The following is an extract from a forthcoming paper on the use of data when investing in emerging markets. If you would like to receive a copy of the full paper when it is published in the coming weeks, please email editor@man.com

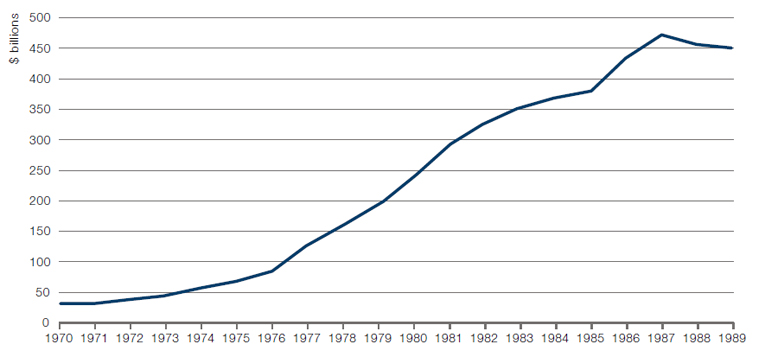

It happened on a Friday the 13th, of course. As Hemingway described bankruptcy, the crisis had happened gradually and then suddenly. After a long accumulation of debt and a spike in interest rates (Figures 1 and 2), several Latin American economies were on the brink. Mexico was the first to fall.

Figure 1: Total Latin American Debt Outstanding, 1970-1989

Source: World Bank, World Bank Debt Tables 1990-91 edition.

Figure 2: Real Interest Rate of Latin American Borrowers and US Real Interest Rate, 1962-1985

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Manuel Pastor, “Latin America, the Debt Crisis, and the International Monetary Fund”. Latin American Perspectives 16, no. 1 (1989). Based on IMF data (1987). The real interest rate from the perspective of Latin American borrowers is calculated by Pastor as the US prime interest rate minus the rate of change of the Western Hemisphere export price index (i.e. the inflation in export prices, calculated logarithmically); the US real interest rate is calculated as the US prime rate minus the US CPI inflation rate.

Having been informed on Wednesday 11 August that the country could not meet principal payments due on the Monday, and that the lending banks would not roll the debt over, Mexico’s finance minister Jesús Silva Herzog set about a drastic series of actions. On the 12th, he closed the exchange markets and permitted banks to buy US dollars for a fixed rate of 69.5 pesos each (below the market rate of around 75 at the time), with deposits denominated in dollars only redeemable in pesos at the fixed rate. The next day, Friday the 13th, Herzog flew to Washington DC to begin relief negotiations with the US administration and IMF.

It was a swift fall from grace for a country that had been enjoying strong growth thanks to high oil prices and easy foreign credit. By late 1982, Mexico faced “zero growth, an inflation rate of 100%, a deficit on current account close to $6 billion, almost no foreign exchange reserves, a public-sector deficit equal to almost 17% of GDP, a breakdown of foreign financial relations and, most important, a general climate of distrust and uncertainty at home and abroad,” Herzog noted. “It is very hard to convince a nation that its boom is over.”

Over the ensuing years, Mexico was one of 16 Latin American countries – and 11 other emerging markets – to restructure their debts during this period.

The 1982 Mexican crisis was the one that alerted the IMF and the world to the possibility of a systemic collapse.

“Although Mexico was not the first indebted economy to erupt, nor the largest, nor the one with the most serious economic or financial problems, the 1982 Mexican crisis was the one that alerted the IMF and the world to the possibility of a systemic collapse: a crisis that could spread to many other countries and threaten the stability of the international financial system,” argued IMF historian and economics professor James Boughton. “Moreover, the Fund’s response to Mexico in 1982 introduced important innovations in the speed of negotiations, the role of structural elements in the policy adjustment program, the assembling of official financing packages, and – most important – relations between the Fund and private sector creditors.”

Just the Facts

One seemingly minor consequence was the start of work by the IMF and World Bank on “standards and codes”, part of which standardises countries’ reporting of their finances and economic statistics. Today, almost every state is aligned to one of the reporting standards (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3: IMF Reporting Standards Across Developing Economies

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: IMF (https://dsbb.imf.org/); as of October 2022. e-GDDS = Enhanced General Data Dissemination System. SDDS = Special Data Dissemination Standard.

Figure 4: History of the IMF’s Data Standards Initiatives

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: IMF (https://dsbb.imf.org/); as of October 2022.

