Despite equity euphoria, investors need to keep a weather eye on the big risk – inflation – and tilt their portfolios to match. In our view, this means seeking out the relative value available in the UK, Europe and Asia.

Despite equity euphoria, investors need to keep a weather eye on the big risk – inflation – and tilt their portfolios to match. In our view, this means seeking out the relative value available in the UK, Europe and Asia.

February 2021

Introduction: Long-Term Risks

The joke doing the rounds in London is that the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England has had a name change – it is now the Magic Money Tree Committee. And it is not just the UK. In our view, the coronavirus pandemic has homogenised one aspect of all markets: governments and corporations everywhere have tapped credit markets to stave off the effects of the downturn, increasing the global debt burden in a relatively uniform manner. This massive global debt will be a significant drag on growth and earnings for years to come.

While this borrowing was necessary to keep the global economy afloat as governments decided to shut down large parts of entire economies, it brings us straight back to our major risk: inflation. Until now, policymakers have been able to deploy massive amounts of quantitative easing (‘QE’) without worrying about sparking inflation. But the pandemic has seen the first signs of concerted monetary and fiscal stimulus. If electorates come to believe that this is the normal state of affairs, this will cause a major shift in the political environment, with calls for higher spending and continued high levels of government borrowing. The siren song of Modern Monetary Theory will continue to sound as long as interest rates stay low, and since low rates are a function of low inflation, we are right back to our primary concern. But what concerns us most is that our entire financial system is reliant on continued low rates, leading to a massive asymmetry of risk. If deflation continues, then we simply get more of the same. If, on the other hand, loose fiscal policy does trigger inflation and increase the cost of servicing global debt, the effect would be worse by orders of magnitude.

Last year, we outlined the potential for a coming inflationary storm over the next decade – and with it, the possible consequences of a regime rotation between Value and Growth. This risk is still real: the US 2-year inflation breakeven is now at 2.5% (Figure 1) while the 5-year 5-year inflation swap rate is standing at 2.1%. More than the absolute level, the pace of increase is rising quickly, with a 50 basis points increase in the 2-year breakeven since the announcement of the vaccine. With the US 10-year remaining steady, real yields have fallen, driving asset prices from Bitcoin to equities towards new highs. Another spike has been observed in agricultural commodities, which makes it likely that inflation will be felt directly in food prices – which itself has implications for social welfare (Figure 2). If reflationary forces become too powerful, we should expect a violent correction. Over the long term, a move to a new inflationary regime would be volatile.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 11 February 2021.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 11 February 2021.

To give a framework of how this could play out, it may be useful to think about regime change in terms of Elliott Wave theory, a behavioral finance model which posits that cycles in markets move in five waves. In this case, the first inflationary wave tends to be unheralded (which would be unsurprising given how long the opposite regime has persisted for). The impact of the inflationary wave would potentially put pressure on the valuation of assets, especially bonds, equities and real estate, causing a selloff. This selloff would create a counter-trend, massive deflationary shock which would stop the first wave dead in its tracks.

The market tends to regard the second wave as confirming their previous mindset – a case of “I told you so, there is no way inflation can occur.” This wave could trigger another powerful response from central banks, unleashing the full range of monetary and fiscal tools that we have seen on display in the last decade. This would set the stage for the third wave, again inflationary, when market participants realise regime change is coming, and panic. The fourth wave is another deflationary counter-trend, and is often a messy one, as market participants hesitate to embrace the new regime, caught between the deflationary shock and the inflation of wave three. The fifth is the consensus wave, with investors accepting and adapting to the new environment.

