Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. The Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative needs work but is still a positive step for the industry.

Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. The Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative needs work but is still a positive step for the industry.

November 2021

In our view, net zero represents a critical evolution in how we, as asset managers, practise responsible investment, taking the environmental demands that we make of the companies we own and applying them – for the first time – to ourselves.

Introduction

Responsible investing has been one of the fastest growing and most welcome trends within asset management during the last decade. As with any emerging trend, as more investors begin to engage, levels of sophistication begin to increase. Just as systematic strategies have become far more complex than during their genesis in the 1980s, responsible investing has also transformed. What began as a few investors applying exclusion lists to certain sectors has now become a fully fledged discipline of asset management in its own right, with applications for all types of strategy.

It is this spirit of evolution and increasing sophistication that brings us to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative (‘NZAMI’), a movement which mobilises asset managers to use their portfolios to support the goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. In our view, net zero represents a critical evolution in how we, as asset managers, practise responsible investment, taking the environmental demands that we make of the companies we own and applying them – for the first time – to ourselves.

In this article, we outline what net zero is likely to entail, how current best practice is heavily focused on long-only strategies and the current challenges with the initiative for alternative managers. But most of all, it will stress what Man Group passionately believes: that the climate emergency is one of the greatest crises facing humanity, and that net zero is an evolution in how responsible investing will enable asset managers to do their part in solving it.

What Is the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative?

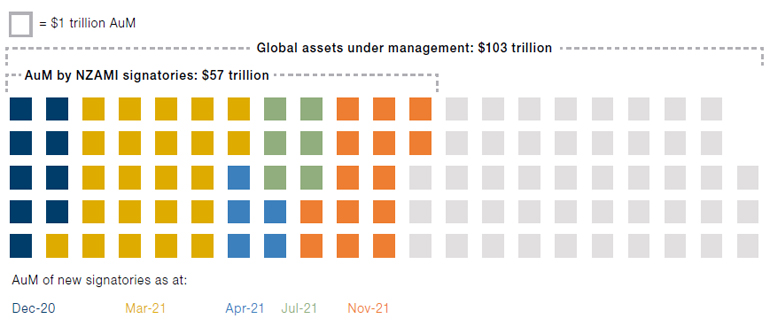

Launched in December 2020, the NZAMI is a network of asset managers which aims to encourage the industry to work towards a goal of net zero emissions. About 220 signatories controlling USD57 trillion in assets have signed up to NZAMI, representing more than 55% of global AuM.

Figure 1. Assets Under Management by NZAMI Signatories Now Represents Over 55% of All Managed Assets

Source: Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative; as of 1 November 2021, global assets under management data from BCG; as of 31 December 2020.

By registering for the NZAMI, assets managers take on three main commitments:

- Work in partnership with clients on decarbonisation goals, consistent with an ambition to reach net zero emissions by 2050 or sooner across all assets under management;

- Set an interim target for the proportion of assets to be managed in line with the attainment of net zero emissions by 2050 or sooner. The target should be no later than 2030;

- Review the interim target at least every five years, with a view to ratcheting up the proportion of AUM covered until 100% of assets are included.

While the commitments themselves are fairly straightforward, achieving them requires significant effort and is roughly divided into two buckets:

- For those assets managed in line with the commitment, signatories’ interim targets must take account of Scope 1 and 2 emissions across portfolios, and material Scope 3 emissions as far as practicable. New investment products should be designed so that they not only increase investment in climate solutions, but also align with the goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. When these portfolios are unable to entirely eliminate emissions, carbon offsetting should be used – where carbon reducing activities are paid for in direct proportion to the emissions created. Signatories should also annually publish Task Force on ClimateRelated Financial Disclosures (‘TCFD’), including a climate action plan, and submit these to the Investor Agenda for review.

