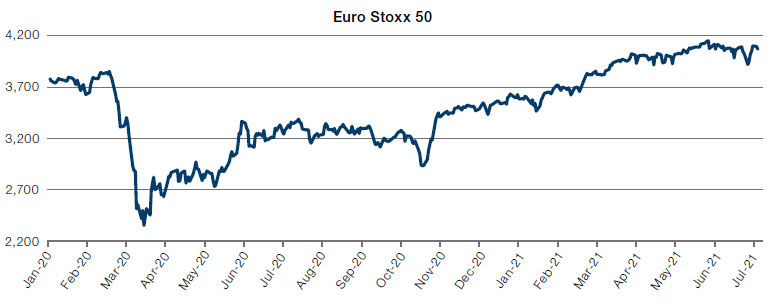

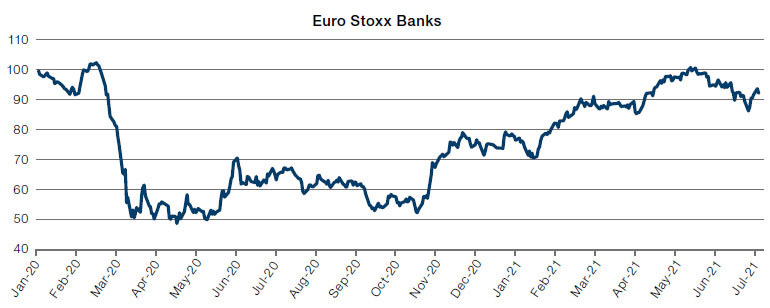

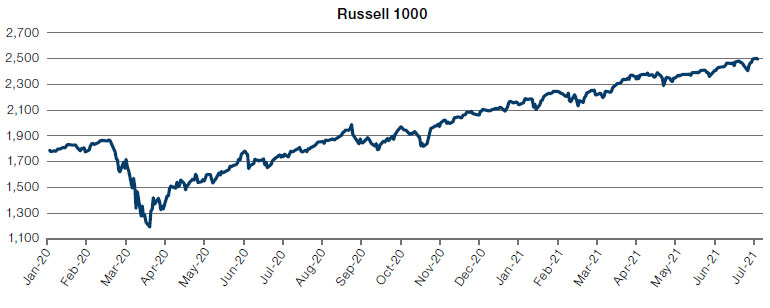

The story of the past year can be captured in one word: reflation. If we look at the prices of equities and commodities classes, it is clear that they have rallied in the expected manner, recovering from the depths of coronavirus induced deflation, moving through a reflation and now reflect the newly inflationary environment of 2021. From the March 2020 lows, the Euro Stoxx 50 Index is up 72%, the S&P 500 Index around 90% and the Russell 1000 Index is up a staggering 96%. The European Banks Index – a sector which is very cyclical – is up 96% as well (Figure 1). In commodities the picture is similar, with the iShares Diversified Commodities ETF up 56% over the same period (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Selected Equity Indices

Source: Bloomberg; as of 27 July 2021.

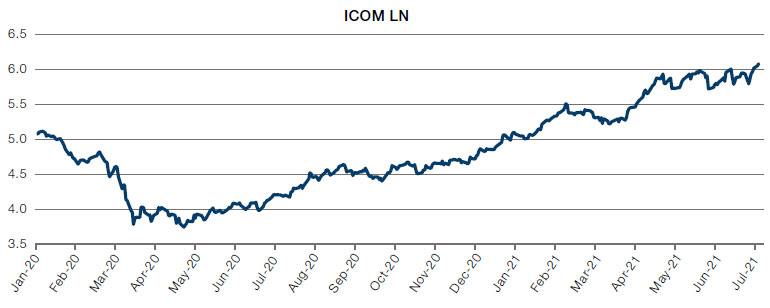

Figure 2. iShares Diversified Commodities ETF

Source: Bloomberg; as of 27 July 2021.

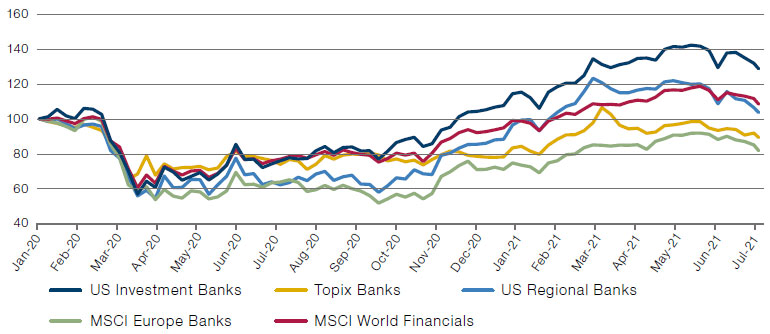

The traditional method of playing a reflation trade was through bank stocks, the sector with possibly the greatest exposure to the economic cycle. Since the reflation began in earnest, the rising tide has lifted almost all the banks together (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Banks Indices

Source: Bloomberg; as of 20 July 2021.

