Introduction

They were the worst of times. And then suddenly they were the best of times.

The unprecedented market dislocation during the first half of 2020 spurred significant interest in the distressed credit asset class from capital allocators. All over the world, governments and companies were borrowing like never before to stave off the effects of the demand slump brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. Conditions were ripe for a distressed debt bonanza. And then, all of a sudden, markets bounced back. Credit spreads dropped, and it was as if the pandemic had never happened. Allocators put their cheque books away, thinking that they had missed the party before they’d had a chance to knock back their first drink.

While the popular conception of distressed debt in 2020 might run along these lines, the description above is a caricature that belies some key tenets of what good distressed credit investing should look like. Instead, we posit that distressed credit is inherently opportunistic, with an expanded opportunity set during periods of market dislocation. But trying to time asset gathering and deployment around periods of global, synchronised dislocations of the type we saw in 2020 will not generate the sort of consistent, uncorrelated returns that allocators seek from alternative asset classes like distressed credit.

Rather, we would propose that it is preferable to allocate to a geographically diversified distressed credit strategy that captures not only the benefits of synchronised global dislocations, but also complement consistency of returns with the attractive opportunities that unfold from recurring, asynchronous dislocations in emerging markets credit.

In short, the party isn’t over. Investors just need to be able to go to where it is taking place.

2020 Recap: The Shortest Distressed Cycle in History?

When credit spreads blew out in March 2020, market observers raised their default rate expectations for the year. Global distressed managers, having had slim pickings since the heyday of the Global Financial Crisis, sharpened their pencils and kickstarted their fundraising machines. Several managers with dry powder in drawdown vehicles, including dedicated dislocation funds established prior to the crisis, were able to take advantage of the brief window of opportunity generated by the selloff. Expectations for a gargantuan cycle ran high amongst the distressed credit community.

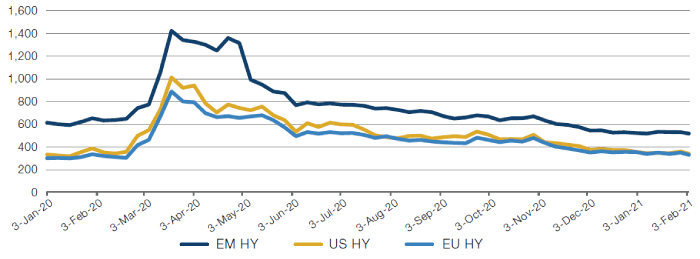

Figure 1. Global Credit Spreads Have Continued to Tighten

Source: Bloomberg; as of 28 February 2021.

But by the end of 2020, unprecedented amounts of stimulus from the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and monetary authorities across the globe had flooded markets with liquidity. Credit spreads fell back towards pre-pandemic levels, and default rate expectations have fallen in tandem. As distressed managers tally their 2020 returns and allocators ponder distressed credit this year, the question is whether the opportunity has passed. Should they await the next global crisis to allocate to the asset class?

A Glance Back at the Last 20 Years – Rarely a Dull Moment for International Distressed

‘Good company, bad balance sheet’ is the truism that is often used to describe an attractive distressed credit opportunity. After all, ‘bad companies’ with flawed business models fall into financial distress all the time, and often make for unattractive investments. In fact, bad balance sheet is not an accurate descriptor – rather it is a mis-priced balance sheet that is a key condition.

So, going back to the basics: a security is deemed to be ‘distressed’ based on its market price and yield spread1, irrespective of the condition of the underlying business, generally because of an unsuitable liability structure in a given market context. Debt securities of ‘good businesses’ don’t usually trade at distressed prices outside major market dislocation, where real-money selling generates the required price action.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, an anecdotal recounting of the distressed credit landscape over the past 20 years shows that the opportunity set of higher-quality businesses with debt trading at distressed prices surged during global financial crises, particularly those crises affecting the two largest high yield markets of the US and Europe in a synchronised fashion. These periods of ‘feast’ for distressed managers can take some time to play out, creating a series of reverberations, second-order effects and delayed reactions, leaving a wake of balance sheet restructurings.

