In this week’s edition: why we believe the US dollar is set to weaken; and what does this mean for emerging-market equities?

In this week’s edition: why we believe the US dollar is set to weaken; and what does this mean for emerging-market equities?

May 26 2020

Quote of the Week:

"China's decision to eschew a GDP growth target rightly de-emphasises growth at all costs and shifts the emphasis to the quality and sustainability of growth."

Trade Up, Dollar Down?

When investors are scared, they turn to the US dollar. It’s not surprising, then, that the coronacrisis has fuelled the greenback towards highs. However, we believe that we are seeing conditions for a weaker dollar slotting into place.

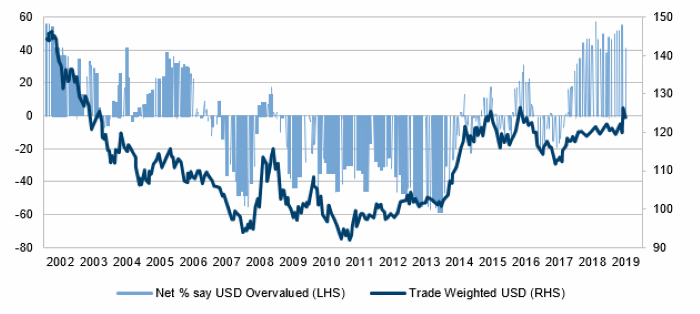

First, investors believe the US dollar is rich. About 40% of respondents to the Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s most recent survey said that they believed the US dollar was overvalued (Figure 1). Normally, these surveys provide interesting contrarian perspectives, but in the case of the value of the dollar, survey responses have been quite accurate.

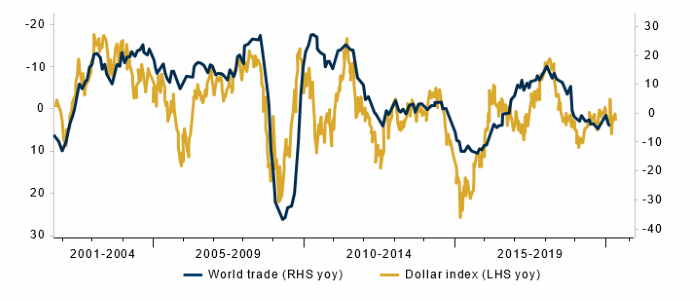

Secondly, there appears to be a correlation between an increase in trade flows and a weakening of the US dollar (Figure 2). As the global economy starts to emerge from the lockdown, we would expect trade flows to accelerate, which has historically coincided with a weaker US dollar as the US consumer purchases goods from around the world.

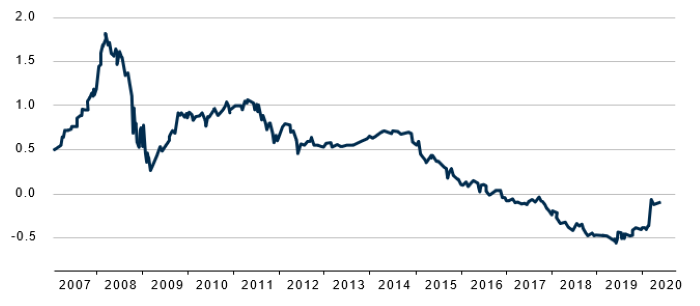

Third, the interest rate pick-up for the US dollar has disappeared. Figure 3 shows a time series of the cost of carry of low-yielding currencies versus the greenback. Before 2013, when much of the developed world started to embark negative policy rates, it consistently cost about 50-100 basis points to hedge the US dollar versus low-yielding currencies. With the onset of negative interest rates, the costs came down. Indeed, from 2016 onwards, you got paid to be long the US dollar versus other low-yielding currencies. And with the Federal Reserve having slashed interest rates in the past three months, it doesn’t pay to be long the US dollar.

We would emphasise, the interest rate differential on its own is not enough: for a weaker US dollar, we need a recovery in trade too.

Figure 1. Survey Respondents Think USD Is Rich

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Fund Manager Survey; as of May 2020.

Figure 2. Correlation Between Trade Flows and USD

Source: Bloomberg; as of 19 May 2020.

Figure 3. The Interest Rate Pick-up for the USD Has Disappeared

Source: Bloomberg; as of 19 May 2020.

Is Now the Time for EM Equity?

If (and it remains an if) we do see a weaker US dollar, this could result in a material loosening of financial conditions in emerging markets (‘EM’), which could benefit equities. In addition, we believe EM equities are looking favourable based on two (somewhat arbitrary, we will admit) clustering models.