Yet while there were clear benefits to the homogenisation of data about emerging economies, it did to an extent diminish the value of data to individual investors in their sovereign debt. There is little to no value in mere access to information that is easily available to every other market participant. Equally, though, the same could be said of stocks – if all public companies must report their earnings and balance sheets according to common accounting principles, is it possible to have an informational edge?

A Question of Interpretation

The true edge lies not in the information itself, but its analysis and interpretation.

That, however, is the wrong question. The true edge lies not in the information itself, but its analysis and interpretation. Data alone are not a panacea. “It doesn’t show on any maps, but there’s a new mountain on the planet – a towering $500 billion of debt run up by the developing countries, nearly all of it within a decade,” warned The Wall Street Journal in January 1981. “To some analysts the situation looks starkly ominous, threatening a chain reaction of country defaults, bank failures and general depression matching that of the 1930s.” Prescient – but ignored by many investors over the subsequent 18 months until the emergence of the crisis. Data must be understood, and acted upon, correctly.

Investors in emerging-market bonds today have two broad sources of data at their disposal: macroeconomic and market. These encompass vast swathes of traditional information, but in the latter category it is also increasingly possible to extrapolate sentiment and aggregate positioning in a meaningful way – crucial in a risk asset class.

For example, there are now enough dedicated emerging-market debt funds – and generalist fixed-income strategies with exposure to these areas – to regress their daily returns against asset performance and determine allocation trends. Understanding how others are positioned is as critical as understanding fundamentals, in our view. With the liquidity provided by sell-side broker-dealers having significantly decreased since the 2008 crisis, at the same time as fund (particularly ETF) exposure to emerging-market bonds has significantly increased, this mismatch has led to sharp selloffs as passive sellers find few market-making buyers. Monitoring changes in fundamentals alone is unlikely to give advance notice of these shifts, but watching for crowding may provide early warning on the direction of flows.

Macro Refresh

While the raw numbers are now commoditised, what is often lost is the context.

Macroeconomic fundamentals cannot be discarded entirely, though. While the raw numbers are now commoditised, what is often lost is the context; economic datapoints do not exist in isolation and must be considered within the prevailing regime. This includes global macroeconomic, market, and country-specific regimes – and their interaction. These dynamics make it impossible to draw substantive investment implications from a purely macroeconomic model.

A country with a fully floating currency, for instance, will behave differently from one with a pegged currency even if their macroeconomic situation appears similar. Both may have large and nominally comparable export sectors, but they will be subject to different forces. The macro variables for a fiat issuer typically look better than those of states with floating regimes – up until the moment authorities in the former group have to devalue their currency.

A further challenge is that through much of the period for which comprehensive data on emerging economies are available, quantitative easing has distorted trends, patterns and performance. With sufficient years of data, it’s likely that advanced quantitative analysis could lead to the development of a robust investment programme for emerging-market debt. The present dataset, however, is so skewed by monetary policies which are already reversing that the past is an even less reliable guide to the future than usual.

Higher-frequency data have limited utility in emerging-market sovereign bonds too. Given investors’ primary focus in this area is the ability of countries to pay back their debt, changes large enough to influence this likelihood tend not to be so subtle that they only manifest in micro data. These types of alternative data could be more useful in emerging corporate bonds, but the potential payoff from novel insights is constrained by liquidity in this space. Trading volumes are highly concentrated in the very largest corporate issuers, such that even if an attractive opportunity is identified it is difficult to gain meaningful exposure from a portfolio perspective (and, conversely, hard to exit in a negative credit event). A similar principle applies on the government side: 18 countries represent around 80% of the benchmark1; standardised data are available for each, so it is hard to find an edge from the numbers alone.

The Price is Right?

Looking further into the future, the available data on emerging-market bonds are likely to proliferate to match those for developed economies. Yet even as that occurs, the a fore mentioned challenges remain. Consider the possibility of some alternative data becoming a leading indicator of an important economic release. The question is then how the market will respond to that release, not least given central banks’ reaction function. These decisions rest on analysis and interpretation of what is already priced.

The role of data in emerging-market debt, then, is in grounding subjective decision-making in objective observations. Investment teams can interrogate both consensus and non-consensus expectations that deviate from a data-led base case, exploring valuations and positioning in this light. Using quantitative evidence to test qualitative judgement in this manner can reduce the room for error in decision-making.