Figure 2. 20 Years of Recurring, Asynchronous, International Distress

Source: Deutsche Bank, S&P, Public Sources; as of 31 December 2020.

During these periods, the larger distressed managers, which are principally focused on the US and to a lesser extent Europe, were able to deploy capital into a higher quality opportunity set. As a result, their returns from these periods of plenty have, on the whole, been satisfactory. But outside of these periods, average returns for many established managers have been lacklustre.2 Our own anecdotal view is that for most of the last decade, a dearth of attractive businesses to invest in in the US and Europe forced US- and Europe-centric managers to deploy into a distressed opportunity set largely comprised of weaker businesses like marginal oil producers or retailers in secular decline. Alternatively, they sometimes opted instead to invest into adjacent strategies like non-performing loans, private credit or other niche or illiquid strategies that require different skillsets, especially when it comes to originating attractive opportunities.

Most interestingly, we find that attractive distressed investing opportunities arise in numbers during periods of asynchronous localised crises in emerging markets (‘EM’). Home to the third largest and rapidly growing USD1.8 trillion high yield Eurobond market, EM crises include examples such as the Asian and Russian crises of the late 1990s and the Latin American crises in the early to mid-2000s. During the 2010s, there were a variety of sizeable and attractive corporate and sovereign situations in Latin American, Ukrainian and Turkish distress, as well as several compelling idiosyncratic credits in Asia. Indeed, in the last decade, it has been possible to buy Argentine essential infrastructure debt at pennies and recovered par. Most importantly, these EM opportunities are often uncorrelated to global equity and credit indices.

Perennial catalysts for these events range from commodity price shocks to balance of payments crises, and they can cause otherwise resilient, systemically important businesses to require debt restructuring. Technical price action caused by real-money selling and the relative absence of dedicated emerging market distressed funds can lead to attractive entry points. Importantly, they also often result in debt-for-debt restructurings that provide liquidity and enable distressed managers to return capital to their clients in timely fashion.

What Now? The Opportunities of Geographic Flexibility

The dawn of 2020 started with pre-existing vulnerabilities in a number of markets. The coronavirus pandemic accelerated the growth trend in tradeable debt stocks, further weakening corporate balance sheets, or temporarily shifting corporate and consumer risk onto sovereign balance sheets. Since then, several weaker sovereigns have defaulted, and EM sovereign default rate expectations remain elevated (Figure 3). As we start 2021, we find that the vulnerabilities of early 2020 have been exacerbated and there is still great uncertainty around vaccination rollouts, virus mutations, the future taxation implications of swollen sovereign balance sheets and gaping fiscal deficits, and first and second-order effects on businesses and consumers. Nobody knows exactly how this will play out or when the next global dislocation might come: the unprecedented growth in tradeable debt stocks combined with heightened uncertainty and vulnerability can be harbingers of attractive prospects for distressed managers.

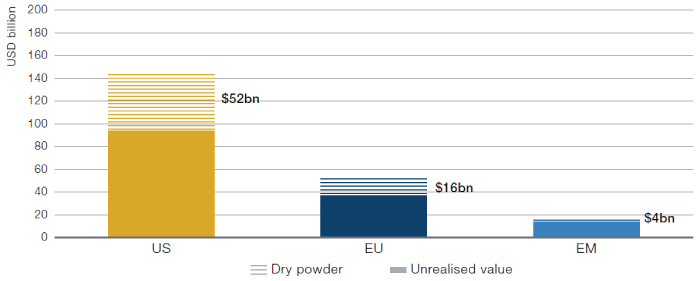

But there is no need to wait. Although we currently see limited opportunity and an excess of distressed capital in the US and Europe, there is ample opportunity and scant competition in emerging markets distressed debt (Figures 4-5). In Latin America, the Argentine sovereign, sub-sovereign and corporate Eurobond stock of approximately USD100 billion is trading at distressed levels. Similar opportunities lie within another USD100+ billion of Andean and Central American Eurobonds. Bellwether debt stocks of over USD500 billion lie within the fragile economies of Mexico, Brazil, South Africa and Turkey. And a number of smaller or frontier Eurobond debt stocks like Zambia or Lebanon also present interesting distressed situations.

