While trade wars have been the story of the last few months, we believe that the tail risks – rather than either the US or China – lies in Europe, particularly within the banking sector.

While trade wars have been the story of the last few months, we believe that the tail risks – rather than either the US or China – lies in Europe, particularly within the banking sector.

July 2019

Introduction

Trade wars have been the story of the last few months. Not content with fighting a trade war with China, US President Donald Trump has opened up a second front by promptly demanding trade concessions, not only from Mexico, but also India and the European Union.

Markets have been focused on developments on the trade-war front. The S&P 500 Index closed at a record high on 2 July, following positive soundbites from the meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping at the G20 summit.1 Still, the conflict between the US and China, and indeed, between the US and Mexico or India or the EU, is unresolved. Indeed, a June survey by Bank of America Merrill Lynch showed that 56% of money managers said trade wars were the top tail risk.2

In our view, however, the real problem typically lies outside the main participants. And in this case, we believe that the tail risks – rather than either the US or China – lies in Europe, and in particular, within the European banking sector.

The Charts to Watch

Our anxiety with the European banking sector can be illustrated with three charts.

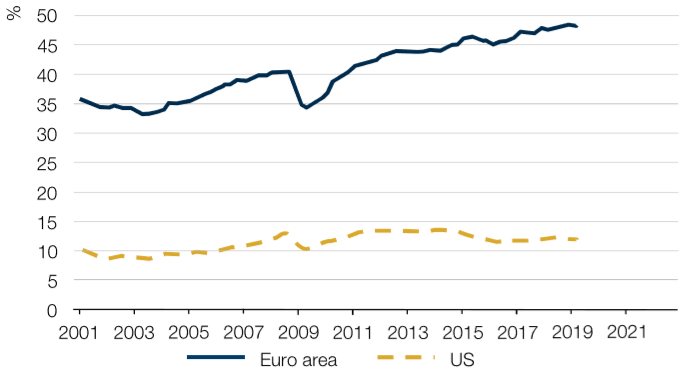

Much of the analysis of the effects of the trade war has focused on estimating the impact of tariffs on the economies of the US and China. Less coverage has been given to the effects of the trade war on the rest of the world. In particular, exports account for almost 50% of GDP in Europe, compared with about 15% for the US (Figure 1). For China, exports account for about 20% of GDP.3

Figure 1. Exports as a Percentage of GDP

Source: BCA Research, as of June 2019.

A trade war has already resulted in a sharp slowdown of European exports, particularly affecting the German economy, as shown by the most recent manufacturing PMI. This has already triggered a reaction by the European Central Bank, which said it could reduce interest rates and start a second wave of quantitative easing (‘QE’). Since 2008, low (and negative) interest rates, and QE, have provided European corporates with easy financing and assisted credit creation. Whilst this has been positive for asset prices and credit spreads, the reverse has been true for banks’ profitability.

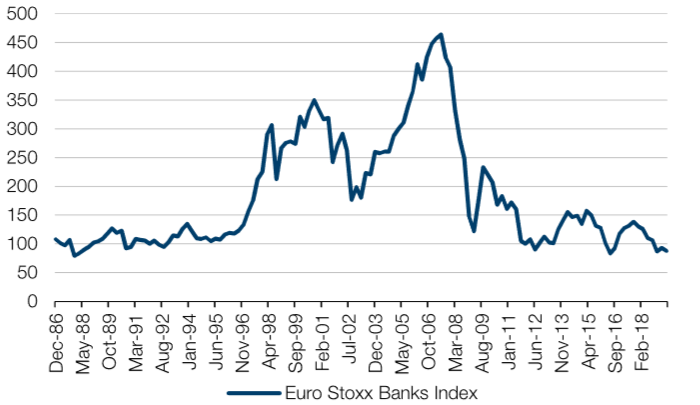

This brings us to our second chart, which shows how the Euro Stoxx Banks Index has collapsed since 2008. ECB President Mario Draghi has insisted that “low profitability is not an inevitable consequence of negative rates”.4 However, the market appears to disagree: the index is close to breaking through a number of multi-decade technical support levels (Figure 2), and has been in the doldrums since the ECB started its rate cutting cycle in 2008.

Figure 2. Euro Stoxx Banks Index Breaching Multi-Decade Technical Support Levels

Source: Bloomberg, as of 28 June 2019.

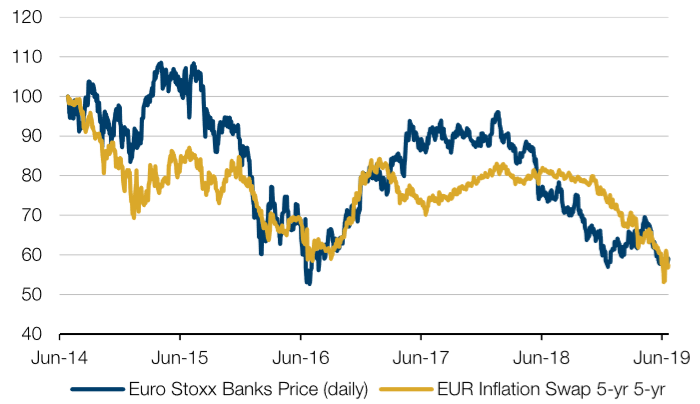

Our third chart is the 5-year, 5-year inflation rate, a measure of expected inflation over a 5-year period beginning in five years’ time. In our opinion, it is a good barometer of the success of monetary policy in terms of meeting the ECB’s stated inflation target of “close to but below 2%”.5 The decline in the 5-year, 5-year inflation rate indicates that the market no longer believes that dovish central bank policy will have its intended effect and restore demand and inflation. Essentially, the market is telling the ECB that it is behind the curve and will not meet its inflation target.