Rebased to 100 as of 1 January 2020.

Inflation numbers keep rising but asset prices are no longer shooting up quite so fast.

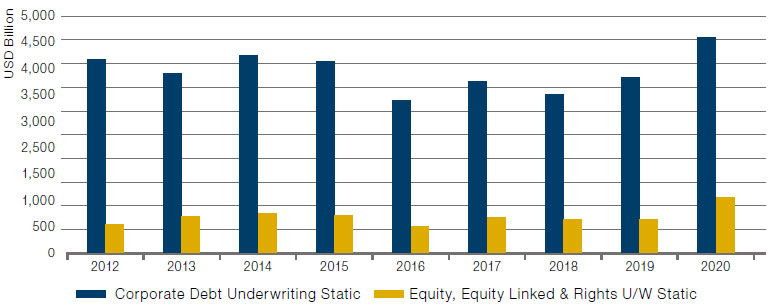

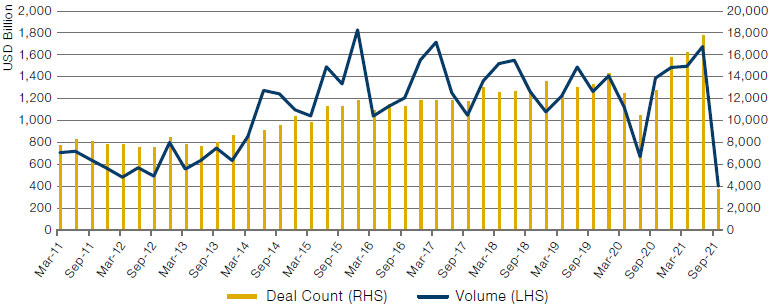

Part of the reason for the impressive outperformance of banks over the last six months or so is the uplift they have received from the provisions made for Covid-related losses. Nearly all banks made generous provisions, but since most governments reacted to the crisis with alacrity, very few of the provisions needed to be utilised. Instead, banks have been able to remove the provisions from their balance sheets, freeing up capital and boosting their equity value. In addition, we seem to have gone through an investment banking supercycle. Debt and equity underwriting, and M&A activity, are above long-term averages, and are expected increase significantly in both the US and Europe (Figures 4-5). However, the boost provided by over-generous provisions cannot last forever, and bank momentum appears to be stalling, along with the reflation trade itself; inflation numbers keep rising but asset prices are no longer shooting up quite so fast.

Figure 4. Debt and Equity Underwriting Activity

Source: Bloomberg; as of 7 June 2021.

Figure 5. Global M&A Activity

Source: Bloomberg; as of 20 July 2021.

The move from reflation to higher inflation would normally be reflected in higher bond yields. This has not been the case: the US 10-year yield has stubbornly stayed below 1.8%, despite having had US CPI prints of 4.2%, 5% and 5.4% in April, May and June, respectively. In contrast, in March 2019, 10-year yields were at 2.5%. Even when allowing for the base effect, the yields don’t reflect the increased levels of inflation or the expected economic growth from government stimulus.

Figure 6. US 10-Year Yield

Source: Bloomberg; as of 27 July 2021.

Why then, have yields not moved?

In short, it’s the Federal Reserve’s fault.

Why then, have yields not moved?

In short, it’s the Federal Reserve’s fault. After a year of unprecedented stimulus, the Fed’s purchasing now exceeds the issuance from the US Treasury. With such a strong bid in the market, it is not surprising that yields have not gone higher. Indeed, with the US 10-year yield at 1.12% and the Fed purchasing USD120 billion of assets per month, it is hard not to conclude that we now live in a world of central bank-administered prices. The same is true in Europe, where the European Central Bank is buying EUR20 billion per month. Both central banks have been responsible for contributing to low yields and high asset prices, by crowding out normal investors with their purchasing programmes. This has in turn created a global savings glut, which for want of anywhere else to go, both supports bond prices as well as riskier assets. Indeed, the situation is likely to get worse. The ECB has changed its own mandate, with a 2% inflation target allowing for overshoots replacing the previous target of below but close to 2%. In the short term, this reinforces the structural dovish stance of the ECB and is bullish for European assets. But it will also continue to keep US yields low. European savers are unlikely to find any yield at all in the new environment, and to do so will either have to move to riskier European assets or buy US Treasuries.

