A version of this article was originally published in Trustnet on 17 May 2022.

“If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

– Often attributed to Henry Ford

Introduction

Conventional thinking can sometimes become so ingrained that it is difficult to imagine anything outside its borders. Consider the S&P 500 Index, one of the most-watched financial markets, and perhaps the best-known barometer of investors’ wealth. The S&P 500 returned 27% in 2021, a full 17% ahead of its 30-year average.

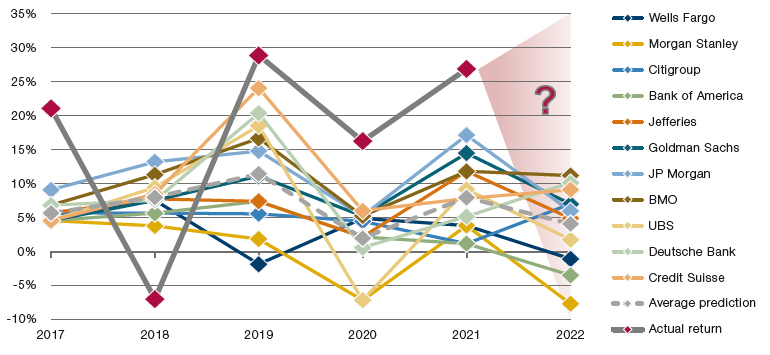

It is clearly a worthwhile exercise to predict such performance and allocate capital accordingly. Indeed, analysts from investment banks – arguably some of the bestinformed market participants around – duly make their predictions on an annual basis. According to Bloomberg, only one got within 10% of the S&P’s actual return in 2021. On average, the cohort was out by 19%, and the worst by 26%. What’s more, when you look back historically, as we do in Figure 1, 2021 was not an unusual year: it seems that even these best-informed analysts are unable to forecast the returns of arguably the most-watched financial market.

Figure 1. 12-Month Ahead Return Forecasts of the S&P 500 by Bank Analysts

Source: Man Group, Refinitiv; as of 31 January 2022.

The organisations mentioned are for reference purposes only. The content of this material should not be construed as a recommendation for their purchase or sale.

Thinking Outside the Box

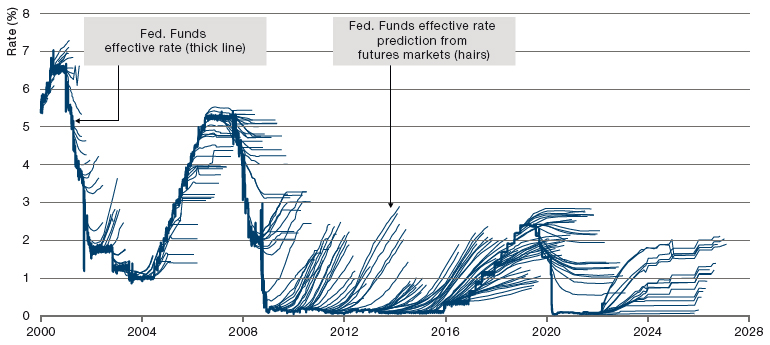

Does this matter? Well, yes it does. If you can genuinely say that you can predict the returns of the S&P 500, please get in touch. For the rest of us, the unreliability of return predictions means we are liable to mis-allocate resources. Further, if Figure 2 is any guide, there is scant evidence that the crystal ball works any better in rates markets.

Figure 2. Federal Funds Effective Rate Versus Expectations From Federal Funds Futures Markets

Source: Bloomberg, Man Group; as of 28 February 2022.

One answer might be to attempt to generate better predictions. Given evidence from Figures 1 and 2, however, we might argue that this is the equivalent of asking Henry Ford for faster horses. Instead, we believe there is an alternative route to generating better returns; by abandoning horses – and return forecasting – altogether.

Heresy?

It may sound counter-intuitive that better returns can be achieved through abandoning return forecasting. Step back, however, and think about the bigger picture of what we are trying to do. Ultimately, we want to generate a better return on our capital, but our key point would be that we should not do this without factoring in risk. We might not, for example, invest the same amount in two asset classes whose return estimates were the same, but whose risks are quite different. Common sense suggests investing more capital to the asset with lower risk, all things equal. Risk-adjusted returns, therefore, would seem to be our primary goal when constructing portfolios.

You Can’t Eat Sharpe Ratio

Our astute reader will, no doubt, point out that in the real world, it is often the absolute return that matters, and not the risk-adjusted return. Who cares if a 2% return is achieved with an information ratio (return/risk) of 3, when a return of 6% is required to meet liabilities?