- For those assets not managed in line with a net zero target, asset managers would have to implement a stewardship and engagement strategy, consistent with the net zero target. This approach also extends to data and analytics, with signatories to provide clients with information on net zero investing and climate risk. They should also engage with other non-investment institutions (such as credit ratings agencies, stock exchanges, data providers, investment consultants and proxy advisers) to make sure products and services are in line with the net zero target.

In our view, best practice would be to set a series of short- and longterm targets for which assets will be managed under a Net Zero approach, and repeatedly re-assess progress to allow for continual improvement throughout the next decade.

Best Practice: Challenges and Opportunities

For asset-management firms aspiring towards Net Zero, the broad framework provides a number of potential opportunities, as well as challenges of varying difficulty, to contend with. These differ widely for various funds, with divergent demands for long-only asset managers versus their alternative counterparts.

Let’s start with long-only managers.

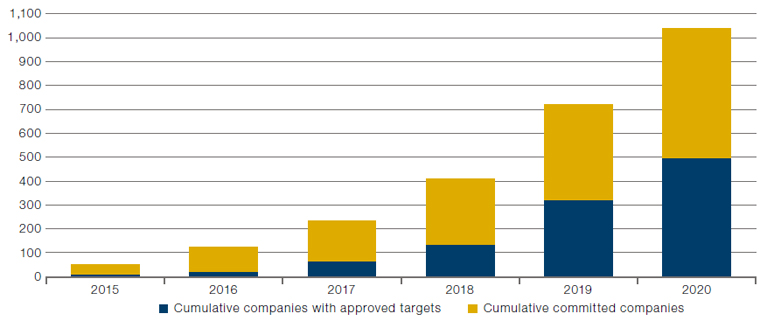

Long-only managers of corporate securities have, in a sense, the easier role. In our view, best practice would be to set a series of short- and long-term targets for which assets will be managed under a Net Zero approach, and repeatedly re-assess progress to allow for continual improvement throughout the next decade. This makes the change easier to implement, as it doesn’t happen all at once. When a time horizon has been identified for targets, focus moves to implementation. The first step is to select those assets for which net-zero alignment is easiest. According to the Net Zero Investment Framework, these would typically be long-only strategies in listed equities and corporate fixed income, reflecting that corporate activities offer the greatest scope for reducing emissions, and are thus the most important to the transition to net zero. Securities could then be assessed on their net zero credentials and trajectory, using frameworks developed by the Science Based Targets initiative (‘SBTi’) or the Transition Pathway Initiative (‘TPI’), to calculate the overall emission status of portfolio assets.

Figure 2. Total Number of Companies Committed to SBTi and Total Number of Companies That Have Set Targets

Source: SBTi; Between 28 May 2015 and 31 October 2020.

Within the long-only space, there is still a certain amount of complexity. Let’s take offsetting as an example. Offsetting is a method by which companies can compensate for their carbon emissions. This takes two forms: commissioning carbon removing projects such as tree planting, which actively reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, or by paying for carbon avoidance measures. The two are not equally efficacious, with avoidance offsets raising some concerns. While paying someone not to cut down trees would count as an emissions avoidance offset, it doesn’t provide positive progress towards reducing carbon emissions – it simply prevents further deterioration.

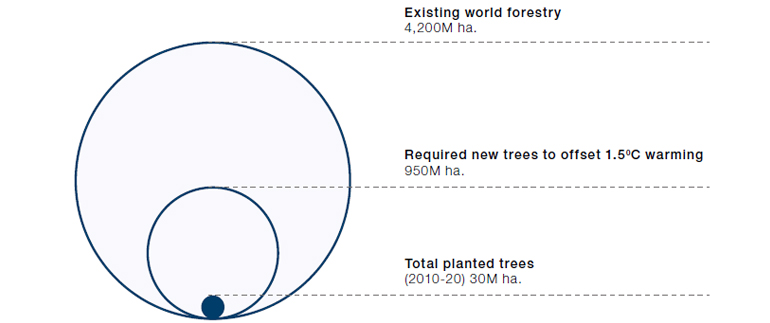

The potential for nature-based carbon offsetting solutions is constrained by both space and time.