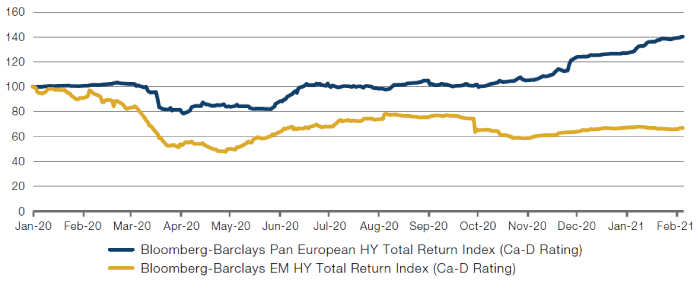

Figure 3. Lowest-Rated EM Bonds Have Not Rebounded as Much as Their European Counterparts

Source: Bloomberg; as of 5 February 2021. Normalised to 100 as of 1 January 2020.

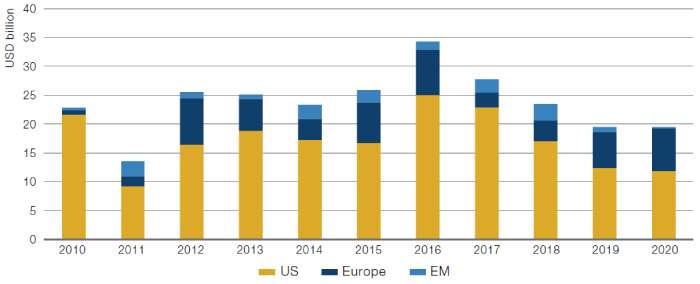

Figure 4. The USD260 Billion Raised for Distressed Credit Since 2010 Mostly Destined for US…

Source: Preqin; as of 31 December 2020.

Figure 5. …Makes Opportunity Set Less Crowded ex-US, Especially in RoW

Source: Preqin; as of 30 June 2020.

Conclusion

Attempting to time allocations to distressed credit around synchronised global dislocations like the one we saw in 2020 can be a fool’s errand. Outside of ad hoc dislocation funds, we believe timing a fundraise for distressed credit around these global crises is impractical given logistical and other constraints, and because these events are infrequent and by their nature difficult to predict or to know how long they last. Importantly, the portfolio diversification value of dislocation funds can be limited, as they tend to express bets correlated to global high yield and equity markets.

The good news is that for those with geographic flexibility to act, the party isn’t necessarily over – distressed credit opportunities still exist. Distressed funds, in contrast to dislocation funds, can benefit from global or localised dislocations, but their uncorrelated alpha depends on the manager’s ability to profitably deploy capital – and, importantly, return capital – through the cycle. As allocators begin 2021 pondering their allocations to distressed credit, we believe they should consider the lessons we take away from the historical landscape of the asset class: avoid trying to time the market and allocate to experienced managers with flexible geographic mandates that can seek out attractive opportunities where they arise.

1. A generally accepted guideline is that bonds trading with a yield in excess of 1,000 basis points over the relevant risk-free rate of return (such as US Treasuries) are commonly thought of as being “distressed.” Distressed bank loans typically trade below USD80.

2. See Edward I. Altman and Robert Benhenni, The Anatomy of Distressed Debt Markets, Annual Review of Financial Economics, December 2019 and CAIA Association Alternative Investments Level 1 Study Material (2015).

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.