In addition to the monetary stimulus, we have had unprecedented fiscal stimulus. The American Rescue Plan Act will provide USD1.9 trillion in fiscal spending to the US economy, with an additional infrastructure deal to be signed during the summer. Likewise, the EU has boldly gone where it dared not go before, and created the EUR750 billion NextGenerationEU recovery package, in which the bloc acted as a borrower for the first time.

In this environment, it is hardly surprising that 10-year breakeven inflation rates are shooting up. Having troughed in March 2020, they are now above 2%, driving the reflation trade.

Figure 7. US 10-Year Inflation Breakeven Versus US 10-Year Yield

Source: Bloomberg; as of 27 July 2021.

While this reflation trade has so far been supported by the combination of monetary and fiscal stimulus, it is likely that at some point this summer we reach peak policy. During the Fed’s Monetary Policy Committee meeting, both rates and assets purchases were held steady. However, if above-expected inflation continues to persist and the job recovery continues, it is likely that the Fed will exceed its four policy goals of: measured inflation that averages 2%, long-term inflation expectations well-anchored at 2%, maximum ‘inclusive’ employment and smoothly functioning credit markets. These criteria are designed to leave maximum wiggle room, with the Fed not strictly defining whose inflation expectations are important nor how maximum inclusive employment differs to maximum employment. But even with the wiggle room, policymakers are now “talking about talking about tapering”.1

In our view, three of the four goals have already been achieved. The only one which has yet to fully recover is employment, and on current trajectories, maximum employment may well be reached before Christmas. If this momentum persists, the Fed may have to seriously start talking about tapering around the Jackson Hole Symposium in late August – which would be in line with market expectations.

The Fed may have to seriously start talking about tapering around the Jackson Hole Symposium in late August – which would be in line with market expectations.

That discussions of tapering are not occurring is not a surprise: what did take the market by surprise was the move of in the dot plot, which indicated that MPC members now regarded 2023 as a likely year for rate hikes. Whether or not the Fed has blinked is open to debate. What is more certain, however, is that the Fed is not seriously considering extending further monetary policy support – no Fed board member is talking about talking about further loosening. Since the market has already absorbed and priced in the Fed’s existing purchasing, the risks are to the downside: we have probably reached peak policy from a monetary stimulus standpoint, and after the move in the dot plot, investors will be watching every Fed statement like hawks for signs that tapering is moving closer. If the infrastructure bill is finalised (and as ‘ifs’ go, it is an expensive one, at an estimated USD1.2 trillion, watered down from USD2 trillion), it is likely that political capital for further fiscal stimulus will be exhausted. Once markets start to price this in, we could well have reached peak fiscal policy by the end of summer too.

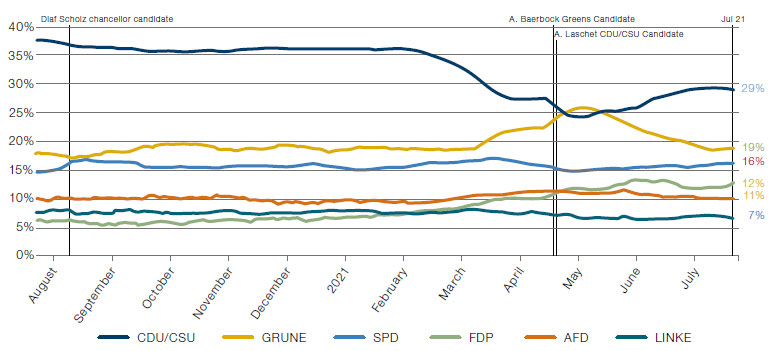

The situation is similar in Europe. The ‘NextGenerationEU’ package took around six months to approve, and barely scraped past the vetoes of both Poland and Hungary. There is almost no likelihood of further fiscal stimulus during the summer, although the German elections in September 2021 may provide a catalyst for change. Steady polling improvements by the Green Party may mean that they replace the Social Democrats as the coalition partners for Chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU – or indeed perform well enough to rule outright. The Greens slightly improved their performance in the 6 June election in Saxony-Anhalt with 6% of the vote, a CDU stronghold. They now sit on 19% of the vote in national polling (Figure 8). If the Greens do enter coalition, we would expect them to drag Germany towards a more expansive fiscal policy stance, both at the domestic and at the European level. If the Greens don’t make the coalition, however, the CDU will be under much less pressure to continue their move towards a higher level of fiscal spending, and could well return to the austerity-first policies we have seen for the last decade. In our view, this would leave the EU, along with the US, either at peak policy or perilously close to it.