Faced with this problem, it seems natural that investors seek better returns through taking more risk. This may mean allocating more to equities than bonds, or more high-yield over investment-grade credit, for example. This problem is exacerbated, of course, the lower interest-rates become; indeed, this has been the narrative for most of the last three decades.

Leverage to the Rescue

So, it would seem that the real world (the desire for an absolute return) gets in the way of what is optimal from a capital allocation point-of-view (maximising risk-adjusted returns). However, this problem is fairly easily solved with a little leverage. Either by investing in marginable instruments (futures over cash, for example), or borrowing to fund cash positions, higher returns can potentially be generated from investments with high risk-adjusted returns. From our example in this section, we can turn a 2% return into a 6% return by gearing three times, and still with an information ratio of 1. Leverage is often viewed in a negative light, but, when the risks are properly understood it should not have to be this way, in our view (see ‘Leverage Does Not Equal Risk’ for further reading).

Is Risk Predictable?

We finish this article where we started, by looking at predictions, but this time through the lens of risk. Risk-adjusted returns can be maximised, either through improving return predictions (which we would all agree is hard), or by improving risk predictions. It stands to reason that if we predict that risk is likely to decline or stay low, we should allocate more capital to it, all things equal.

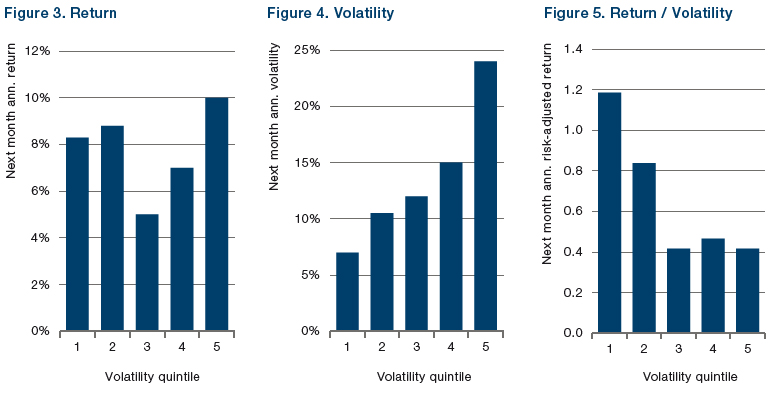

In Figures 3-5, we reproduce some key charts from Harvey et. al. (2018). Figure 3 is their version of our Figure 1, namely that the equity return this month is a poor predictor of equity return in the following month. In Figure 4, on the other hand, the authors show that volatility this month is a good predictor of volatility in the following month; if volatility this month is low (high), it is likely that volatility next month is also low (high). All things equal, therefore, risk-adjusted returns are likely to be higher when risk is low than when risk is high (Figure 5). It is comforting to know that we should put more money to work in the good times, and take money off the table in the bad. This should help us sleep better at night.

Source: Harvey et. al. (2018).

None of this should be new to alternatives investors. What we are describing is volatility scaling. This, and the principle of using leverage to gear up strategies with low returns but high risk-adjusted returns, have formed the basis of portfolio construction in systematic alternatives strategies for decades.

Conclusion

We don’t need to predict returns with greater accuracy to generate better returns from portfolios. Investors can additionally look at the predictability of risk, and make use of leverage to gear up investments with low returns yet high risk-adjusted returns.

In a nutshell, what we are saying is that returns are hard to predict, but we don’t need to predict returns with greater accuracy to generate better returns from portfolios. Investors can additionally look at the predictability of risk, and make use of leverage to gear up investments with low returns yet high risk-adjusted returns.

Focusing on risk also lends itself to a systematic approach. Risk metrics – such as volatility – are readily calculable and backtestable, unlike predictions of the S&P 500 from analysts. Indeed, human behaviour is rarely as reliable as such metrics. What if the analyst at the bank making that prediction changes? How does the analyst’s view alter with prevailing market sentiment? How many coffees did the analyst have before registering a prediction?

Behavioural finance teaches us that, when it comes to making investment decisions, human beings are often ill-equipped because of our emotions. Perhaps it’s time to embrace this and accept our failings.

It may be time to not just back another horse, but choose a different race altogether.

Bibliography

Harvey, C. R., Hoyle, E., Korgaonkar, R., Rattray, S., Sargaison, M., and Van Hemert, O. (2018); “The impact of volatility targeting”; Journal of Portfolio Management, 45(1), 14-33.

Abou Zeid, T. (2022); "Leverage Does Not Equal Risk”.

The author wishes to thank Andre Rzym for his contribution of Figure 2.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.