Euphoria and Short-Term Risk

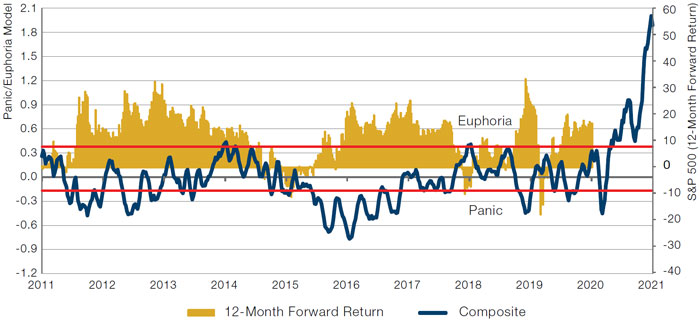

Despite the risks to the downside, equity markets are firmly in a euphoric phase, particularly in the US (Figure 3). A powerful illustration of this euphoria is the recent relative performance of non-profitable Nasdaq companies versus the broader index (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Panic/Euphoria Model – US Equities

Source: Citi, Haver Analytics, Pinnacle; as of 21 January 2021.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg, Goldman Sachs; as of 5 February 2021.

Normalised to 100 on 12 September 2014.

In our view, this euphoria may well continue. While the pandemic is still spreading, the rollout of a vaccine offers hope that 2021 will be a much more normal year. Indeed, the vaccine is a unique economic stimulus in that it significantly eases supply conditions at the same time as stimulating demand. Overall this should help cyclical and Value stocks over the rest of the market – in particular, the Growth ‘concept’ stocks that have fuelled a large part of the recent euphoria.

In addition, sources of volatility have been taken off the table at the same time as fiscal stimulus has arrived. Fears that former President Donald Trump would be able to impede a transfer of power have been unfounded. Market participants quickly understood that Trump would be unable to overturn the election, and have brushed aside the noise produced by the invasion of the Capitol by the mob. After the Georgia Senate runoff, Democratic control of the Presidency, the House of Representatives and the Senate means that there will be very little obstruction of renewed fiscal stimulus. Despite the wilder grumbling about the election, the desire of both parties to deliver an economic recovery was underlined by the announcement of an increase in the December Coronavirus Stimulus Bill by Congress, which provides individual Americans with stimulus cheques of USD2,000. In addition, President Biden has promised a further USD1.9 trillion of stimulus.1

If market euphoria has been founded on the belief that the election of President Biden will herald continued stimulus, his appointments have only served to reinforce it. Former Chair of the Federal Reserve Janet Yellen has been appointed Treasury Secretary, thus ensuring that a key office will be occupied by a relatively dovish former Fed Chair. In her confirmation hearing, Yellen argued that “with interest rates at historic lows, the smartest thing we can do is act big” and also that she saw interest rates staying low for “a long time”. This is eerily reminiscent of Alan Greenspan’s justification of the level of the US stock market before the dotcom bubble burst, when he argued that productivity growth should remain very high for a long time. While the Fed is independent within the government, we now have a combination of a dovish current Fed Chair in Jerome Powell, a dovish Treasury Secretary in Yellen and a President committed opening the fiscal floodgates. In short, the entire American executive is in harness and pulling hard in the same direction – and expecting to do so for the long term.

Such conditions make the current euphoria understandable, with stimulus set to arrive just as real rates are falling. However, these conditions are unlikely to last forever, and provide an overextended environment in which to deploy capital. Such euphoria leaves markets vulnerable to corrections – a huge amount of good news has already been priced in, and realistically, it is hard to see how the news flow can become much more accommodative. In the short term, there is a huge amount of risk to the downside as well.

Where Do We Put Our Money?

While we are waiting for this inflation regime change, doing nothing is not an option, for two reasons. Firstly, assets have to be managed. Portfolios cannot simply be converted to cash. Less prosaically, being early is often as bad, if not worse, than being wrong. Managers must do something with their money, and until we see concerted signs of inflation, it is risky to bet the house on regime change.

Simply riding the upward trend of US equities becomes problematic when we consider what might happen if our inflation argument is wrong. At least some of the thinking behind the current US equity euphoria is that US equities are cheap versus bonds. However, we should consider the example of Japan when thinking about what happens in a deflation environment when stocks are cheap relative to bonds. Japan has been battling deflation for the last 30 years, and over that time period has seen limited equity returns.