Special FX

An illustration can be found in currency markets. Traditionally, investors in emerging-market bonds have looked to a country’s current account in absolute terms for a guide to its currency’s trajectory. But by the time a current account turns emphatically from positive to negative, or vice versa, it is typically too late to benefit from initiating a currency position.

Regressing many years of trade balances and currency returns with certain seasonal adjustments, on the other hand, highlights a correlation between outperformance and improvements in the current account over a specific near-term period relative to a specific medium-term period. The qualitative intuition was that sequential improvements could send an informational signal, even if the absolute situation still appeared deeply unattractive. Vast data processing tested this thesis, to arrive at the most instructive application of the theory.

Similarly, automated monitoring of the Taylor rule – a rules-based metric that indicates where interest rates should be, given inputs such as inflation and GDP – can draw investor attention to areas where rates seem anomalous. It’s not sufficient to trigger automatic trades, but it can point to risks and opportunities for further analysis that may be missed without the data-instigated alerts.

The data alone should not set investment decisions in motion, but can impose a measure of objectivity on portfolio choices.

Combine that rate assessment with the pricing of the local currency, and it’s possible to question whether the relevant central bank is behind or ahead of the curve in a way that is based on data rather than subjective policy views. The data alone should not set investment decisions in motion, but can impose a measure of objectivity on portfolio choices.

History Rhymes

Fuelled by cheap debt, global economies and markets had been rallying. The end came with high inflation and tighter monetary policy in the US and Europe. Plenty of investors today can hear the echoes from the late 1970s and early 1980s.

“Financial markets at least occasionally – and sometimes spectacularly – initially misjudge and eventually aggravate bad news,” observed Boughton, the IMF historian, in 1997. “In the 20th century, when economic activity was affected gradually by financial disruptions, allowing financial markets time to correct their own course was often feasible. In the 21st century, that luxury will no longer be affordable.”

Data can certainly give emerging-market debt investors a baseline for analysing events and markets but, without appropriate interpretation, such raw information indeed risks being misjudged and aggravating decision-making. Allocators cannot afford to luxuriate in fast data.

Herzog’s time as Mexico’s finance minister came to an end in 1986 for, according to a local official, being “a defender of the IMF without considering the internal repercussions”. In 1989, he was asked whether the Mexican government had instructed his department to conceal a relaxation of the fiscal reins to keep international capital flowing to the country.

“Yes, it had, but in today’s world the chances of doing that are limited,” Herzog explained. “The numbers are public, and reserve figures are known abroad as soon as they are available at home. Moreover, in matters of economics it is increasingly difficult to ignore reality.”

Better data may well have made it harder for investors to ignore reality, but more data can make it easier to misunderstand reality. Data and rigorous analysis by experienced professionals must be inseparable.

--With contribution from Guillermo Osses (Head of Emerging-Market Debt Strategies at Man GLG)

Further Reading

Valuations, Fundamentals and Positioning: How to Spot Red Flags in Emerging-Market Debt. We explain how valuations overlooked ESG factors ahead of the Russian invasion and how a robust framework can help EMD investors spot the risks. https://www.man.com/maninstitute/valuations-positioning-red-flags

How Will US Monetary Policy Impact Emerging-Market Debt? As US inflation rises and the move in energy and food prices creates a meaningful risk of recession, how will the Federal Reserve respond? And what impact will that have on emerging-market debt? https://www.man.com/maninstitute/monetary-policy-emerging-market-debt

References

James Boughton, From Suez to Tequila: The IMF as Crisis Manager. IMF Working Paper No. 97/90 (1997)

James Boughton, Silent Revolution: The International Monetary Fund 1979-1989. IMF (2001)

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future. Vol. 1, An Examination of the Banking Crises of the 1980s and Early 1990s (1997)

Manuel Pastor, “Latin America, the Debt Crisis, and the International Monetary Fund”. Latin American Perspectives 16, no. 1 (1989)

Jesús Silva Herzog and Blanca Heredia, “Interview: Jesús Silva Herzog”. Journal of International Affairs, vol. 43, no. 2 (1990)

Jocelyn Sims (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago) and Jessie Romero (Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond), Latin American Debt Crisis of the 1980s (2013)

1. Source: J.P. Morgan; as of October 2022.

You are now leaving Man Group’s website

You are leaving Man Group’s website and entering a third-party website that is not controlled, maintained, or monitored by Man Group. Man Group is not responsible for the content or availability of the third-party website. By leaving Man Group’s website, you will be subject to the third-party website’s terms, policies and/or notices, including those related to privacy and security, as applicable.