However, current forms of carbon removal are not going to be enough. The potential for nature-based carbon offsetting solutions is constrained by both space (there is not enough land for the requisite hectares of trees) and time (trees can take up to 30 years to reach their maximum carbon sequestration levels). Figure 3 shows that to offset the existing 1.5 degrees of global warming, we would need to plant 950 million hectares of new trees. For context, Canada’s landmass is 998.5 million hectares.

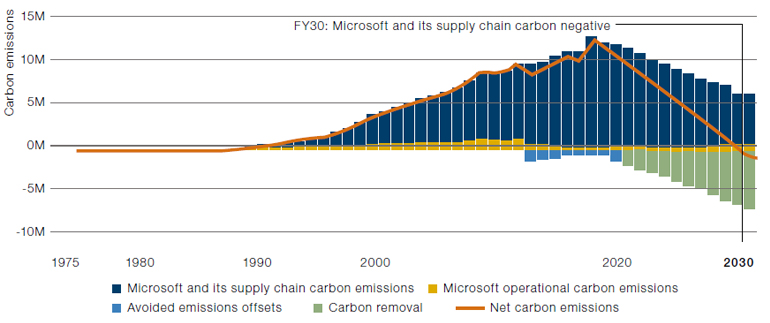

Fortunately, companies are beginning to recognise the urgent need to transform how offsetting is practiced. For instance, Microsoft has achieved carbon neutrality primarily through investing in avoidance offsets. However, the company has committed to shift its focus away from avoidance and towards carbon removal, via afforestation and reforestation, but also soil carbon sequestration, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage and direct air capture. In addition, it will overhaul its procurement processes to levy an internal tax on Scope 3 emissions and will also deploy its balance sheet to invest in carbon removal technology through its USD1 billion Climate Innovation fund (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The Problem With Planting Trees to Offset Emissions

Source: Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Man Group; as of 20 October 2021.

Figure 4. Microsoft’s Pathway to Negative Emissions by 2030

Source: Microsoft; as of 20 October 2021.

Note: The organisations and/or financial instruments mentioned are for reference purposes only. The content of this material should not be construed as a recommendation for their purchase or sale.

From an asset management perspective, there is also recognition that offsetting throws up problems. The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (‘IIGCC’) argues that carbon offsets should not be used at the portfolio level. However, if no other technologically or financially viable alternatives are available to reduce emissions, they do allow for offsets to be used. However, these must be investments in long-term carbon removals, thus disqualifying the use of avoided emissions.

If we are to minimise or avoid the use of offsets at the portfolio level, then long-only managers are likely to be forced into sectoral and factor biases which they might not ordinarily take. Certain sectors will find it much easier to reduce or eliminate their emissions entirely: tech companies or banks will find it far easier to eliminate their emissions than miners or construction firms, as their products and services are nonphysical. Without offsetting and without shorting, long-only managers are likely to be crowded into sectors which have intangible rather than fixed assets, and provide services rather than goods.

This would likely be tantamount to implementing an exclusion list, something which many responsible investors have moved away from. The solution provided by the Net Zero initiative is therefore stewardship; where offsets may be unavoidable for certain industries, managers need to engage with companies to ensure they are setting credible emissions reduction targets and using high quality offsets. Until we achieve Net Zero at a corporate level, it will remain difficult to achieve at a portfolio level without offsetting – which puts the onus onto asset managers to drive progress.

By many accounts, policy signals appear to already point to larger, higher quality offset markets. In a recent episode of Man Group’s ‘A Sustainable Future’ Podcast, CFTC Acting Chairman Rostin Behnam discusses by virtue of carbon being a commodity, the CFTC’s interest in helping to develop and regulate offset markets to support net zero objectives. Indeed, Barclays Research forecasts the growth of voluntary carbon markets to reach USD250 billion per annum by 2030 and as much as USD1 trillion per annum by 2050 relative to USD500 million currently.