While US equities will tend to dominate the global equity story, the S&P 500 Index is trading on a forward price-to-earnings (‘PE’) ratio of around 23 times, and is already expensive when compared with the rest of the world (Figure 5). Furthermore, the US equity risk premium remains lower than other regions (Figure 6). If equity risk premiums are high, investors demand a higher premium to hold risk assets, increasing the required rate of return which in turn reduces the present value of future cashflows and is reflected in lower equity prices. If the US equity risk premium is low compared with its peers, it therefore makes the price of US equities relatively expensive.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 11 February 2021.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Goldman Sachs Research; as of 19 January 2021.

Implied ERPs are calculated by each regional strategy team. While specific assumptions differ between regions, all are calculated using similar frameworks.

In this environment, we believe opportunities lie in relative value. While everyone has borrowed, not all equity markets are the same. Some regions are more equal than others when it comes to recovering from the effects of the pandemic. There are wide disparities in valuation between regions, and we believe it is these disparities that investors should focus on to mitigate at least some of the risks posed to equity owners. At an index level, UK and European equities trade relatively cheaply compared with US equities, while Asian equities trade at a significant discount.

In our view, managers should take some risk exposure, but must do as selectively as possible, mindful that the party may be ended by an inflation breakout. However, blindly allocating on a regional basis is a recipe for disaster. Instead, regional disparities should be seen as a stock-picker’s market, where active management can come into its own. By being selective and finding the stocks which can outperform their region’s trends, investors can flex portfolios, selecting stocks which fit well with market trends, yet have good enough fundamentals to justify their price.

Europe and the UK

The MSCI Europe ex-UK Index is trading at around 18x PE, a reasonable discount to the US, while the FTSE All-Share Index is even cheaper at around 15x (Figures 7-8).

Figure 7. MSCI Europe ex-UK Forward PE Ratio

Source: Bloomberg; as of 11 February 2021.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 11 February 2021.

Why is the UK trading so cheaply? Brexit has been an ongoing challenge, causing investors to eschew UK stocks for fear that the country’s trade flows and economic growth will be badly affected by the decision to leave the EU. As such, UK equities are trading at a deep discount, a discount which has filtered through to continental equities to some extent. Concerns in this area have now been answered: the new UK/EU trade deal offers a ‘no tariffs, no quotas’ trading relationship and puts relations between the two powers on a stable, permanent footing. As we expected, the trade deal is relatively thin, only covering manufacturing, not services. While this is less comprehensive than the UK’s previous membership of the Single Market, the UK has finally checked out of the 4-year twilight zone which characterised its trade arrangements during the negotiation period. As a consequence, we have seen a bounce in UK equities, but this has not been large enough to completely erase the PE discount compared with the US. Despite some minor disruption observed in early January as both parties adapted to the new requirements, UK equities may still have the conditions and momentum which could see a further re-rating. The country has one of the best vaccination rates globally, which may well speed its recovery compared with peers. With such positive momentum, and a discount on a PE basis, UK equities may be one of the best global hedges against an inflation breakout, in our view.

At around 21x PE, European equities (as represented by the Euro Stoxx 600 Index) again offers relative value versus the US, despite being expensive in absolute terms and versus history (Figure 9). However, there are other wider factors which weigh on European equities: the perceived regulatory burden of the EU Single Market is often posited as an unnecessary burden placed on the continent’s businesses. The recent abrupt decision by the French government to block the takeover of Carrefour by the Canadian Couche-Tard highlights the risk of constant intervention by European governments in private company matters. Counter-intuitively, such a hostile environment means that any company that can thrive is uniquely strong.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 11 February 2021.

If investors are prepared to jettison their view of the continent’s equity markets as a collection of old economy stocks, they may find their rewards. While Europe is not Silicon Valley, there are enough firms who are leaders in the shift to online and resilient enough to cope with the regulatory burden to allow stock pickers to benefit from the gap between perception and reality. Additionally, the end of the Brexit negotiations offers both the UK and European stocks a catalyst to re-rate. All in all, if managers focus on the very best companies, they could well see conditions for relatively strong equity returns.

