When it comes to the Covid-19 vaccine, it pays not to profit from disaster.

When it comes to the Covid-19 vaccine, it pays not to profit from disaster.

January 2021

This article was originally published in the Financial Times on 23 December, 2020.

Introduction

The markets seem to have decided that Pfizer and Moderna are the winners of the Covid-19 vaccine race. While the 90% plus effectiveness reads of their vaccine trials sent shares in both companies soaring, Oxford University/AstraZeneca’s lower effectiveness and more muddled safety release saw more than USD4 billion wiped off the British-Swedish firm’s stock price.

The response was perhaps understandable. After such strong reads from the first two releases (three if we count Russia’s Sputnik V), the disappointing AstraZeneca figures were perhaps bound to prompt downward pressure on the company’s shares. Since then, AstraZeneca’s stock price has staged a slight rally, but there is a clear lack of euphoria surrounding this vaccine compared to its mRNA competitors.

But we may be missing something crucial here: the fact that a Covid-19 vaccine is unlikely to be a huge source of near-term profitability for any firm.

We are not in a world where a company can be seen to be profiteering from the pandemic and even if a coronavirus vaccine becomes as regular as flu jabs, it is unlikely ever to be a high-margin product. Rather, the real winner in the vaccine race will be the business that is able to generate the most positive impact from its efforts and to score the biggest PR win. When the dust settles, that may well be AstraZeneca.

The Case for AstraZeneca

One of the biggest financial stories of 2020 was the inexorable rise of ESG investing. In the UK, investors allocated almost four times as much to ESG-related strategies in the first three quarters of 2020 as they did in the same period last year – GBP7.1 billion versus GBP1.9 billion. This was dwarfed by global allocations: currently more than USD1.2 trillion is managed, according to ESG guidelines.

It’s striking, though, that both of the leading ESG ratings providers – MSCI and Sustainalytics – rate the pharmaceutical industry poorly when it comes to key metrics, and particularly the social impact of their activities. My colleague Mike Canfield noted in a recent article that the pharmaceutical industry appears to have taken a business model that is objectively good – curing the sick and protecting the well – and turned it into something far more equivocal, with allegations of price gouging and putting profits before patients. It may be that the Covid-19 crisis provides an opportunity for big pharma to regain some of the ESG-related ground it has lost in recent years.

The Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine has clearly set itself out as the ESG investor’s provider of choice. While Pfizer/BioNTech has agreed to sell its vaccine at USD19 a dose and Moderna at around USD30, Oxford/ AstraZeneca has stated explicitly that it will sell its vaccine at cost price until at least June next year, or as long as pandemic conditions persist, a cost that equates to around USD4 a dose.

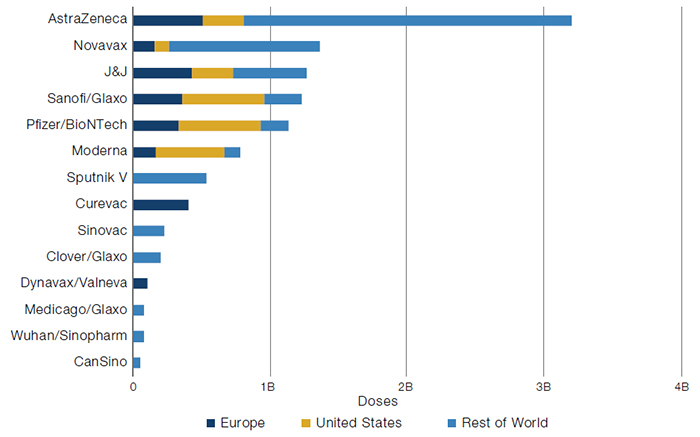

What’s more, there is a clear divide between the mRNA vaccines and Oxford/AstraZeneca in terms of distribution. Oxford/AstraZeneca has made it clear from the start that its vaccine is intended to be globally available and affordable for low-income countries. Figure 1 gives an indication of the likely distribution of each vaccine and illustrates the clear divide between the mRNA platforms and Oxford/AstraZeneca.

Figure 1. The World Looks to AstraZeneca

Source: Airfinity.

About 64% of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines will go to low income countries. For Pfizer/BioNTech, the figure is just 4%, while Moderna will only distribute its vaccine to wealthy nations.

Partly this is to do with logistics – the mRNA vaccines require super-cool storage (Pfizer/BioNTech’s at -70 degrees), while the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine can be stored for extensive periods in normal refrigerators. The numbers also play in AstraZeneca’s favour – they have just increased production to 3 billion doses, which, particularly if they end up using the seemingly more effective lower dosage model, suggests that there is the potential for the vaccine to be the dominant model for addressing a decent proportion of the world’s population. It’s noteworthy that Oxford/AstraZeneca have been working closely with a host of supra-national agencies, including Gavi and the Serum Institute of India, to coordinate vaccine delivery to low-income nations. At every step, the Oxford/AstraZeneca team appear to be led by the clear long-term reputational and ESG-related benefits that will accrue to those who see Covid-19 not as an opportunity for profit but as a means of restoring faith in a much-maligned industry.

Profiting From Not Profiting From Crisis

It was telling that the first major step Donald Trump took post-election was to initiate his drug price reforms. Big pharma is almost unique in attracting the ire of both sides of the political spectrum; Trump seems to want to make sure that he gets the credit for tackling an issue which he can be certain his successor will address if he does not. The industry faces a PR crisis; Covid-19 and big pharma’s pioneering role in providing a solution to the pandemic may be a counterbalance to these reputational issues. But while Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have gestured toward equitable distribution and affordability, Oxford/AstraZeneca seems like it is seizing the opportunity with both hands.

A recent report by the People’s Vaccine Alliance (‘PVA’) observed that, as of 8 December, countries with 14% of the world’s population have secured 53% of the most promising vaccines. The PVA identified 67 low-income countries where they expect nine out of 10 people not to receive the vaccine in 2021. Of these countries, five – Kenya, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan and Ukraine – have reported a combined caseload of more than 1.5 million people.

Governments and the pharmaceutical industry alike should be focused on the troubling discrepancy between wealthy nations, who have stockpiled sufficient vaccines to inoculate their populations three times over, and poorer countries whose governments are stretched to secure doses for health-care workers and the most vulnerable.

Conclusion

There’s a reason beyond ethics that ESG has gained such a following in recent years. You don’t have to be Thomas Piketty to recognise that inequality poses a significant risk to the global system as it stands. Far-sighted investors recognise that firms need to play a part in redressing the most egregious imbalances, whether these be social or environmental. So while the mRNA vaccine producers may have had a brief spell in the sun following their stellar efficacy reads, I still think that AstraZeneca may be the long-term winner of the vaccine race.

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.