Figure 8. German 2021 General Election – Poll of Polls

Source: Politico; as of 21 July 2021.

Central Banking With Chinese Characteristics

With the Fed happy to let inflation run hot, it is instructive to contrast the Fed’s approach with the one being taken by the People’s Bank of China.

There is also something deeply troubling about having the two largest economies in the world being managed with such a difference in the assessment of where the risk lies.

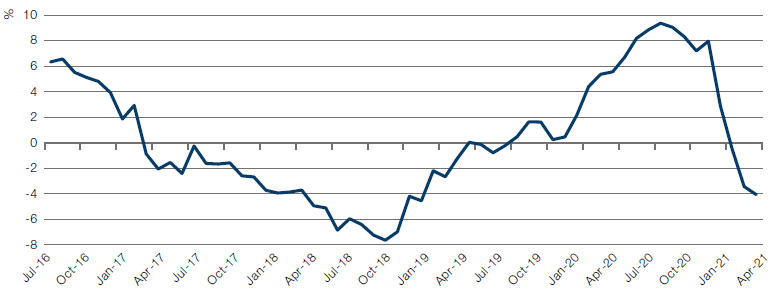

There has been a slowdown in the growth of the Chinese credit impulse, indicating that the PBOC is reducing the amount of stimulus within the Chinese economy (Figure 9). Indeed, it is around seven months since Chinese credit creation peaked. Likewise, the yuan has been allowed to appreciate, acting as a further drag on exuberance by discouraging overseas investment. In our view, it is possible to conclude that we are seeing two very different approaches to tackling the recovery: one which believes that inflation is transitory, the other which is treating it as a serious concern. The inflation unleashed by the Fed has caused sharp increases in commodity prices. This damages the Chinese economy more than most, given China’s reliance on commodity imports, particularly copper.

Whilst the PBOC is not exactly hawkish, having just instituted a 50bps cut in the reserve requirements for Chinese banks, it is noticeably less keen to flood the market with liquidity than its western counterparts. Time will tell who has taken the correct approach to managing their economy, but from a market perspective, it reinforces that we are about to reach peak policy. There is also something deeply troubling about having the two largest economies in the world being managed with such a difference in the assessment of where the risk lies.

Figure 9. Chinese Credit Impulse

Source: Bloomberg; as of 20 July 2021.

The Downside

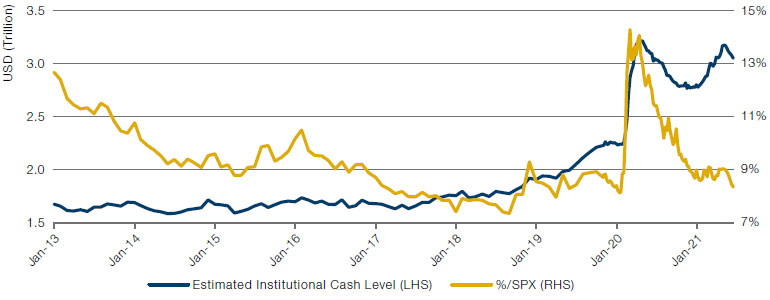

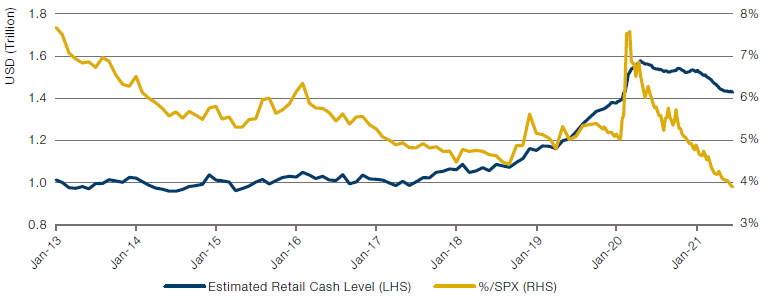

As investors sense that further policy support may well not be forthcoming, the reflation trade is slowing down. This is reflected in the size of dry powder waiting on the sidelines: institutional investors have stockpiled around USD300 billion of cash since the turn of the year, indicating their unwillingness to keep buying into the reflation (Figure 10). Conversely, it seems that retail buyers are all in, increasing their exposure as the meme stock ride continues (Figure 11).

Figure 10. Estimated Institutional Cash Level

Source: ICI, UBS; as of 14 July 2021.