Asia

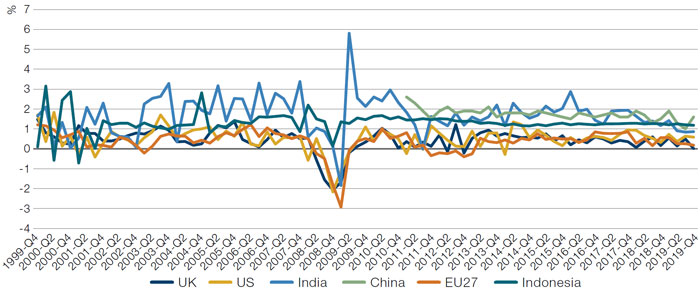

Asian equities provide an even larger margin of safety from a valuation perspective, with the MSCI Asia ex-Japan Index trading at c18x PE (Figure 10). Furthermore, those regimes which have seen the lowest instances of coronavirus spread have been concentrated in Asia, and the continent enjoys higher GDP growth rates than Europe and the US (Figure 11). While the vaccine will provide less delta in its boost to economic activity in Asia than those regions that have been hit worst, the export-led nature of many Asian economies does stand to benefit significantly from improving demand in the Western world. Asian equities are therefore likely to be able to provide strong returns. It is also worth mentioning that there are second derivative plays on the Asian story such as Brazil which combines very attractive valuation (the Bovespa trades at 12x PE) with a commodities-based exposure to a post-pandemic global cyclical recovery.

Problems loading this infographic? - Please click here

Source: Bloomberg; as of 11 February 2021.

However, caution is still required. While one could expect beta to deliver the required results, many Asian markets suffer from the opposite regulatory problem to the EU and the US: a higher number of fraudulent companies than the norm. Frequent accounting fraud scandals mean that active management is a key factor in managing market risk: diligent, bottom-up research is all the more valuable in a region where investors protections may be less stringent, and accounting standards more varied. In our view, investors should therefore engage with caution, and maintain an active approach. The recent withdrawal of the Ant IPO is evidence of how beta alone is unlikely to provide returns without a level of downside risk. If we add in the risk posed by the domination of Chinese equity indices by very large tech companies, we may actually looking at an environment where returns to the index are capped, even as individual stocks perform well.

Figure 11. OECD GDP Growth Rates 2000-2019 – US, EU, UK, China, Indonesia, India

Source: Bloomberg; as of 31 December 2020.

This is not to suggest that one should avoid Asian equities. On the contrary, the region offers many dynamic firms and the opportunity for equity investors to ride a positive growth trend. But in such a troubled regulatory environment, there is money to made on the short side as well as the long. Active management is therefore required to make the most of the obvious opportunity in Asian equities.

Conclusion

With any luck, 2021 will be a more cheerful year than 2020 – indeed, it would be hard pushed to be much worse. The US equity market is now exceptionally frothy, with all the frustrated ambitions of last year, and hope for the next baked into the price.

However, we believe investors need to look beyond the good news, and instead think hard about how they can best protect themselves in an increasingly indebted world. With an ever-growing temptation for governments to inflate away their debt, we believe equity investors should think in relative terms, prioritising those regions offering relative value and higher growth rates. With no way of knowing when regime change might occur, investors would benefit from building portfolios with one eye on a potential inflationary future.

Within this broad framework, investors are likely to benefit from the risk management offered by active managers, and by being exceptionally selective when it comes to stock picking. For those that want to avoid excessive beta risk, market neutral equity funds could be an option. In our view, the combination of risk versus reward is offered away from the buoyant US: in Europe (in the UK in particular) and Asian equities. Not every fashionable stock is robust enough to cope with regime change. Above all, investors should tread carefully, and keep an eye on the main risk: inflation.

1. Financial Times: Biden to push USD1.9 trillion for battered US economy

You are now exiting our website

Please be aware that you are now exiting the Man Institute | Man Group website. Links to our social media pages are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Man Institute | Man Group has no control over such pages, does not recommend or endorse any opinions or non-Man Institute | Man Group related information or content of such sites and makes no warranties as to their content. Man Institute | Man Group assumes no liability for non Man Institute | Man Group related information contained in social media pages. Please note that the social media sites may have different terms of use, privacy and/or security policy from Man Institute | Man Group.