In this week’s edition: what next in the Brexit saga?; and the US jobs statistic that hasn’t been seen this century.

In this week’s edition: what next in the Brexit saga?; and the US jobs statistic that hasn’t been seen this century.

March 19 2019

Brexit – What Happens Next?

It has been an action-packed week in Westminster, with a series of votes taking place to determine what exactly parliament wants from Brexit. The answer still appears to be… nobody knows.

The second ‘meaningful vote’ was held on 12 March as promised – unsurprisingly, the UK government was, once again, defeated. UK Prime Minister Theresa May kept to her promise of further votes on the prospect of no-deal and an extension. Parliament took control of the UK government’s no-deal motion and on 13 March voted to avoid a no-deal in any scenario. The following day, it voted with the government for either a short extension and her deal, or a longer extension.

May seemed to miss an opportunity following the no-deal vote that would have allowed her to take back control of the process, in our view. Rather than allow the vote on an extension – where May has no control over what amendments will be voted on – she could have announced that there would be an extension. This would have put the UK government back in control of any extension request in particular on how long it would be for. May has now reverted to her main strategy of trying to scare the Eurosceptic members of her party into backing her deal out of fear of the ‘risk’ of a softer Brexit or no Brexit at all. These members are being given a third opportunity to fall in line with a third ‘meaningful vote’ expected in advance of the EU summit on 20-21 March.

Whilst it remains unclear whether the fear tactics being used by May will secure enough votes to pass the deal, we believe that depending on the result of this vote, there will be one of the following two outcomes:

- May’s deal is passed: In this event, May will apply for a short extension that will end before the European Parliament elections. The extension will be a technical one to allow the terms of the deal to be implemented. We feel the EU would agree to this extension – remember, all 27 member states have to unanimously agree on an extension.

- May’s deal is defeated: Here, the path forward is more hazardous. May would have to petition the EU for a significantly longer extension – possibly up to two years. This will anger the Eurosceptic members of the Conservative party. However, the main issue is whether or not the EU would agree to this – and if they do, what terms and conditions would be applied. This would mean that the UK would have to elect MEPs to the European Parliament (historically, the UK has tended to elect anti-EU MEPs) and the EU may also ask for a reason for this extension – i.e. what will the UK do with this time – a question that has yet to be answered. If all 27 members of the EU do not agree to this extension, there is a very real risk of a no-deal Brexit occurring, despite Parliament’s opposition to it. The only other option at that point that would remain would be, well, to remain.

Up, Up, Maybe Away

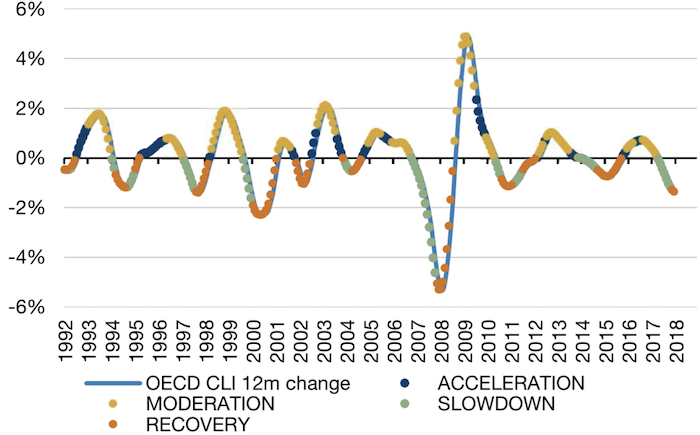

The OECD’s leading indicator series, designed to anticipate economic turning points 6-9 months ahead, is now in its second month of ‘recovery’ (according to our own definition of cycles), based on January data. Broadly speaking, the January data was sequentially better, with second derivative improvements in all regions except Germany and Japan.

Typically, 12-month forward returns after the second month of the recovery phase have historically proven to be positive, with value outperforming. Indeed, 2001 was the only signal that failed as the dotcom bubble deflated.

Figure 1: January – the Second Month of ‘Recovery’

As of 31 January, 2019

Labour Isn’t Working?

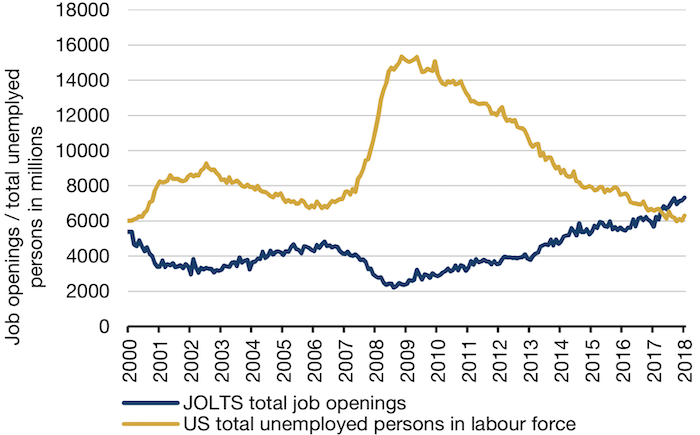

The strength of the US economy is highlighted by an interesting statistic. Total jobs openings (as calculated by JOLTS) were at 7.3 million as of 1 January, 2019. This compares with just 6.3 million unemployed persons in the labour force, leaving 1.2 job openings for each jobseeker.

This discrepancy first arose last year but previously had not been seen this century (Figure 2). Is this a good or a bad thing for the US economy? Two competing narratives have emerged. It could be that we are still at the top of the cycle with an economy moving so quickly that the labour market can’t keep up. Then again, it could also be that the US labour force is not qualified for the roles that the modern economy demands.

Figure 2: US Jobseekers Versus Job Openings

As of 1 January, 2019

With contribution from: Man FRM OpRisk, Ben Funnell (Man Solutions, Portfolio Manager), Teun Draaisma (Man Solutions, Portfolio Manager), Henry Neville (Man Solutions, Analyst) and Ed Cole (Man GLG, Managing Director).

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.