Figure 11. Estimated Retail Cash Level

Source: ICI UBS; as of 14 July 2021.

Institutional investors are right to be wary. In our view, there are two threats for risk committees to be aware of. The short-term risk can be summarised as confounding consensus. Instead of a goldilocks scenario of strong growth, transitory inflation and yields under control, it would not take much for the narrative to change to a jeremiad of peak policy and sticky inflation, particularly in the context of a rising oil price. We tend towards the latter view: inflation may well be more persistent than central banks and the market think. All this could come at a time when growth is likely to plateau, or at least the second derivative of growth is fading. This, in turn, raises the prospect that the market could start talking about stagflation. The overwhelming consensus these days is that the market is awfully expensive, but with so much liquidity around one should still be very long. Obviously everyone is convinced they will sell right on time to avoid a potential Waterloo. However, it rarely works that smoothly in practice.

It is accelerating (rather than simply persistent) inflation, sustained over the medium term, which currently represents the greatest threat to asset prices.

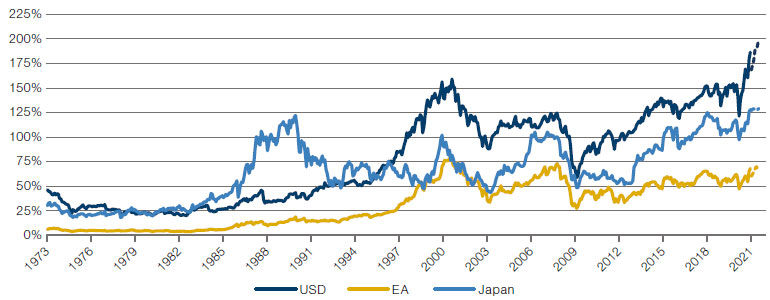

Beyond that, the medium-term risk isn’t just sticky inflation, but accelerating inflation which central banks struggle to control. It is accelerating (rather than simply persistent) inflation, sustained over the medium term, which currently represents the greatest threat to asset prices. During periods of accelerating inflation, market cap to GDP is significantly lower than the levels we currently enjoy (Figure 12). At the end of 2020, the US market cap-to-GDP ratio stood at 186%. It is currently estimated to have reached 200%. In the 1970s-80s, the last time the US experienced sustained inflation, this ratio never exceeded 50%. The situation is less dire in Europe and Japan, although the Japanese ratio is still higher than during the bubble of the late 1980s.

This is not to say the situation in 2021 is perfectly analogous. The bargaining power of labour is far less than it was during the 1970s: for a long period of accelerating inflation, wages need to continually rise to meet increased prices, something which is not a given without highly unionised workforces. But even without the spectre of overmighty union barons, it is difficult to argue that inflation does not destroy equity value and supress prices. As such, when the destructive effect of a move in inflation can be so large, a small change in the market’s estimate of the probability of sustained inflation will likely be able to move prices down substantially.

Figure 12. Market Cap to GDP - US, Europe, Japan

Source: Goldman Sachs; as of 13 July 2021.

One doesn’t have to be a genius to do the maths. Given the exceptionally extended level of equity valuations in the US, if inflation persists throughout the summer and autumn, we will be facing a difficult risk management challenge.

We believe the highly uncertain nature of the current environment, combined with the unprecedented level of debt everywhere, justifies a probability weighted approach to different market scenarios and economic paths. Small changes in the market participants’ perceptions of probability distribution might generate unusual price moves.

Conclusion

Without a change in the narrative, however, markets will likely continue grinding up regardless. Given the potential size of a correction, pourvu que ça dure. Let’s hope the bull market lasts.

Since the nadir of the coronacrisis, a surging reflation has lifted almost all asset classes and provided respite for hard-pressed asset managers.

However, the easy money from the reflation trade has now been made. The threat of inflation seriously endangers the low real rates that asset prices have become reliant upon. Given how expensive prices have become, we run the real risk of a major correction if the consensus narrative on inflation changes from transitory to persistent, and we continue to see inflation accelerating.

Other scenarios are possible, of course. However, if this one occurs, or if the probability of it increases, portfolios will need to be adjusted away from those assets most at risk from inflation: US equities (particularly Growth stocks) and government bonds. As always when markets get risky, it is worth considering the role of active management, and adding to allocations to hedge funds to provide a degree of risk protection.

Without a change in the narrative, however, markets will likely continue grinding up regardless. Given the potential size of a correction, pourvu que ça dure. Let’s hope the bull market lasts.

1. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-fed-daly-idUSKCN2D62LR

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.