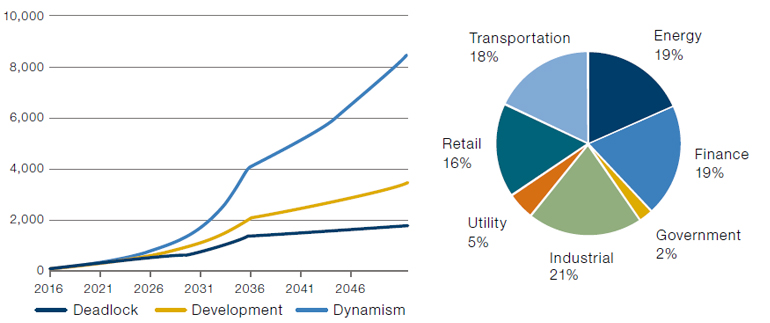

Figure 5. Issued Carbon Credit Scenarios Versus Users of Carbon Credits by Industry

Source: Barclays Research; as of 18 October 2021.

Without offsetting and without shorting, long-only managers are likely to be crowded into sectors which have intangible rather than fixed assets, and provide services rather than goods.

As soon as we move away from long-only and towards alternatives, things become even trickier.

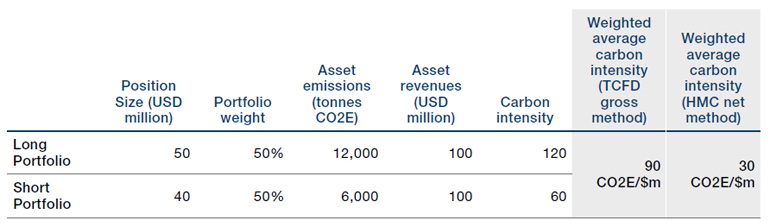

Exactly how portfolios can account for shorts within a net zero framework is contested. If we count short positions as negative, this would reduce net carbon exposures in portfolios. However, given that shorting does not have a direct effect on carbon emissions (although it has an indirect effect by raising the cost of capital for the emitter), should it be included? The IIGCC gives limited guidance on how shorting should be treated, whereas the TCFD recommends the gross values be used i.e., that shorts should add the total value of the carbon emissions of their short book to their long book, without differentiating between the two. The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (‘SFDR’) likewise ignores shorts, introducing a framework to describe carbon exposures on a gross basis. In contrast, the Harvard Management Company (‘HMC’) suggests using ‘negative emissions accounting’, which would allow short sellers to deduct the carbon emissions of their short positions from their gross total; in the eyes of Harvard, a short is making it more difficult to emit by raising the cost of capital, and therefore should be credited with negative emissions. That there is no consensus on how to treat shorts makes life especially difficult for an alternative manager. Indeed, it is possible to foresee a scenario where managers are reluctant to short high-emitters if the TCFD preference becomes widespread – which would clearly be a self-defeating outcome from an emissions perspective.

Treating shorts as notional offsets is equally problematic. Similar to avoidance offsets at a company level, it does nothing to remove carbon at the portfolio level.

However, treating shorts as notional offsets is equally problematic. Similar to avoidance offsets at a company level, it does nothing to remove carbon at the portfolio level. In our view, the best solution would be to describe portfolio carbon exposures on a gross long basis, with the net figure produce by negative emission accounting offered only as supplementary information. By including a net figure, portfolio managers can demonstrate that they are indeed running short exposures to carbon stocks and emphasise to clients that they are not greenwashing. However, by using gross figures, the incentive to actively reduce carbon exposure and to pressure companies to reduce emissions is maintained – the ultimate aim of the Net Zero Initiative.

Figure 6. Different Methods for Accounting for Short Positions

Source: Man Group.

Note – this schematic is an example for illustrative purposes only.

