Geopolitical conflicts have expanded beyond traditional warfare and now involve weaponising commodities. Also, the Bank of Japan needs to perform a careful policy balancing act over the weak yen.

Geopolitical conflicts have expanded beyond traditional warfare and now involve weaponising commodities. Also, the Bank of Japan needs to perform a careful policy balancing act over the weak yen.

May 7 2024

The global world order is seeing a gradual atrophy of Pax Americana and a shift towards a paradigm defined by increased geopolitical fragmentation and the formation of multi-polar spheres of influence.

Conflicts in this new paradigm have expanded beyond traditional warfare of bullets and tanks towards wider dimensions of battlefield.

The new theater of conflicts is now defined by trade wars, financial and currency sanctions, cybersecurity threats, technology exclusions, supply chains and increasingly a trend to weaponise commodities.

The world of natural resource supply and demand is marked by production that is overly concentrated in certain regions with consumers reliant on a free flow of trade and imports. Unlike a factory or semiconductor lab, a farm or mine cannot be relocated to friendlier shores. As such, natural resource disruptions are very sharp, volatile, and complex. Demand in the short-to-mid run is fairly inelastic with substitutions difficult in the short term.

Natural resource supply chains are also complex systems with midstream processing capacity and transportation often as critical as upstream production. Recent market headlines have centered on developments in the oil and natural gas markets but it is equally important to understand the geopolitical ramifications in metals, materials, food, agriculture and renewable energy.

In many ways, the Russia/Ukraine conflict was the opening salvo for the weaponisation of commodities. As Russia withdrew natural gas supplies (Figure 1), European natural gas prices (as measured by TTF) spiked over 300% from the start of the conflict.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Natural gas, a commodity that was not at the forefront of investors’ minds, was suddenly thrust into global prominence, highlighting how important it was to the global economy and how reliant Europe was on one producer. Similarly, crude oil has been one of the best performing assets thus far in 2024 due to the increasing geopolitical tensions in the Middle East.

Uncertainty in the region has sparked fears of supply disruptions as the Middle East produces roughly a third of global oil demand and certain logistical choke points like the Strait of Hormuz in which approximately 20% of the global oil consumption transits through.

Potential future conflicts and investments opportunities can be found in a wide range of areas such as refined oil products (global capacities additions have been concentrated in the ME and Asia), the disruption of trade routes causing increase in shipping ton-miles or natural gas “BTU parity (British Thermal Unit parity)” driven by the upcoming wave of global LNG capacity.

Risk across metals

Risk is not isolated to energy; geopolitical ramifications can be seen across metals and materials as well. While disorder in the global metal markets may not cause as much broad economic damage as energy, the effects can be wide ranging and extremely disruptive to certain industries.

Trade sanctions can create regional pricing dislocations and potential shortages to supply chains. Like oil, gold has also seen a strong price performance in 2024 as central banks stepped up buying of the physical asset since the start of the Russia/Ukraine conflict in a bid to diversify assets and to slowly break the US dollar hegemon. Another area of potential future conflict rest in the global uranium markets. While Russia is not the largest raw uranium producer, it is responsible for over 40% of the global enriched uranium supply. Disruptions in this critical element can have as severe economic effects as natural gas (if not more!).

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Food is most important commodity group

Global food and agriculture is perhaps the most important commodity group (but also the most overlooked) and most rudimentary form of energy – disruptions in this system have more severe ramifications than slower economic growth (humanitarian catastrophes in starvation in certain regions).

The global economy has seen decades of relative food security and stability with food poverty near lows. Yet, is this complacency masking underlying secular shifts? The largest commodity cartel is OPEC which controls approximately a third of global crude supplies – compare this to the global grain trade – where the top 10 producers of wheat, corn and soybean controls over 80% of the export market.

Compounding geopolitical uncertainty with climate change which can drastically alter the beneficial growing and production trends we have experienced in the past century, the potential for increased food, grain and protein price volatility is biased meaningfully higher.

Moving beyond traditional natural resource sectors, the effects of global fragmentation can also be seen in energy transition and its surrounding supply chains. While countries like China are very reliant on natural resource imports, they have moved very quickly to dominate the renewable energy supply chain.

The world simply cannot go green without China. Russia may dominate in natural gas, wheat and uranium but China has staked out a dominance in controlling over 70% of the global solar panel supply chain and over half of the lithium processing market. Looking at the global lithium-ion battery capacity, the top 5 names are all domiciled in Asia with China taking a wide lead.