This precipitated a verbal response from the ECB; Draghi’s comments that additional stimulus, further QE and interest cuts remain part of the ECB’s arsenal were effectively an attempt to demonstrate that the ECB still has tools to tackle a crisis.6

Figure 3. Euro Stocks Banks Index Versus EUR Inflation Swap 5-Year 5-Year

Source: Bloomberg, as of 28 June 2019. Normalised to 100 on 30 June, 2014.

Interest-rate cuts are effective in stimulating the economy because they bring future consumption forward in time. As borrowing is cheaper, firms and individuals make purchases in the present that they would otherwise delay, to take advantage of easier credit conditions. However, a secondary effect of this is that future demand is depleted: purchases – which would have been made in the future – have been brought forward. What Figure 3 shows is that the market believes that a great deal of future consumption has already happened; there is little room for more consumption to be brought forward. This is effectively sending the message that further rate cuts would have a limited impact on consumption as a great deal of future consumption has been brought forward through interest-rate cuts.

In addition, for interest-rate cuts to be effective, the ‘pass-through’ rate from banks has to be high. No-one in the real economy borrows from the central bank; instead, they rely on banks to pass their own low borrowing rates on to customers. Research by Goldman Sachs7 shows that the pass-through has declined “significantly” since the ECB’s deposit facility rate went negative in June 2014, suggesting that while further rate cuts might lower lending rates somewhat more, they are more likely to weigh on bank interest margins.

So, What Can Be Done?

How to react to this Jeremiad? We believe that a joint approach is needed: banks need help from policymakers, but also need to help themselves.

One possible solution is a combination of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (‘TLTRO’) and tiering. As we explained in January 2017, one side-effect of QE in Europe has been to drain cash out of the southern European banking system into the northern one. The ECB’s previous TLTRO program was effective in providing cheap capital to southern European banks, in our view. Indeed, a new program with similar features has been announced, which – along with a 10 basis points rate cut from the ECB – should be effective from September. This addresses one of the main problems in Eurozone banking: the relative lack of capital in southern Europe due to continuing balance sheet clean-up, which has hindered growth. On the other hand, tiering would mean the northern European banks, awash with cash, would not have to pay to hold excess cash at the ECB. We believe the overall impact of tiering on the sector is likely to offset any increase in rate cuts (into negative territory) from the ECB. Indeed, analysis by Autonomous Research shows that tiering would offset the impact of the 10bp rate cut, equivalent to about 2% of pre-tax profits.8

The second option is restructuring. As the breakdown of the Deutsche Bank/Commerzbank merger talks demonstrate, no one wants to pay to buy a poorly performing competitor, and mergers are fraught with the risk of picking up another bank’s underperforming assets. One possible restructuring route could be the creation of a ‘bad bank’, selling off the poorly performing units of banks to leave a smaller, more efficient business behind. Indeed, Deutsche Bank has indicated that it will be creating a bad bank and close units which don’t meet the cost of capital.

A possible third solution would be a move toward a ‘real’ European banking union. What do we mean by this? At the moment, there are two drawbacks to the ‘partial’ banking union that currently exists in Europe: First, a bank headquartered in one European jurisdiction cannot, and is not permitted to, move excess liquidity or capital from one jurisdiction to another. Secondly, there is no playbook about what M&A means for capital; as an example, there is no clear guidance on the capital requirements if a bank in one jurisdiction wants to buy a competitor in another jurisdiction. A ‘real’ European banking union – where movement of liquidity and capital is unhindered; and there are clear-cut guidelines on what happens in events such as M&A – should help European banks to cut further cost via synergies.

Conclusion

Geopolitics, and in particular trade wars, are a concern. However, history has shown us that it’s prudent to not just focus on the main issue at hand, but also on the periphery; in this case, European banks. Inflation and the current interest-rate cycle may be condemning European banking to the doldrums for the foreseeable future. However, there are three steps that may be taken to help European banks: tiering, restructuring and the formation of a ‘real’ banking union. We believe these are necessary steps, not just to reduce tail-risks for Europe, but also for the rest of the world.

1. Source: Bloomberg.

3. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com

5. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/strategy/pricestab/html/index.en.html

7. Soeren Radde, Sven Jari Stehn; How Much Could the ECB Cut?; Goldman Sachs; 16 June 2019

8. Corinne Cunningham; ECB: Germany Holds the Key; Autonomous Research; 22 July 2019

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.