Likewise, if we move away from corporate securities, there is no agreed method for calculating the carbon emissions that should be allocated to a sovereign bond. This is ultimately a data issue, with a lack of forward-looking emissions and alignment data available for sovereign issuers – inhibiting asset managers’ ability to conduct the more sophisticated alignment analysis that can be done for corporates. With limited data, even if investors pursued an exclusion approach, eschewing the debt of highly polluting economies, this presents something of an ethical conundrum. Often the highest emitters are emerging economies, which rely on overseas investment to grow their economies and lift their citizens out of poverty. There is no easy answer. The IIGCC advocates assigning to sovereign issuance all the emissions associated with a territory after normalising for GDP per capita, while increasing allocations to green or climate bonds. However, it still recommends divestment from repeated poor performers, which again raises the prospect of denying capital to the developing world.

Derivatives are another equally complicated area. Many strategies, especially systematic strategies such as CTAs, make heavy use of derivatives like futures instead of looking to hold the underlying securities. In many cases, this is due to the greater liquidity or cash efficiency offered by derivatives for those strategies which trade frequently. Interest rate swaps, commodity futures and currency strategies also complicate matters. Consider a mining company which produces thermal coal or an oil major. Who should be considered the owner of the emissions – a long-term owner of the underlying equity, a CTA which briefly traded a basket of oil equity futures, or a fund which is long the oil or coal itself? Not only do derivatives raise the prospect of double-counting emissions, but the often-short term nature of their holding period also makes accurately reporting a portfolio’s Net Zero status a challenge. If a Momentumbased strategy is both long and short oil futures within a year, how should it report and be treated, given that it is effectively indifferent to the characteristics of the underlying security? If asset managers don’t own the underlying asset, they have a very different relationship with a company than, say, a common stockholder.

Derivative strategies traditionally take a more limited approach to engagement, diluting – though not eliminating – the ability of asset managers to engage in stewardship. This is problematic from a Net Zero perspective. For those assets which are not managed in line with a Net Zero target, firms are required to implement a stewardship and engagement strategy. There is currently a lack of guidance on this topic; the IIGCC, for instance, makes no mention of derivatives or futures in its Implementation Guide. This is itself reflective of the fact that much of the impetus and organisation of the Net Zero campaign comes from not-for-profits rather than asset managers themselves. If we are to see comprehensive guidance, investors and asset managers will need to take more of a lead.

For the Net Zero Initiative to be forward looking, it also needs to take account of new developments within asset management. Whether or not one thinks that cryptocurrencies are the future, more and more asset managers are trading them as part of their strategies. The IIGCC offers little guidance on how cryptocurrencies should be treated from a Net Zero perspective. Given their huge energy consumption and limited value (save as a vehicle for speculation), it is difficult to foresee how cryptocurrencies can be made to fit a Net Zero framework. Nevertheless, as it becomes more widely traded, asset managers will have to square the circle, and come up with an industry-wide framework for its treatment.

The initiative is imperfect, but provides a forum for asset managers to refine their practices and improve. Ultimately, perfect should not be the enemy of good: we believe the Net Zero initiative is a vastly positive step for the industry.

Conclusion

While providing a number of potential opportunities, the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative also comes with challenges of varying difficulty, especially as it pertains to alternative asset managers. Until these challenges are resolved, we will fail to include huge swathes of the modern asset management industry and undermine the effectiveness of the entire Initiative.

While the situation is far from perfect, it is worth stressing that this is an evolutionary process. Working groups are currently in existence to improve guidance on contested issues. In the short term, the direction of travel should be clear. Asset managers need to set clearly defined targets for the amount of assets they will manage under a net zero strategy, and commit to transforming their portfolios.

Just as ESG data has undergone a revolution, we expect that asset managers who are committed to net zero will continually refine their practices, developing consensus over time and improving their methodologies. While we don’t have the answers now, the momentum the initiative is generating makes it inevitable that more clarity will emerge. The initiative is imperfect, but provides a forum for asset managers to refine their practices and improve. Ultimately, perfect should not be the enemy of good: we believe the Net Zero initiative is a vastly positive step for the industry.

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.