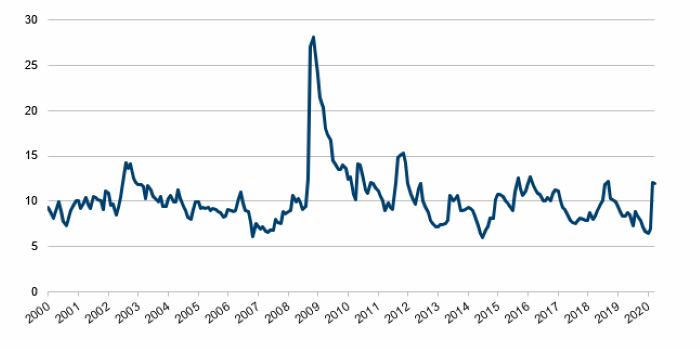

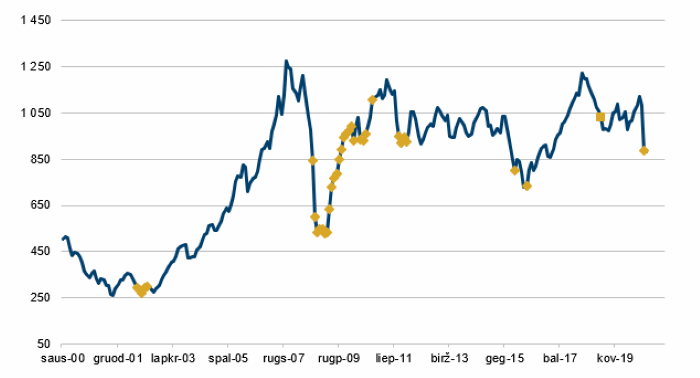

First is EM FX implied vol, which has just hit 12% (Figure 4). The yellow dots in Figure 5 show when EM FX implied vol hits a trigger level of 12% on the MSCI EM Index since 2000. Historically, our analysis shows that buying EM equities when EM FX implied vol hit 12% pays off, with a hit rate of 97% and an average 1-year gain of 32%.

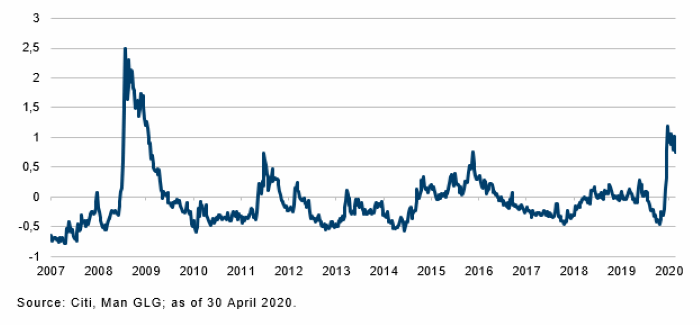

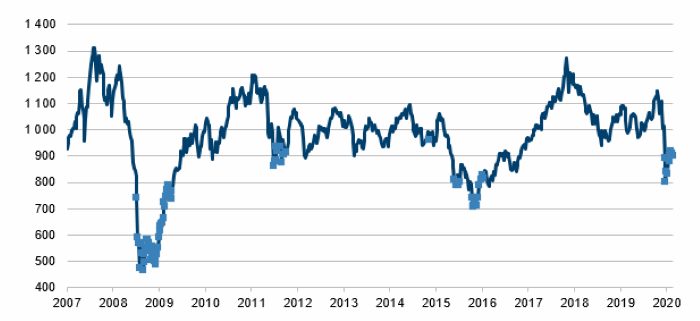

Secondly, we looked at the Citi EM risk index (Figure 6), which shows cross-asset vol by various measures expressed in a standardised form. The blue dots in Figure 7 show when the Citi EM risk index hits a trigger level of 0.5 on the MSCI EM Index. Historically, buying EM equities when the Citi EM risk index has hit 0.5 has paid off well, with a hit rate of 100% and an average 1-year gain of 62%.

Figure 4. EM FX Implied Vol

Source: Bloomberg, Man GLG; as of 30 April 2020.

Figure 5. MSCI EM With Vol-Based Buy Triggers

Source: Bloomberg, Man GLG; as of 30 April 2020.

Figure 6. Citi EM Risk Index

Source: Citi, Man GLG; as of 30 April 2020.

Figure 7. MSCI EM With Citi Index-Based Buy Triggers

Source: Bloomberg, Man GLG; as of 30 April 2020.

We're Not Alone

The unprecedented fiscal response to coronavirus from governments and central banks has done its job, in the short term at least. Equity markets have rallied, credit spreads have stabilised, and the wave of defaults many feared would overwhelm the economy has been kept at bay by various emergency lending programmes.

But where does this lead us? As a firm, we’ve collectively been discussing coronavirus and its

inflationary implications for some time: expanding central bank balance sheets and fiscal deficits (all sparked by the coronacrisis), and a lack of appetite for the austerity that many countries engaged in after the Global Financial Crisis may induce governments to inflate away their debt by keeping rates low and spending high. Indeed, even before the onset of the coronacrisis, inflation has been an important part of our investment thinking.

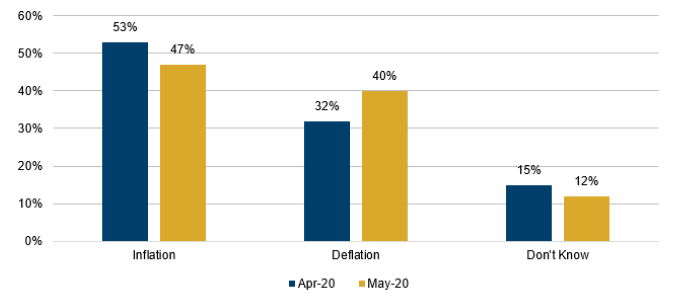

But now it appears that we are not alone. Almost half of 450 respondents to a Deutsche Bank survey (Figure 8) said they believed the coronacrisis will precipitate inflation over a 1- to 5-year timeframe. In contrast, only 40% felt that it will be deflationary over the medium term.

Figure 8. Survey Says…

Source: Deutsche Bank; as of May 2020.

Investors were asked: Do you think we are more likely to see inflation or deflation in 1-5 years due to coronavirus?

With contribution from: Ed Cole (Man GLG, Managing Director – Equities) and Teun Draaisma (Man Solutions, Portfolio Manager).

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.