Japan’s Yen Conundrum

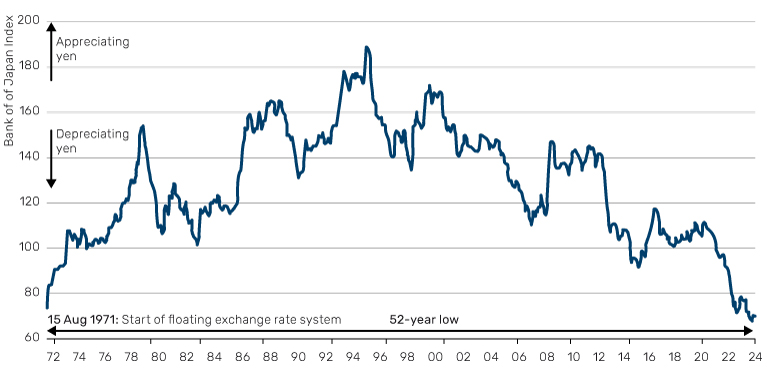

Last week’s sudden strengthening of the yen, suspected to be a currency intervention, has highlighted authorities’ unease with the pace of the slide in the currency this year. On a trade- weighted basis, the yen is now the weakest since the introduction of the floating exchange rate at the end of Bretton Woods (Figure 3).

Any central bank actions now involve a careful balancing act between smoothing short-term volatility, longer term monetary policy tightening and the right rhetoric so as to not spook markets.

The weak yen is now at a level where it’s seen as broadly negative and problematic and the drawbacks are outnumbering any previous perceived advantages for exports. The Tokyo Chamber of Commerce last month complained about the weak yen’s cost impacts for smaller businesses, and for large corporates, the Keidanren business lobby, airlines, and retailers have all been concerned that the weak yen is a drag. The voting public doesn’t like their cost of living increasing on the back of internal and external inflationary forces. Japan as a net energy importer has had to subsidise energy bills, but that has been stepped back recently putting more pressure on households. Also, other countries are worried about it being anti-competitive.

Figure 3: The Real Effective Exchange Rate is now at the lowest in 52 years

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

These are long term considerations that interventions won’t fix. Any interventions are and will only be short lived and meant to deal with volatility. They can’t fight a fundamentally weakening currency just by splurging their FX reserves.

It will mean that the Bank of Japan will have to tighten faster, but officials have to try to avoid losing control or let rates shoot up too high due to the impact on government borrowing costs. The most recent comments from the BoJ were that they didn’t want to halt the pace of JGB buying, but a glance at the monetary base signals that there has been a slowdown with Feb’s figure of +2.4% YoY slowing to +1.6% in March. So perhaps this is stealth tapering while trying not to spook the markets.

Carry Trade Conundrum

While we think the yen looks too weak, we have to acknowledge there are strong reasons that currency markets have been betting on further weakness in the short term, and the fundamentally driven weakness over the medium term. The most obvious reason is the interest rate gap between Japan and other advanced economies, particularly the US. There are also other forces such as economic growth in Japan compared to other nations, the balance of payments, the huge amount of yen the central bank has printed since the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy and then an even greater pace since BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s “bazooka” in 2013.

Japan has a lot of foreign currency reserves. Second only to China, and about 50% more than the next biggest holder which is Switzerland. Some is on deposit, but the majority is invested. If they start to sell down their securities portfolio, which is largely US treasuries, that puts upward pressure on US yields. Unfortunately for Japanese currency officials, that would make the carry trade even more attractive.

Impact on stock market

Foreign investors have seen the past few years of strong stock market returns reduced dramatically by the currency weakness. We feel this is one of the reasons that foreigners have not flocked back with the kind of inflows we saw in the early Abenomics years. For them, if they wish to take advantage of the Japanese stock market cheapness and corporate governance reforms, it makes sense for them (especially considering career risks) to hedge the currency. By doing so, their inflows to the market do help drive up stock prices but have a further weakening effect on the yen. If the yen moves to a strengthening phase, hedges may be unwound to a degree, and the coupling of stock market returns and yen strength could attract significant unhedged inflows to the Japanese market from foreigners. So, at some point we could see a situation where a strong yen is seen as good for the market, as we believe to be the case from here.

All sources Bloomberg unless otherwise stated.

With contributions from Albert Chu, a portfolio manager focusing on natural resource strategies at Man Group and Adrian Edwards, a portfolio manager on the Japan Core Alpha team.

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.