2020 was a bad year for Value, but even worse for Quality; and as credit creation slows, China attempts to weaken the yuan.

2020 was a bad year for Value, but even worse for Quality; and as credit creation slows, China attempts to weaken the yuan.

January 26 2021

Value Bad, Quality Worse

The underperformance of Value has been a long-term lament within the asset management industry, and 2020 proved no exception. Indeed, by some measures, 2020 could be regarded as the nadir.

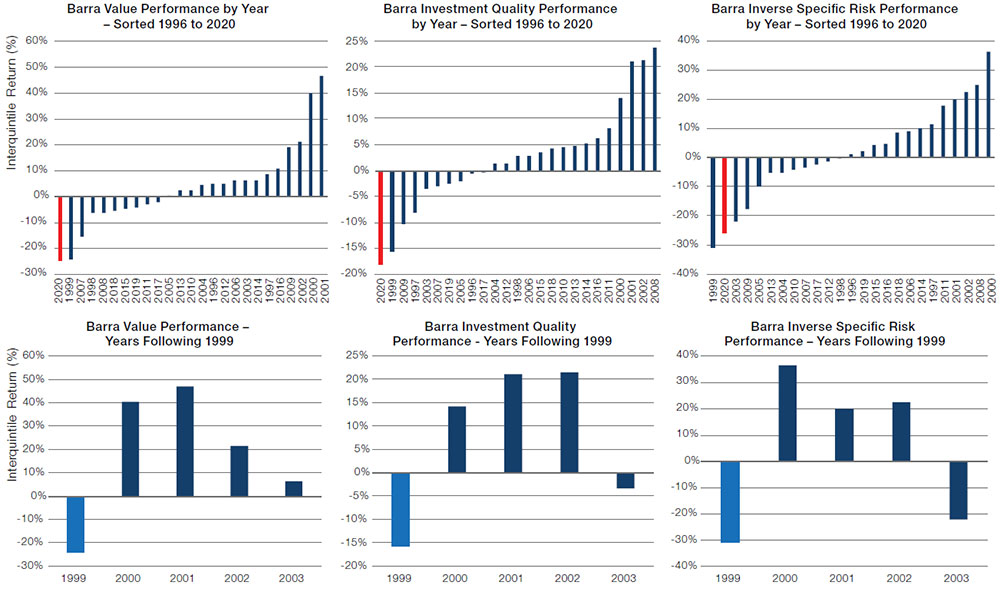

Figure 1 shows the returns to Value, Quality and Specific Risk (inverse) as Barra factors during 2020. This last year was rivalled only by 1999, the peak of the dot-com bubble, for the underperformance of all three factors. Fortunately for Value investors, if a similar returns pattern holds true, the next few years may bring some relief – all three factors saw positive returns for the three years after the bubble broke.

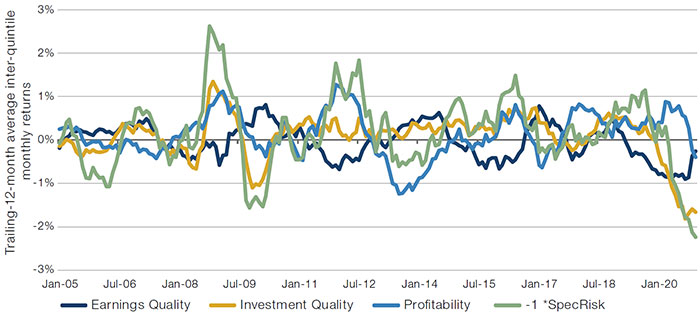

What is even more striking is the poor 2020 performance of Quality in particular. Figure 2 shows the returns to three separate Barra Quality factors and inverse Specific Risk – with the latter and Investment Quality as negative as they have ever been.

Figure 1. Barra Value, Investment Quality and Specific Risk (Inverse)

Source: Man Numeric, as of 31 December 2020.

Figure 2. Rolling 12-month Average Monthly Returns to Three Barra Quality Factors and Negative Specific Risk

Source: Man Numeric, as of 31 December 2020.

A Weakening Yuan?

The official reference rate of the Chinese yuan is fixed versus the US dollar at around 4pm every day in Shanghai by the China Foreign Exchange Trade System, run by the People’s Bank of China. This rate tends to fluctuate in a small range (measured in pips) versus estimates that are published every day. It’s notable that since November, the surprises have tended to be to the weak side, and that on 13 January, the Chinese yuan fixed 95 pips weaker than the estimate, c. 15 basis points.

On its own, this does not look very meaningful. However, it has coincided with macroprudential warnings from the PBoC to Chinese financial companies to limit foreign funding. Together, these signals look like the PBoC may be becoming less comfortable with the strength of the Chinese yuan.

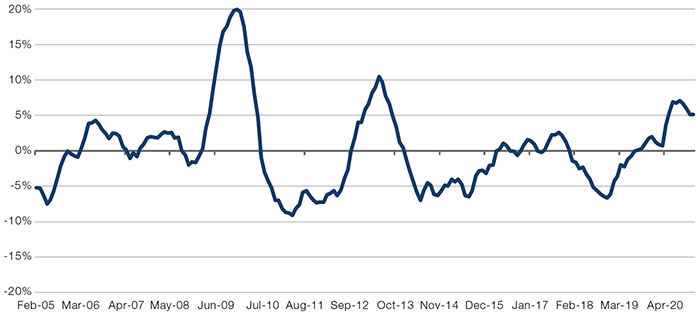

Since late summer, we have observed that the credit impulse in China has been slowing after the stimulus following the onset of the pandemic (Figure 3). Greater credit provision has fed through to the recovery in infrastructure and property investment. However, leaning on this channel – with the accompanying concerns about leverage – is less pressing now that the economy has normalised, hence the willingness to reduce policy accommodation.

It’s possible that the soft signals from the PBoC about the currency are intended to provide a cushion to the economy as it navigates a soft patch between the peak of credit-driven activity and the recovery of the consumer. The extent to which this soft patch matters to the world depends on the extent to which US fiscal stimulus and the consumer recovery feed into China and other emerging markets.

Figure 3. China Credit Impulse

Source: Man GLG; as of November 2020.

With contribution from: Jayendran Rajamony (Man Numeric, Head of Alternatives), Dan Taylor (Man Numeric, CIO) and Ed Cole (Man GLG, Managing Director – Equities).

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.